Detail, Isidore Leroy de Barde, A Selection of Shells Arranged on a Shelf, watercolor and gouache, 1803.

Detail, Isidore Leroy de Barde, A Selection of Shells Arranged on a Shelf, watercolor and gouache, 1803.

Cabinets of Curiosity: the Web as Wunderkammer

We moderns tend to associate boxes and cabinets with the mundane. They hold a single type of item. They order and sort. They serve as metaphors for the banal, the ordinary, the pedestrian. Our public figures frequently endeavor to “think outside” them and occasionally offer to blow them up.

Yet imagine a cabinet that contains rubies, “unicorn” horns, and Hindu sculptures. Pocket watches, pocket portraits, guns, silk ribbons, saints’ relics, and perfume bottles. Deadly poisons, Amazonian drugs, powdered mummies, fossilized bones, and bezoar stones. A cabinet that contains a world in miniature.

This was the curiosity cabinet, or Wunderkammer, one of the defining creations of the tumultous era that historians call the early modern period. The curiosity cabinet’s modeling of the cosmos was no coincidence. The belief in correspondences between the universe and internal systems was in the early modern air. Men and women of that time even envisioned their own bodies as microcosms of creation. And in the age of piracy, East India Companies, slave trading and colonial expansion, the wonders of Creation were often conflated with the treasures of the tropical world—with the exotic.

This correspondence was likely what the English writer and physician Sir Thomas Browne had in his (capacious, highly unusual) mind when he opined that “there is no man alone, because every man is a Microcosm… There is all Africa, and her prodigies in us.” Virginia Woolf, a great admirer of Browne, went so far as to argue that the old doctor’s preoccupation with microcosms “paved the way for all psychological novelists… He it was who first turned from the contacts of men with men to their lonely life within.”

The early modern curiosity cabinet stood at the intersection of this dual preoccupation with internal psychology (microcosms) and the exotic, rare, rich or unfamiliar (the cosmos). By building curiosity cabinets, early modern elites made their mental lives manifest: the curiosity cabinet displayed its owner’s interests, tastes, travels, and “wit,” yet it was also an assemblage of found objects, and thus a display of the external world in all its infinite variety.

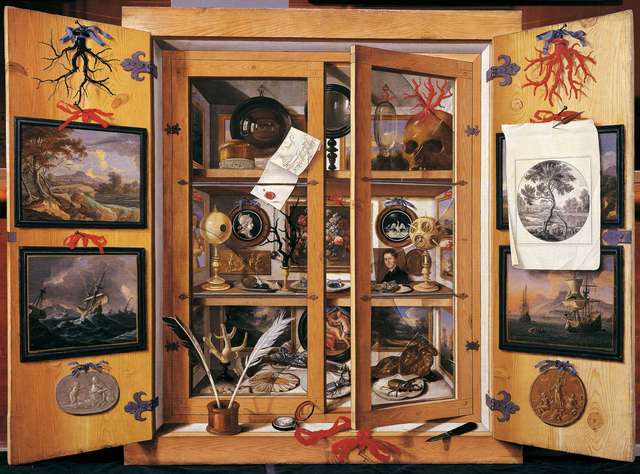

In keeping with the Baroque taste for visual variety, asymmetry, organic forms and the wondrous and monstrous, these cabinets were stuffed to the brim with bizarre and far-flung finds, and their organization often strikes modern eyes as haphazard. Frans Francken’s ingenious painting of a curiosity cabinet, for instance, revels in clutter. Here a scattering of stamps, gems, coins, unguent bottles, oil lamps and a variety of shells contrast with an only slightly more orderly display of paintings-within-paintings, which themselves abut a dried seahorse and tropical fish. One wonders what it all smelled like.

The obscure Venetian painter Domenico Remps’ painting of a curiosity cabinet, created some 40 years after that of Francken, shows how the genre had evolved over the course of the seventeenth century. Remps’ cabinet is purpose-built for display of exotica, and features an elaborate blend of artifacts attesting to an acceleration of long-distance trade (corals, paintings and engravings of sailing vessels) along with objects of art, and items that were (at the time) high technology: optical glasses, a pocket watch, a pistol.

Yet all was not chaos. As Met curator Wolfram Koeppe explains, there was a degree of internal order at work here, a “formula” for Wunderkammeren.

The three ingredients for success in showcasing a collector’s panoramic education and broad humanist learning were naturalia (products of nature), arteficialia (or artefacta, the products of man), and scientifica (the testaments of man’s ability to dominate nature, such as astrolabes, clocks, automatons, and scientific instruments).

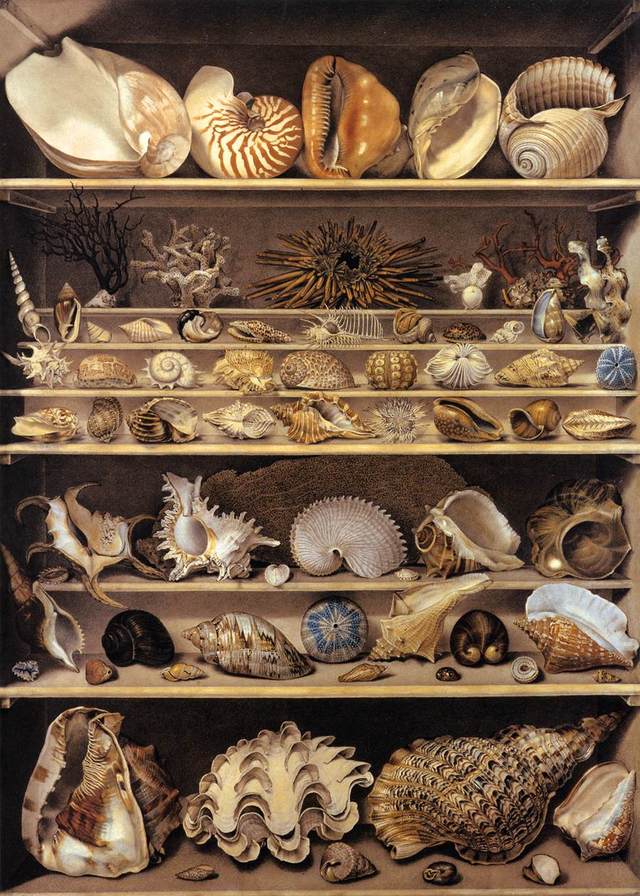

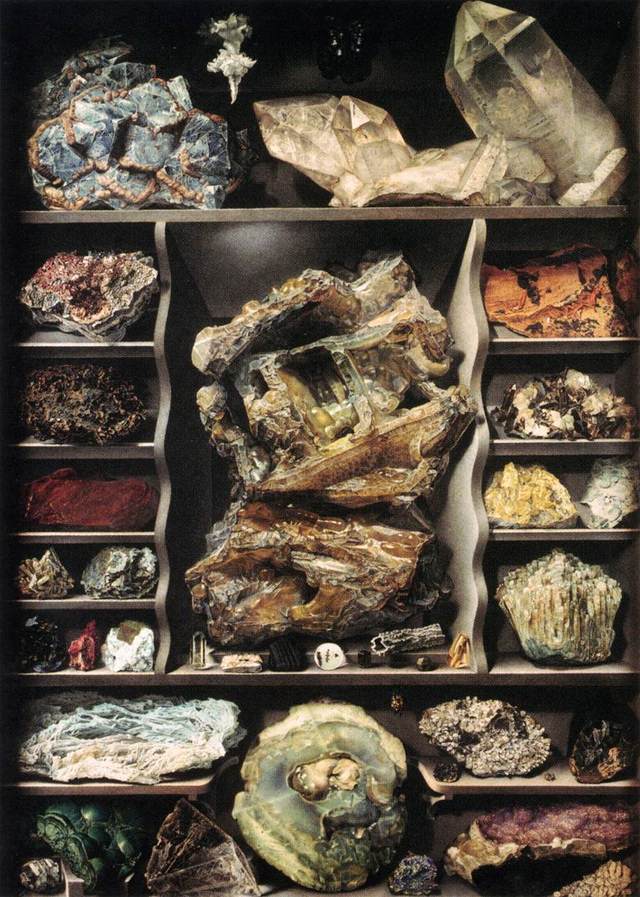

As the loosely-defined Baroque era segued into the more empirically-minded Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, curiosity cabinets became correspondingly more orderly. They borrowed a page from Linnaeus—he of species classification fame—and started to order their objects according to rational classification schemes. Alexandre Isidore Leroy de Barde’s remarkably precise and disciplined watercolors of naturalia cabinets are perfect example of the shift:

Isidore Leroy de Barde, A Selection of Shells Arranged on a Shelf, watercolor and gouache, 1803. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Isidore Leroy de Barde, Minerals in Crystallization, watercolor and gouache, 1813. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yet even these images—more orderly, to be sure—retained a poetic quality. They were not truly scientific; their groupings relied on the collector’s taste and intuition. As science became standardized and institutional, curiosity cabinets fell out of fashion. On the other hand, in the realm of art (following a circuitous path that leads us through Joseph Cornell’s enchanting boxes and Robert Rauschenberg’s combines), the cluttered, fragmented, eclectic aesthetic of the curiosity cabinet carried into the twentieth century.

Yet perhaps the pre-eminent contemporary influence of the Wunderkammer has gone unnoticed.

My thinking here was set in motion when I noticed that by far the most frequently visited post on my blog of early modern history, Res Obscura, has to do with curiosity cabinets. Why the intense interest in what I had always thought of as one of the more arcane, if appealing, sidelights of the early modern era, like the equally Baroque works of Athanasius Kircher?

Reflecting on this, I began to notice Wunderkammer-like displays in contemporary web presentation. Perhaps the internet loves curiosity cabinets because it is, itself, a curiosity cabinet—in a manner of speaking, of course. Let’s take Pinterest as an example:

In the ecosystem of Pinterest we find the same organic arrangement of contrasting items, grouped poetically (rather than rationally) around a nebulous theme. The eclectic and exotic are prized; color and visual interest win the day. And the context for each item? Virtually nonexistent. The objects that made up a curiosity cabinet followed circuitous pathways (from Sri Lankan beaches and Amazonian jungles, say, to Parisian salons), in the course of which they lost their original contexts, names, meanings. Objects that had once embodied human culture, like sculptures and coins, became mere ephemerata. Natural treasures—corals, gems, ambergris, bezoars—likewise functioned as mere “curiosities.” Did that horn come from a unicorn or a narwhal? was a question few early moderns ventured to ask, because the items in curiosity cabinets did not invite speculation into origins. They had no labels, after all. No narratives. No “memories” as objects or images. So, too, with Pinterest and its ilk.

So is this all an elaborate critique of the likes of Pinterest and Tumblr for decontextualizing images—for encouraging digital Wunderkammer that prize variety at the expense of depth of knowledge? Sort of. But I also believe that the return of the curiosity cabinet aesthetic can be a good thing.

Some designers deride so-called “skeumorphic” design—decorative digital representations of old-fashioned physical objects, like brushed leather or woodgrain. Apple’s Newsstand is a prime example, and is Wunderkammer-like in its presentation, with individual icons glowing like jewels upon wooden shelving. Yet rather than relying on visual inspirations from the tacky material culture of the 1990s and 2000s (like the leather grain in Steve Job’ personal jet, perhaps we could take a cue from the microcosmic era of the curiosity cabinet.

What exactly do I mean by that? I’m not of course proposing that Apple’s designers start inserting dried seahorses into their compositions. Or even arguing that cluttered arrangements like those of Remps or Francken are particularly effective ways of presenting objects or information. However, I do think there’s something to be gained from paying attention to aesthetic forebears that lie outside the austere traditions of minimalism and modernism. Perhaps the pendulum is swinging back to a Baroque celebration of diversity of forms, asymmetry, eclecticism and a more poetic sensibility that injects a degree of intuition and randomness into the realms of machine intelligence and digital communication.

If so, I’d be all for it. I love curiosity cabinets. I love their clutter, their sense of mystery, and the ways they create surprising juxtaposition between objects and ideas that usually don’t belong together. The advantage this time around, though, is that now we can keep the labels on.

Recommended Links

- The Appendix on Pinterest

- Res Obscura on Curiosity Cabinets in the Seventeenth Century

- Bibliodyssey on Levinus Vincent’s wunderkammer

- Wolfram Koeppe on Wunder- and Kunst-Kammer

- Jessica Ezell of the UT School of Information on “The Internet as Cabinet of Curiosities”

- Robert Gehl of George Mason University on “YouTube As Archive: who will curate this digital wunderkammer?”

- Michelle Henning, “The World Wide Web as Wunderkammer” in James Lyons and John Plunkett (eds) Multimedia Histories (Exeter University Press 2007)

__Kunst-_und_Raritätenkammer_(1636)-medium.jpg)