Jean François de la Motte, Trompe l’oeil, 1660s

Jean François de la Motte, Trompe l’oeil, 1660s

Tempora Mutantur: Between Experimental and Narrative History

“The tymes are chaunged as Ouid sayeth, and wee are chaunged in the times.” -John Lyly, 1578

On a brisk April morning two years ago, I followed winding medieval streets to the Edinburgh University Library, an imposing concrete slab that houses some of the rarest and oldest books in Scotland. I was there to consult a set of letters between two 17th century natural philosophers and physicians, Sir Hans Sloane and Sir Robert Sibbald. Their exchanges were eye-opening: I began reading them expecting to witness science in the making, but in reality the correspondence between the two men was dominated by frustration and failure.

The problem was simple. Mail delivery between Edinburgh and London in the 1680s was still primitive, and often their packages never even reached one another. In his very first missive, Sibbald wrote of a book whose delivery “had miscarried.” The philosopher reflected forlornly, “it is not the first tyme I have been so served. My regret is that I am frustrated of seeing these fine things I am told are in that book.” Similar refrains continued over the years: in 1712, Sibbald tried to send Sloane some “curious books,” but his courier “had the misfortune to lose them and all his papers in a storme during the Voyage to London… he traveled by land and it seems fell in a river.” (To make matters even worse, the letter informing Sloane of this unhappy accident was dated Christmas Day).

As I continued to browse, I noticed a few lines written in charcoal pencil in the margins of one letter. The handwriting—a looping Victorian cursive—was very different from the cramped Baroque lettering of Sibbald. The annotation read as follows:

On Sat. 19 Feb 1848 a special train brought the budget of ministers to Edinburgh in nine and a half hours, from London.

AH.

Tempora mutantur. [‘the times are changed’].

Below this note, the author (AH?) had calculated the duration of the same trip in the era of Sibbald and Sloane: 100 days.

Times, as the Victorian author of the annotation suggested, had changed. And times continue to change. Today, documents like Sibbald’s books or the ministers’ budget don’t need to be carried as physical copies at all; they can be transmitted almost instantly online. From 100 days in the 17th century to nine hours in the 19th and nine milliseconds in the 21st.

Jost Amman, "The Printer’s Workshop," from The Book of Trades, Germany, 1568. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

History is shaped by the tools available for making it: cuneiform tablets tallying sheep or barley are less flexible as texts—they carry more limited forms of information, in smaller quantities, and in harder to reproduce form—than 17th century letters or printed books. By the same token, digital communication can do things that early modern technologies of writing and print can’t (for instance, web packets are at considerably less risk of falling into rivers during winter storms). History changes, and is also changed by, the technologies used to record it.

At the same time, however, history isn’t about those tools—it’s about people. People like Sibbald with his forlorn speculation about the “fine” contents of his lost books, or the hapless courier (Sibbald’s good-for-nothing cousin, the physician explained) who fell into the river. Or AH (whoever he or she was) and their proud boast about the speed of Victorian trains.

Finding a way to incorporate both these two approaches—the narrative and the experimental—is part of The Appendix’s mission. New digital tools like data visualizations, OCR, ebook databases, Google Ngrams, and “culturomics” are currently changing how we think about past as well as present. But how do we embrace the possibilities opened up by these technologies while remembering that history is about recovering individual lives as well as manipulating huge masses of information? Can we think big about the past while resisting the temptation to replace the “Great Men” theory of history with its 21st century counterpart, “Big Data”? (This is a topic that Tim Hitchcock, creator the Old Bailey Proceedings Online, one of my favorite digital history projects, has already written perceptively about.)

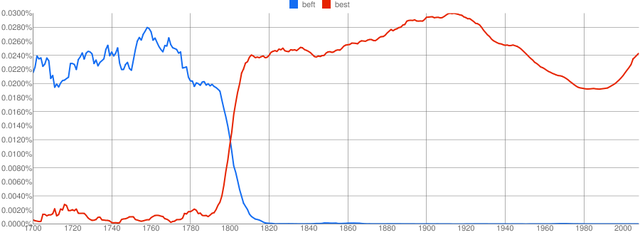

One of the most publicized new digital tools for understanding the past was the Google Ngram viewer, launched in December 2010 and updated in October 2012. Users can now analyze the contents of a total of 8 million books to find patterns in word usage.  Of course, critics were quick to point out that many aspects of Google’s data set were inadequate—text recognition has advanced rapidly in the past few years, but it still struggles with pre-20th century orthography, and the metadata for many Google Books is plainly wrong. Some of best uses of Ngram cleverly exploited the weaknesses of current text recognition technology, for instance by recognizing that computers (and many humans) mistake the pre-1800 “long s” as an “f.” The exact moment when the long s was abandoned can therefore be mapped by searching for “best” and “beft”:

Of course, critics were quick to point out that many aspects of Google’s data set were inadequate—text recognition has advanced rapidly in the past few years, but it still struggles with pre-20th century orthography, and the metadata for many Google Books is plainly wrong. Some of best uses of Ngram cleverly exploited the weaknesses of current text recognition technology, for instance by recognizing that computers (and many humans) mistake the pre-1800 “long s” as an “f.” The exact moment when the long s was abandoned can therefore be mapped by searching for “best” and “beft”:

Photo courtesy of Google Ngrams

Of course, many of the flaws critics pointed to in Google Ngrams—incomplete dataset, flawed metadata, and a tendency to overstate trends—are also present in traditional archival research. When I read the Sibbald-Sloane letters in Edinburgh on that spring day in 2010, had I unwittingly passed over a far more important book in the same archive? When the library closed and I had to finish my notetaking with some hasty skimming, did I miss a crucial piece of evidence in the book’s final pages? At a more basic level, I was tired that day, and my eyes hurt—perhaps I made critical errors in my transcription without realizing it. Digital history tools are still imperfect, but it’s worth remembering that human brains are too.

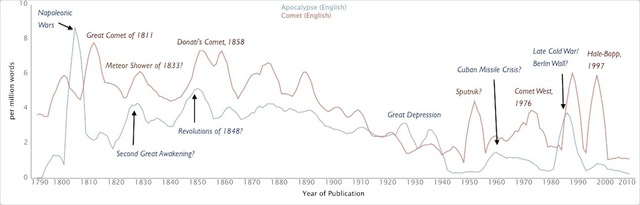

As an exercise in trying to join forces between these two flawed tools of historical inquiry, the brain and the computer, I spent a few hours today working with Bookworm, an Ngram-like lexical trend tool created by the talented Benjamin Schmidt and his colleagues at the Harvard Cultural Observatory. In keeping with the theme of the forthcoming issue (“The End?”) I searched for the word “Apocalypse” and one of the traditional astrological harbingers of doom, “comet,” in the period between the French Revolution and the present. I was curious to see:

- Whether the usage of the two words mapped onto one another, suggesting that comets corresponded with a rise of millenarian sentiment (or vice versa), and

- Whether I could link the blips in the data to actual historical comets and period of apocalyptic angst.

Here’s what I came up with:

At a few points—particularly the 1800-1815 period—I discerned what seemed to me like a clear correlate: the Napoleonic Wars, it would seem, led to increased apocalyptic fervor. This predated the 1811 Comet (“Napoleon’s Comet”) which was mentioned in Tolstoy’s War and Peace (and in contemporary works from that year) as a harbinger of the Second Coming and a symbol of Napoleon’s status as the Anti-Christ. The surge of mentions for “Apocalypse” in the 1845-50 period also gave me pause. Could this be related to the political unrest that precipitated the various revolutions of 1848? Here too, the spike in “apocalypse” preceded the spike in “comet” (which seemed roughly correspond to Donati’s comet in 1858.

Could it be that the types of comets which attract millenarian prophecies and doomsday predictions are those that immediately follow periods of political or military unrest? In other words, do human events predict how people conceptualize comets, rather than comets influencing human events?

Photo courtesy of Google Ngrams

As I thought about this, it occurred to me that I should check the Bookworm results (based on the public domain works of Open Library) against Ngram viewer, which searches all works available on Google Books. The corresponding graph from Google revealed that I might have been right about the spike of apocalyptic predictions during the Napoleonic era, but I was wrong about almost everything else. There’s no trace of the Cuban Missile Crisis or other Cold War events I thought I’d discerned in the “Apocalypse” data, and there are huge spikes that I can’t explain (I know of no major comet in 1800, but the spike for that year is significantly greater than the one for the infamous Great Comet of 1811).

In other words, I’m not yet prepared to use these tools in “real” scholarship because their results are too variable, and because they seem often to increase (rather than mediate) the subjective mistakes that human brains are prone to: humans love a pattern, and we tend to find them even where they don’t exist.

I want to end, by praising (and offering a measured critique of) another project of Benjamin Schmidt’s, one that he’s been slowly introducing on his blog Sapping Attention over the course of the past year or so.

Schmidt believes that “data visualizations are like narratives: they suggest interpretations, but don’t require them. A good data visualization, in fact, lets you see things the interpreter might have missed.” In the visualization above, Schmidt has drawn upon the Matthew Maury collection of American shipping logbooks, which spans roughly 1785 to 1860. Using tools from computer science like machine learning, Schmidt has plugged in the historical ship metadata and animated its change over time to show how whaling routes moved between the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean worlds.

As Schmidt notes, this sort of visualization is of interest to both scientists and historians. Historians and humanists, he argues, need to pay attention to “the swarm” or aggregate of populations and actions, because

the insistence… that history should be rooted in the archival experiences of individuals makes it much harder for us to explain some of the most important consequences of human actions in the world [like climate change and species loss]… While we want to tell only narratives in prose with human characters, this will be hard: the swarm is about aggregate behavior, not about individuals. Link

I share Schmidt’s belief that innovations in visualizing and analyzing history need to be taken to heart, not only to advance the discipline but, far more importantly, to bring history out of its bubble, to make it accessible to larger audiences, and to make it confront the very real problems we face as a society. On the other hand, I hope that The Appendix can point a way toward a middle ground between the narrative and the experimental, one that pushes us to examine the consequences of human actions, but which doesn’t let the individual get lost in the torrents of data that pervade our present, and, increasingly, our past as well.

In the months to come, we’ll be exploring in this blog and in the first issue of The Appendix the different ways that historians, humanists, artists, writers, web designers and scientists can come together to look at the past in a new light. We’ll be exploring the cutting edge of how technology can augment and expand the tools of history—but we’ll also be paying attention to actual lives, and arguing, passionately, that individual experiences still matter in history. We can’t let their voices get lost in the swarm of Big Data, lest we lose our own.