Doctored Beatles Images, Rolling Stone Puppies, and the Regression of History

In the middle of 1965—more than a year into the trans-cultural phenomenon of Beatlemania and the British Invasion—the East German pop music magazine Melodie und Rhythmus (Melody and Rhythm) published a rather poorly punned article titled “A Hairy Issue.” It begins with a fan letter from the Queens resident and Beatle-hysteric Cookie E.:

I was there when you arrived at Kennedy Airport in New York. I was almost killed and was only a meter and a half from you. Everything was crazy. I twisted my ankle and my dress was shredded. I have a scratch on my face and one eye is blue. Isn’t it wonderful? I worship you all.

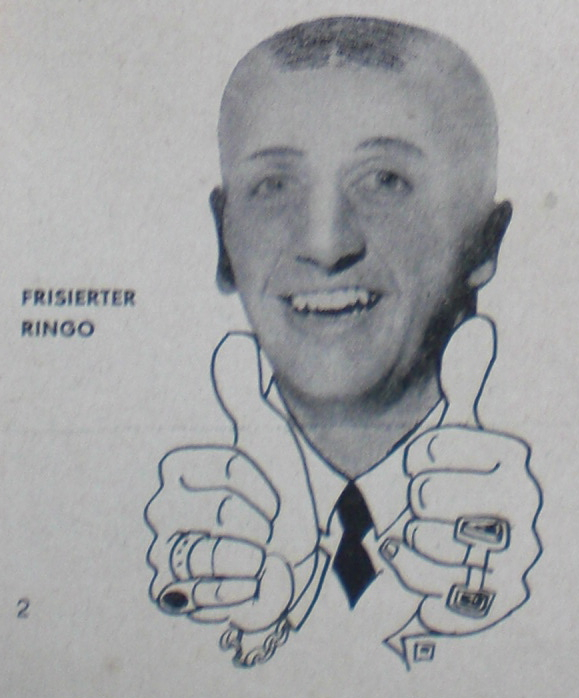

Below the letter, the photographed face of Ringo grins. Instead of his signature Beatle hair, however, someone has doctored the photo to give him a military-issue high and tight. Underneath, he gives a penciled-in two-thumbs-up with the gem-laden hands of some sort of caricatured Scrooge McDuck.

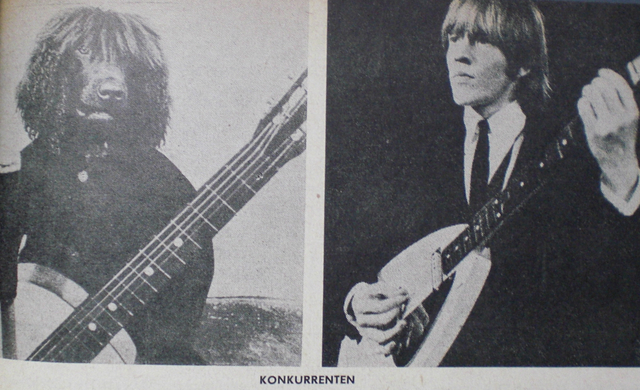

On the following page, there is a pictorial comparison and competition between two “rivals”: Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones (mop topped, suited, and wielding a Vox Mark VI) vs. a full-maned curly haired dog (standing up-right, dressed in an oversized dark sweater, and holding an unidentifiable acoustic guitar).

Why so much attention to hair in a piece ostensibly about music?

This focus on hair length and style was not an isolated phenomenon. East German newspapers, cultural bureaucrats, and policemen all had a minor obsession with youth coiffure. They consistently cited Beatle cuts as prime evidence of the danger the music posed and the degeneracy it actualized. The article, in many ways, sums up rather neatly the main fears and objections that official East Germany had to British Invasion, or, as Germans called it, Beat music. The music reduced socialist youth to little more than animals and, when properly trimmed and unmasked, the Fab Four were nothing more than agents in a nefarious plot by the Western military-industrial complex to invade the socialist countries and destroy it from within (hence Ringo’s buzz cut and banker attire).

But the article exposes other, more interesting things about the postwar reception of Beat music and the assumptions which surrounded it. Beyond showing that William Wegman was not nearly as original as we all had previously supposed, or that the East Germans had taken up the tried and true practice of Soviet photo-doctoring, the article’s hair-centered discussion and depiction of Brit Invasion points to a rather intriguing aspect of the socialist postwar interpretation of the sensory impact and composition of pop music.

The article clearly means to challenge the aesthetic status of the British boy bands and blues groups, but, interestingly, it avoids speaking about anything off the two groups’ most recent records. It says nothing of A Hard Day’s Night or 12 x 5 and, for that matter, it avoids discussing any recording or aspect of the group’s musical performance altogether.

For East German authorities and parents, Beatlemania and its children were not comprised of guitar-driven distortion, back beats, and limited vocal ranges alone. Beat wasn’t just sound, but was also something that showed up in the visual and tactile aspects of the body and on the person. It wasn’t something that just sounded unpleasant or simplistic but something that manifested itself in the nervous system, in behavior, and in one’s appearance. Beat was also long hair, unkempt and frivolous clothing, frenetic and unorthodox dancing, hysterical fits, violence, and/or loose attitudes towards sex. One 1965 East German report, for example, depicted a West German concert as a den of wild, hypnotized children who, because of their state, urinated all over themselves.

The fact that Western Beat appeared as more than sound is what proved most vexing and troubling. It wasn’t necessarily the sound of it that was objectionable—between 1964 and 1965, the state recorded and distributed some records and allowed local performances by East German bands like the Sputniks and the Butlers. The problem was that it seemed to be a whole mode of being and an array of sensory phenomena. In fact, it was its appearance as more than just sound that was one of the main problems. The East German musical ideal was based in the 19th century doctrine of Absolute Music: music should be pure, contemplative listening; it should offer access to a higher reality and, for some, the romantic Infinite through the ears. Music should ultimately be about the acoustic. Beat was clearly more than just aurality.

The Soviet Bloc was not alone in its condemnation of the Beatles and the Stones; English and American parents also fretted over the implications of screaming young girls and what they saw as androgynous musicians (in the case of the Beatles) or over-sexed and lurid boys (in the case of the Stones). What is fascinating about the Eastern response to Western pop music was that they invested the music with such power and social gravity. East German officials interpreted it as a challenge to both the goals of socialism and the progressive movement of History (which were, in their mind, essentially the same thing). Socialism offered the utopian promise of a society of creative, freely developed, and independent individuals—Marx’s vision of a person who could “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as [one had] a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.” That promise seemed to be thwarted through the conjunction of the rhythm and lyrics of Beat music and the style and attitudes of its audience. In the first two decades after the collapse of the Third Reich, the hope of a breakthrough into socialism had been pinned on the new generation of postwar youth, a generation who would grow up under socialism and be relatively free from the burdens of the recent capitalist and fascist past.

In late 1965, however, it seemed like the steam engine of Brian Jones was pushing History off the rails and into the ditch.