A detail from Trouble Comes to the Alchemist, Dutch School, 17th-century. Oil on canvas mounted on board, via the Chemical Heritage Foundation.

A detail from Trouble Comes to the Alchemist, Dutch School, 17th-century. Oil on canvas mounted on board, via the Chemical Heritage Foundation.

“Ravens-scull & a Handfull of Fennel”: Early Modern Drugs

I do remember an apothecary…

And in his needy shop a tortoise hung,

An alligator stuff’d, and other skins

Of ill-shaped fishes; and about his shelves

A beggarly account of empty boxes,

Green earthen pots, bladders and musty seeds,

Remnants of packthread and old cakes of roses.

-Romeo and Juliet, act five, scene one.

I spent much of the past year in Lisbon, Portugal, researching the development of the global trade in medicinal drugs during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. While there, I was struck by how extraordinarily different Portuguese pharmacies appeared from their United States counterparts. To be sure, many bore definite similarities to the type of American pharmacies I grew up regarding as normal: modern-looking edifices bathed in fluorescent light and painted a sterile white designed to set off the colorful packaging of the drugs for sale.

Others, however, (like the Farmácia Andrade, which I walked by nearly every day) looked more like this:

The Apoteket Storken (Stork Pharmacy) in Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Observant readers will note that this is a Stockholm apoteket rather than a Lisbon farmácia. This is also an especially grand and elegant permutation of the early modern pharmacy style. But the basics of this pharmacy mirror those found in the old parts of Lisbon: ceramic jars with hand-painted labels arranged on custom wood shelving, with an apothecary cabinet featuring dozens of tiny drawers beneath.

What is striking about these displays is how pre-modern they are. Indeed, the same basic design (ceramic jars of herbs, minerals and animal products lined on wooden shelves along with the occasional specimen of exotica) can be seen in engravings and paintings from the eighteenth century:

Pietro Longhi, The Apothecary, Italian, 1752. Note the prominently displayed aloe, an exotic and valuable plant at the time. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

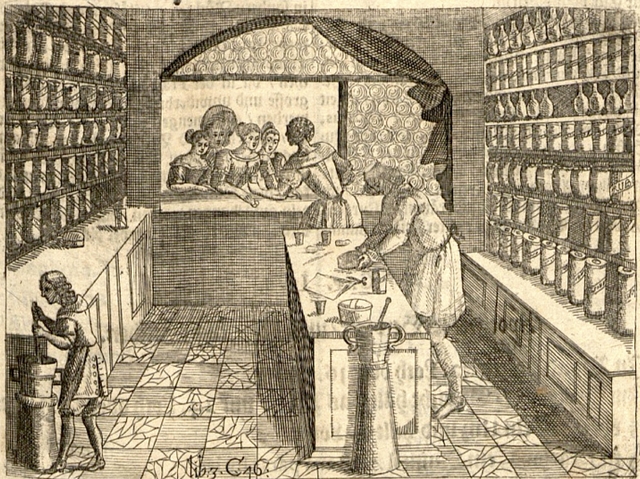

Or the seventeenth:

Wolfgang Helmhard Hohberg, Georgica curiosa aucta (Nuremberg: 1697). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yet what did these jars actually contain? Are there links beyond the purely aesthetic between early modern drugs and their modern counterparts?

Trying to actually learn the craft of early modern pharmacy is a difficult process: the apothecary was a member of a guild who held closely-guarded secrets, and apothecary manuals were frequently written in Latin and employed a host of specialist symbols and words like “drachms” and “scruples.” To make matters even more difficult, early modern drug lore predated the widespread adoption of Linnaean classification, so a plant called “Dragon’s blood” in Italian might be totally different from a plant with the same name in English.

What emerges when one overcomes these various obstacles and actually gets to the bottom of what was being prescribed, however, is a fascinating picture. It turns out early modern Europeans were prescribing some very familiar items—things found in herb teas sold in grocery stores today, like chamomile, fennel, licorice, and cardamom—alongside some utterly bizarre ones, like powdered crab’s eyes, Egyptian mummies, and human skull, or “cranium humanum.”

-medium.jpg)

Late 17th or early 18th century medicine jars that once contained human fat—one of several gruesome “cannibal medicine” remedies now forgotten by all except collectors of antique jars and historians of early modern medicine.

Below are a selection of medical recipes which I’ve transcribed from the rare book collections of the University of Pennsylvania and the National Archives of Portugal. Here’s hoping they come in handy next time you suffer from consumption, rickets, or “fitts.”

The following are from the Van Pelt Library (University of Pennsylvania) MS Codex 388, circa 1699-1703:

To make Snaill water, for a consumption, or anny weakness in old or young persons, and for the ricketts

Take a quart of snails, wash them twice in stronge-stale-beere and dry them well in a cloth, then bruse them shels and all. Put to them 3 quarts of red cows-milk 4 ounces, red rose leaves, Rosemary, sweet-marjoram, Ivery, of each a good handfull. Distill altogether and sweeten your water with surrop of violets, and sugar candy lickerish sorrop. Put in 6 penny-worth of naturall-ballsom. Drink a quarter of a pint of this every night and morning.

To make powder for convoltion-fitts

Dry three ravensculls and the head of a he[dge]-hog to powder and take as much every morning as will hang on a shilling.

I especially like the pièce de résistance in this collection, the “surrop” for “convoltion-fitts” (likely meaning epilepsy) which contains everything from aniseed, ale, and peony roots to “dead mans scull” and sulfuric acid, i.e. “salt vitrell” or oil of vitriol. I have slightly modernized the punctuation but left spelling in its original form:

To cure convoltion-fitts, a surrop

Take a handfull of single-pyeany roots, 2 handfull white lilly-rootes, Pallopodiam rootes, mugwort roots, and leaves of horehound, of each a handfull, [plus] two ounces annyseeds, a handfull fennel rootes, three ounces lickerish, one handfull pelitary of the wall. Boyl all together in 3 quarts of water tell it comes to 3 pints, then take a pound of suger, boyl it a quarter of an hour, put it to coole, and bottell it, take a quarter of a pint the furst thing in the morning.

Then an hour after breckfast, take 25 drops of sallamoneck (i.e. salamoniac ), in a glass of beere…

At the full of the moon, if the fits be bad… take a cardias vomet, with 2 papers of salt [of] vittrell [vitriol] to make it work, and then let blood. If you take Stron[g]-Ale a fortnight after you have done takeing thes things, and continue the takeing 3 weeks, takeing 2 purges after, it will be of great use to make a perfect cure, but this course must be repeated every spring and fall. If the person finds any return of the fitts, take sumtimes a spoonfull of assafettita watter. You must take powder of raven-scull or dead mans scull in the surrop every morning or night as will fit on a six-pence.

The mixed-up nature of early modern medicine—the mixing of medieval or Greco-Roman astrological theories of man as microcosm with exotic drugs derived from colonial expansion into the tropical world—is highly evident here. The author of this book was prescribing items ranging from things one could find in one’s backyard in England circa 1700, like ale, fennel or (God forbid) a hedge-hog’s head, to exotica that would have cost a small fortune to purchase in bulk, like asfoetida imported from India or ivory from Africa.

The same mixture is found in Portuguese texts. Here, an anonymous Portuguese official stationed in 18th century Mozambique offered a panorama of the various drugs to be found in the Africa:

Among the roots of Africa that have medicinal virtue, there are the species of calumba; the “little potato of Mixonga” that is used for fevers and indigestions; there are also the abutua to treat swellings; and the fever root also called “Fastio root.” However it is certain that the Manica root is, out of all of them, the most mysterious for malign fevers, and as an antidote, and has other further virtues that are known to the curious.

There are also an immense number of herbs of diverse virtues… [such as] the “milk of mamano,” which is vulgarly called in Africa Mono, and in other parts “figs of hell.” AN/TT, Ministerio do Reino.

Or the Franco-Portuguese apothecary João Vigier, whose 1716 list of “modern drugs” (drogas modernas) from Brazil and the Indies included a rare pre-19th century mention of coca leaves (“the bark of the anda fruit is good against curses, and kills fish, as does the coca to the west [of Brazil]”) as well as the following curious entry for a drug called Balm of Gilead:

This balm comforts the vital parts and excites semen… [however] the Grand Turk has taken all of these plants for his own use… They are guarded carefully by his Janisarries in Cairo.