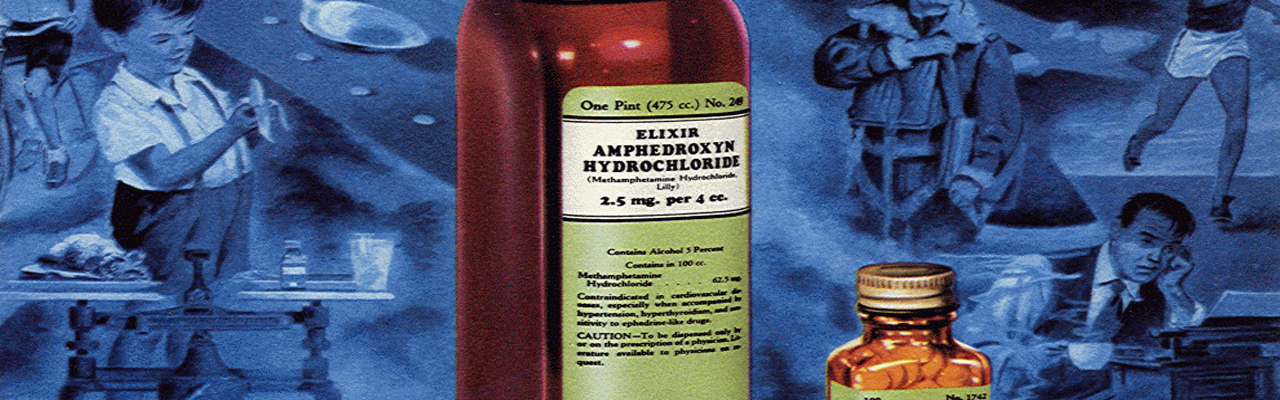

An advertisement for methamphetamine from 1951 which recommends the drug for treatment of obesity with “a minimum of undesirable excitement and other side-effects.”

An advertisement for methamphetamine from 1951 which recommends the drug for treatment of obesity with “a minimum of undesirable excitement and other side-effects.”

An Appendix Miscellany: Foods and Drugs

In the 17th century, when traditional newspapers and journals were roughly as new as their electronic brethren are today, miscellanies proliferated. Profit-seeking astrologers (like Jonathan Swift’s parodic persona Isaac Bickerstaff) published guides to the new year filled with predictions of prodigies, disasters and miracles, while weekly periodicals like Mist’s Weekly Journal rounded up information from all corners of the world and repackaged it as haphazard lists: reports of strange happenings in Istanbul, Lisbon, Philadelphia, Tangiers and Buenos Aires might all appear in the same block of text in an early newspaper.

Being an early modern historian, I love this way of presenting information; thus, I also love Lapham’s Quarterly, the new-ish literary digest that is concerned with “bringing up to the microphone of the present the advice and counsel of the past.” I especially liked their recent miscellany of lore related to drugs and intoxication, “Bombs, Burning Sheets and Cocaine.” The editors at Lapham’s covered a lot of ground, but I thought it would be fun to add my own list of drug-related miscellany.

Today seemed an especially auspicious day for such a list, because it ties in with our newest Appendix article, food historian Rachel Herrmann’s “Death by Chamomile?” Herrmann weaves a fascinating tale that involves a (potentially) poisoned cup of chamomile tea drunk by an African prince en route to Sierra Leone, which led to a series of misunderstandings that culminated in a trial by poison via the noxious Calabar bean. With that context in mind, here are some other appearances of drugs and foods in the historical record:

- Although the various legends of a bushel of tomatoes being eaten in a Revolutionary War-era town square (reputedly by one Colonel Robert Gibbon Johnson in Salem, NJ) in order to publicly demonstrate their harmless nature are likely apocryphal, it is true that many premodern eaters feared tomatoes. This was mainly due to their similarity to deadly nightshade, with which the common tomato plant is in fact closely related.

- In his New General Atlas (London, 1720), the geographer John Senex left an intriguing report of opium and cannabis use in early modern Iran. Persian men were known to be “excessive in the Use of Opium,” Senex wrote disapprovingly. “Some take an Ounce at a time, which makes them giddy. They think it inspires them with Courage. The Women seldom use it, but to rid themselves from the Cruelty of their Husbands, and then take a great Quantity, drink Cold Water or Vinegar after it, which makes them die without much Pain.” After this sad aside, Senex noted as well that Persians “of Quality delight so much in Tobacco, that they smoke it in the Mosques,” while others “smoke Hemp, which puts them by their Senses for two or three Hours, and makes them either pleasant or stark mad.”

- Harry “the Hipster” Gibson was an up-and-coming New York-based singer known for his rakish persona in 1947, when his risque song “Who Put the Benzadrine in Mrs. Murphy’s Ovaltine?” earned him a spot on the music industry’s blacklist. Benzadrine was a trade name for amphetamine, popular both as “pep pills” among WW2 pilots and among the emerging Post-War counterculture, including jazz, blues and rockabilly musicians and writers of the Beat Generation. Gibson is today mainly remembered for the song that torpedoed his career; it is one of the earliest pop songs to feature explicit reference to drug use in its title.

Harry “The Hipster” Gibson with his band in New York, July 1948, as photographed by William Gottlieb. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

- In December of 1689, English scientist Robert Hooke (co-discoverer of cells, among other things) reported his recent experiments with a “a certain Plant which grows very common in India” that he called bangue. When dosed with the drug, Hooke reported, “The Patient understands not, nor remembereth any Thing … but becomes, as it were, a mere Natural, being unable to speak a Word of Sense; yet is he very merry, and laughs, and sings, and speaks Words without any Coherence, not knowing what he saith or doth.” Hooke noted, however, that this anonymous patient was “not giddy, or drunk, but walks and dances, and sheweth many odd Tricks,” eventually falling into a deep sleep and awaking famished. Hooke’s opinion of the drug was that “there is no Cause of Fear, tho’ possibly there may be of Laughter.” Bangue, as you may have guessed, is cannabis.

- In 2009, the New York Times reported that the infamous Columbian drug dealer Pablo Escobar had left behind a menagerie of exotic animals following his death. The reporter travelled with a team of commandos stalking Pepe, a hippopotamus once owned by Escobar that had made a new home in the jungle and was posing a threat to locals. “He needed a tranquil place to unwind with his family,” an associate of Escobar’s offered as explanation for his imported kangaroos, rhinos and hippos. With an estimated peak net worth of up to 30 billion USD from the Medellin cartel’s cocaine sales, he could afford it.

- As historian Carol Benedict explains in her book Golden-Silk Smoke: a History of Tobacco in China, some of the earliest blends of tobacco to catch on in China in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were mixed with southeast Asian spices like cloves, nutmeg and even civet musk. Although modern clove cigarettes were invented in 1880s Java, similar blends of tobacco with cloves were prevalent in the trading worlds of Southeast Asia since early modern times. Mixing tobacco with opium also became a popular practice among European traders in East Asia, setting in motion the chain of events that would lead to the Opium Wars.

- Medical consumers used to eat Egyptian mummies in large quantities in order to cure diseases like plague and epilepsy.

- Methamphetamine is still approved by the FDA as a weight-loss drug, although it is almost never prescribed for this purpose these days. In the 1950s, however, it appears to have been quite normal for a doctor to prescribe meth for, say, a plump child to lose weight, or for a housewife who wanted to put a little more pep in her step. Pharmaceutical ads touting meth bragged of its safety profile.

This 1951 Eli Lilly advertisement recommends methamphetamine as a “prudent choice” for “depression, narcolepsy, alcoholism, or obesity.” Courtesy of the Bonkers Institute

- Writing in 1630s Canada, the French Jesuit Paul Le Jeune recorded a conversation between two Míkmaq Indians debating the merits of brandy and other alcoholic spirits. According to the Jesuit, one native man said that “It is not these drinks that take away our lives, but your [European] writings; for since you have described our country, our rivers, our lands, and our woods, we are all dying, which did not happen until you came here.” Le Jeune then “told them that we described the whole world,— that we described our own country, that of the Hurons, of the Hiroquois, in short, the whole earth; and yet they did not die elsewhere as they did in their country. It must be, then, that their deaths arose from other causes.”

- Bezoar stones, concretions that form in the stomachs of certain goats and llamas, were once worth far more than their weight in gold because they were believed to be a universal antidote to poison. Although the practice of eating ungulate hairballs has fallen out of fashion, can still find marvelously crafted bezoar containers in museums, like this one at the Met.

- According to drug historian David Courtwright, “By 1885 taxes on alcohol, tobacco, and tea accounted for close to half of the British government’s gross income. Drug taxation was the fiscal cornerstone of the modern state, and the chief financial prop of European colonial empires.”

- A medicine called Koehler’s One-Night-Cough Cure popular in the 1890s had the following active ingredients: cannabis, chloroform, morphine and alcohol, “skillfully combined with other common ingredients.”

- The quinine in tonic water (which was originally derived from the Amazonian plant Cinchona officinalis) possesses the unusual property of flourescing under ultraviolet light. Indeed, pure cinchona infused in water apparently even gives off a faint glow in direct sunlight, owing to the UV rays present in full spectrum light.