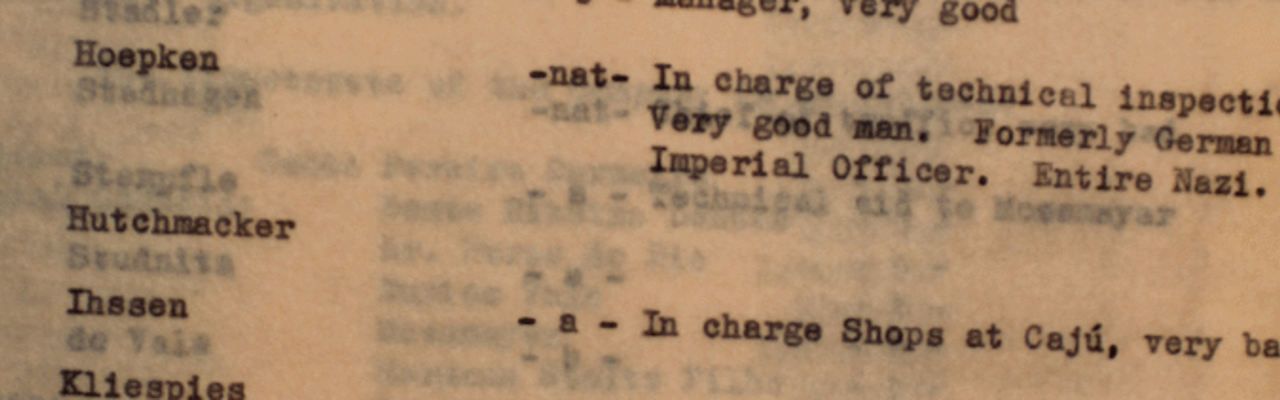

List of German employees in Brazilian airlines, listing them as “good,” “bad” or “Nazi”—declassified from the U.S. Army intelligence files

List of German employees in Brazilian airlines, listing them as “good,” “bad” or “Nazi”—declassified from the U.S. Army intelligence files

Nazis in the Amazon Revisited: the Power of Rumor and Gossip

Back in November I posted in this blog a series of declassified U.S. intelligence documents. They dated from 1941 and 1942, and spelled out American fears of Nazi infiltration in the Amazon—particularly secret airfields that might be used to launch an attack on the Panama Canal from the Amazon. As Dr Brett Holman pointed out in his Airminded Blog, these documents were not related to each other, and seemed to indicate a proliferation of rumors regarding German infiltration. That gave me pause, and I started to consider the role of rumors and gossip in history.

Let us consider some of the questions raised by Dr Holman in his blog:

But there’s also the question of the source of these rumours: they may not be such a clear analogue to the earlier Australian episode after all. Just who was passing these stories of secret German airfields around? Was it ordinary Brazilians? Brazilian military personnel? Expatriate American or German residents? It makes a difference, because such stories would mean different things, and would be used for a different purpose, by different audiences. Did Brazilians themselves fear German infiltration? I doubt they were as worried about a German air raid on the Panama Canal as the Americans were. I need to know more!

First a little background as to the German community in Brazil. Germans had been immigrating to Brazil since the mid 19th century, and had established large German speaking communities, especially in the southern portion of the country. By the 1930s, as Hitler came to power and German airline subsidiaries became major players in Brazilian aviation, there was already a sizable population of Germans and their descendants living in Brazil. There was also a Brazilian fascist political party, the Integralistas, which was composed of Brazilians as well as their German immigrant counterparts. The Integralistas wore green shirts (much like the Nazi brown shirts) and black armbands with the Sigma (like their German counterparts with Swastikas).

So how influential were the Brazilian fascists, the Integralistas? They certainly had friends in high places, such as the presidential cabinet—although they were persecuted by the government after their failed coup d’état attempt in 1938. (Note that the Brazilian Communist Party had also attempted to oust the dictator Getúlio Vargas earlier in 1935). Needless to say, U.S. Army intelligence truly had something to worry about in this period of Italo-German style fascism in Brazil.

Now, back to our documents. It is hard to tell the particular source for the three documents I presented, as even J. Edgar Hoover says that his “reliable confidential source” merely mentioned “rumors” of a German airbase. While these particular plots cannot be substantiated, Axis spies or fascist collaborators certainly existed in Brazil before and during the war. The Brazilian secret police, the DOPS (Department of Social and Political Order) worked together with the American FBI and arrested several German spies with secret shortwave radio broadcasting equipment.

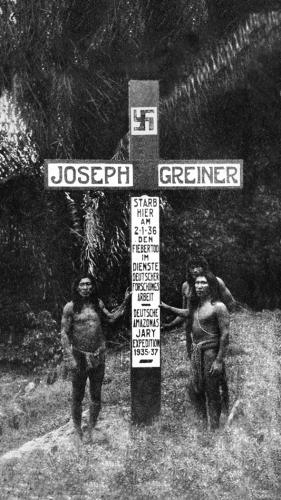

As to Nazi infiltration in the Amazon specifically, we cannot tell from the documents how many, if any, German agents were present in the region during the war. One thing we can tell, however, is that they were very active in the area throughout the 1930s. One German scientist, Otto Schulz-Kampfhenkel, spent two years traveling throughout the Amazon valley with a large expedition and a hydroplane — collecting biological specimens but also rendering detailed maps of the region. The biological, cartographic and even ethnographic information they collected was valuable also to the Brazilian government, which was still trying to extend its power in the region. When Otto returned home, he suggested to Heinrich Himmler that the Amazon could offer “spacious immigration and settlement possibilities for the Nordic peoples”—revealing that at least some of their motivations were ultimately of a colonial nature. The Japanese, for one, in fact did have a colony in the Amazon which among other things produced black pepper. They even considered it to be their territory, as I have read the account of one Brazilian pilot who, after making an emergency landing there, was held captive by the Japanese “consul,” despite obviously being in Brazil.

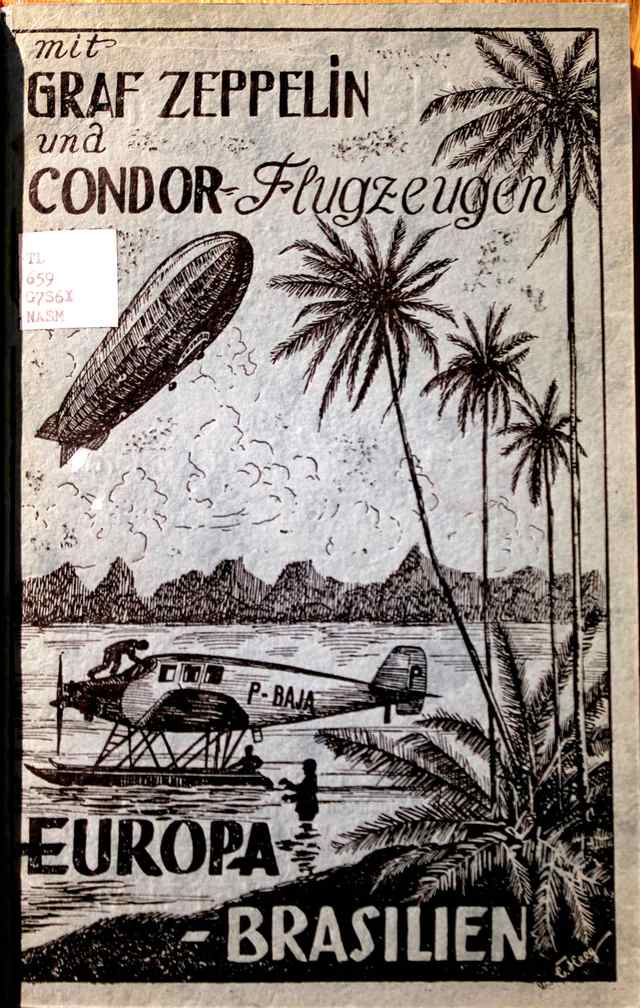

Another expedition involved an over flight of the Amazon river by a Zeppelin—and while the Brazilian military forbade them to film their trip while passing over an Army base, they extensively filmed and photographed the rest of their route. That is, before World War Two rolled around, the Germans had collected extensive information on the Amazonian region, maybe even more than the Americans, who started building their bases there in 1942 as Brazil finally joined the war on the Allied side.

But who came up with the later rumors? It is hard to know, but as Brett Holman pointed out, it makes all the difference. Let’s assume for a second these rumors are not true. Why would they come about? What would be one’s motivation to generate such a scare? Brazilian military officers, for one, could gain further military support and equipment from the U.S. if there were a risk of German infiltration. Brazilian fascists could, by exaggerating German power in the Amazon, strengthen their cause. But let’s not forget that the reasons behind rumors can potentially be much simpler and very petty—one could, in a time of war in a repressive state, get rid of enemies by falsely accusing them and having them imprisoned.

Militaries or intelligence agencies have often used rumors to achieve their own ends. Operation Bodyguard, employed by the allies to confuse the Germans as to the location of the D-Day landing, used a complex network of rumors to distract German intelligence from the actual landing site. Operation PBSucess, the CIA’s predecessor to the Bay of Pigs, used rumors of a phantom army moving through Central America to successfully overthrow the democratically elected government of Guatemala in 1954. The rumors were propelled by radio broadcasts made from an antenna hidden under the roof of the U.S. embassy in Guatemala City.

But the CIA and major armies at war are not the only ones to employ rumors. People far from having such power, such as peasants, have long used rumor for their own ends, to advance their own messages. Consider the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 in India. The British officers of the East India Company issued rifle cartridges greased with cow and pork fat—a great offense to the sepoys, the Hindu and Muslim troops serving under the East India Company. But as rumors travelled about this particular incident, the actual information was transformed by those who had suffered the transgression. Soon, people were hearing that the British intended to forcibly convert them to Christianity and prohibit agriculture. That is, the rumors shifted in a way that brought more and more people into open rebellion against the East India Company. Rumors and gossip, travelling like wind through the population, can be powerful agents. So much so that the Roman Empire had a cadre of officials, the delatores, which collected and reported gossip.

We can see how the rumors have had an important role in history. Rumors of military airplanes, dirigibles and secret airfields were particularly scary and potent during the first half of the twentieth century. Dr Brett Holman’s work focuses heavily on this, something you can see throughout his Airminded Blog. I personally recommend his book, The Scareship Age, 1892-1946, which he generously offers as a free e-book download in his website.