Froger’s Capybara and the Metaphysics of Memes

In one of the first Appendix blog posts, I reflected on the ways that the internet decontextualized images and information, and argued that this bears a resemblance to the early modern European “curiosity cabinet” aesthetic, which jumbled together things like Sri Lankan gems, Inuit carvings, taxidermied animals and Andean bezoar stones. These collections inspired wonder in the viewer via their visual variety, largely ignoring the internal narratives of the objects they contained. Such items, I wrote,

followed circuitous pathways (from Sri Lankan beaches and Amazonian jungles, say, to Parisian salons), in the course of which they lost their original contexts, names, meanings. Objects that had once embodied human culture, like sculptures and coins, became mere ephemerata. Natural treasures—corals, gems, ambergris, bezoars—likewise functioned as mere “curiosities.” Did that horn come from a unicorn or a narwhal? was a question few early moderns ventured to ask, because the items in curiosity cabinets did not invite speculation into origins. They had no labels, after all. No narratives. No “memories” as objects or images.

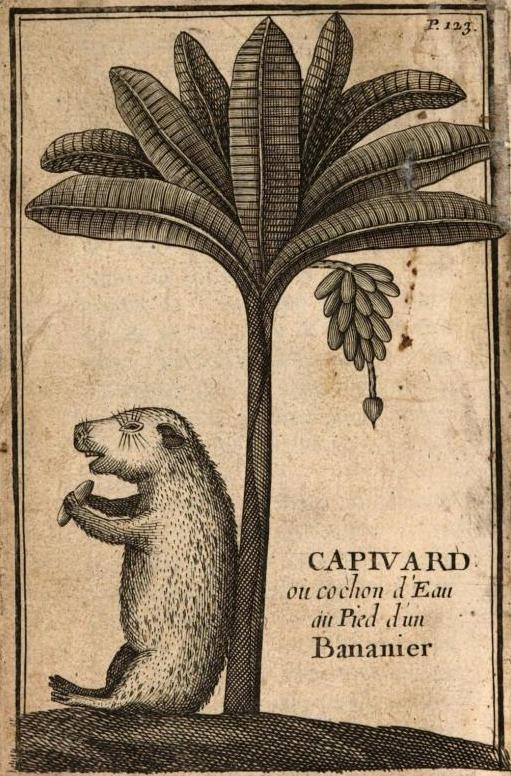

It occurred to me that the tale of Froger’s capybara—an engraving from a 1698 book of voyages to Africa and Brazil written when the author was just twenty-two years old—is a good case study of this process. First, the image itself, featured in the section of Froger’s narrative regarding his travels in the area around Rio de Janeiro:

Pg. 123, “Capivard, ou cochon d’Eau au Pied d’un Bananier,” in François Froger, Relation d’un voyage fait en 1695, 1696, et 1697 aux côtes d’Afrique (Paris, 1698).

As you can see, there is something inherently striking about this image of what Froger calls a “Capivard, or hog of the water, at the foot of a banana tree.” It hits all three of the aesthetic categories that Stanford professor Sianne Ngai has argued are characteristic of our age: the cute, the zany, and the interesting. And beyond that, it has a fundamental strangeness to it, especially in the eye of the capybara which gazes back at us, its lashes like rays from a sun.

I distinctly remember when I first saw the image: it was the 9th of April, 2012, and I was perusing Froger’s book in the reading room of the National Library of Portugal, in Lisbon. It was a lazy late afternoon, and sunlight passing through the tall, partially shuttered windows was casting stripes of light and shadow on the several dozen readers and librarians. Finding the engraving both energized me and distracted me. I found it instantly fascinating—too much so, in fact, since I proceeded to extract the image from the Google book scan of Froger’s Voyages, post it to Facebook and lost the rest of the work day to internet browsing. Then I forgot about it.

An actual capybara, photographed by Corey Van Loon at a Dutch zoo last year sporting a complement of monkeys.

A few weeks ago, I noticed it again: now it had appeared on the Pinterest page of the Public Domain Review and received a healthy following on Tumblr. The image has even been printed onto a “protective phone sock” sold on Amazon.com. Froger’s capybara, in a very minor way, had become an internet meme.

What did this entail? When I first posted the image, I added a bit of context from Froger’s actual writings. (Here I present a more complete translation):

We brought three oxen, a few chickens, a tiger-cat, and another animal quite extraordinary, that the Portuguese call ‘Capivard,’ which has the body of a pig, the head of a rabbit, and thick hair the color of ash: it has no tail at all, and sits on its rear quarters like a monkey. It is almost always in the water, and does not venture onto land except at night when it ravages all of the gardens and trees that have fruit.

I suspect that my posting was the root of the capivard “going viral” in its minor way, because as it passed through Tumblr it initially retained my citation of Froger and translation of the passage in question. By now, however, it has passed from this stage of quasi-contextualization to simply being a deracinated image floating around the internet.

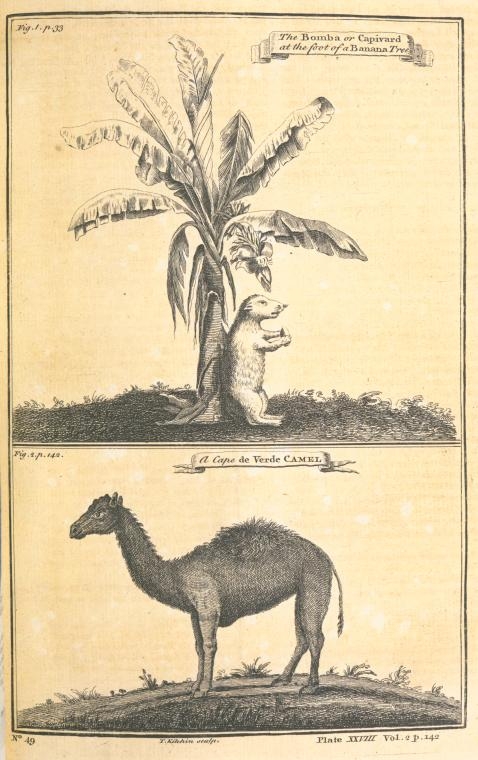

Which, in the end, makes a strange kind of sense. After all, early modern Europeans had no modern sense of ownership over an image or text, and they reprinted and reused the “memes” of their day without qualms. Indeed, Froger’s capybara has been circulating throughout the world far before I laid eyes on it in Lisbon last April—or, for that matter, before a Google engineer first uploaded the image onto the web in 2010. In this engraving from 1745, for instance, we find our “water hog” flipped around, re-imagined, and rendered into English:

Plate 142, John Green, A new general collection of voyages and travels (London, 1745-7). Image via the New York Public Library

It would seem that eighteenth century readers found the image as compelling as their twenty-first century counterparts. Here something far beyond the decontextualization of the internet has occurred: while the technology of the web allows perfect reproductions of images, printing is different: each time a copper plate or woodblock hits ink and the page, the image it contains is changed in an infinitesimal way. More importantly, when a competing publisher wanted to use such an image, they had to hire an artist to emulate it rather than duplicate it outright. Hence the odd features of the English capybara, which looks more ratlike and less true to life.

Finally, however, its worth reflecting on how the image even reached engravers and printers in Europe. Froger doesn’t say if the engraving was based on a drawing by himself or one of his companions, or if he narrated a description of the strange creature to an engraver in France. Yet we know from other, similar travel accounts that there could be significant differences between “on site” drawings by travelers in the New World and the engravings produced from them.

At left: John White, “A cheife Herowans wyfe of Pomeoc and her daughter,” 1585. Center: Engraving from Thomas Hariot’s A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia (1590). Right: Mughal Indian watercolor, author unknown, 1630s.

In these three striking images, we find the Virginia colonist John White’s painting of an Indian chief’s wife re-imagined, first, by the engraver named Theodor de Bry and, more surprisingly, by a Mughal watercolor painter. As the image passes from the reality observed by White to the sketch he produced, the engraving copied from it, and the watercolor copied from that, we find the same process of decontextualization at work. The wampum beads worn by the Indian woman become a string of pearls; her tunic changes from brown to scarlet to blue and gold; her facial features morph to conform to Native American, European and South Asian ideals of beauty. But despite the changes, we are looking at the same person.

Or are we?

Presumably on some afternoon in Brazil in June of 1696, a capybara did in fact sit down under a banana tree to have a snack, and Sieur Froget happened to notice her. When we look into the eye of the capivard that appears to us via a re-post of a scan of an engraving of a drawing of a “real” natural scene, what exactly are we looking at? Such an exercise invites reflection on what will happen as the internet ages, and images continue to circulate for decades or even centuries, losing their metadata and contexts, but (and here the break with print culture is a clear one) retaining their basic form. When we look into the knowing eye of Froger’s capybara, it is interesting to reflect on how many layers of perception and reproduction that single event in time has passed through to reach us today—and to meditate on how many aeons into the future this record of a chance encounter in Brazil will endure, preserved in amber, as it were, by the seemingly immortal medium of the internet.