A rowdy detail from Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam, which was painted onto a bed sheet in 1758.

A rowdy detail from Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam, which was painted onto a bed sheet in 1758.

“A Toast to Your Health”: Getting Drunk in Colonial America

To say colonists living in early American society were enthusiastic about drinking would be a remarkable understatement. Modern estimates place the annual amount consumed by the colonists somewhere in the range of five to six gallons of pure alcohol (by comparison, per capita consumption in the United States in 2007 came in around 2.3 gallons).

During his travels along the eastern seaboard, Dr. Alexander Hamilton noted that one was expected to keep pace with their hosts while in the tavern, or risk insulting the surrounding company. Alcohol formed an integral part of colonial life: indeed, it is estimated that there were more taverns per capita than any other business in colonial America. According to visitors to the colonies, one of the favorite, alcohol-related pastimes that could seemingly go on without end was the raising of glasses in a toast.

Toasting, or ‘drinking healths,’ was a longstanding tradition in English culture. The act of honoring another and drinking to their health was a way for English drinkers to combine a display of respect with the consumption of alcohol—certainly a win-win situation for those who favored the practice. The act itself, while popular among the English, didn’t always gain favor from outside observers. Voltaire, in his Dictionnaire philosophique, criticized drinking to another’s health—an act that he described as unique to the English. Claiming that the English took up the custom in order to mimic the ancient Romans, Voltaire saw little point to the overall act. “It is very likely that hence the custom arose, among barbarous nations,” Voltaire wrote, “of drinking to the health of their guests; an absurd custom, since we may drink four bottles without doing them the least good.”

John Greenwood, Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam, c. 1758, oil on ‘bed ticking.’ Via Wikimedia Commons

Whether or not the act of drinking to another’s health actually benefitted that person was of little concern to the English, and they carried on in spite of such critiques. Like other cultural traits carried by the seventeenth and eighteenth century migrants, the custom of ‘drinking healths’ traversed the Atlantic and promptly became an established part of daily life for tavern patrons across British North America.

While criticism of an English custom by a French philosopher would surprise few, the act of toasting also met criticism in the colonies, as figures of authority came to view the practice as disruptive and encouraging drunkenness. A Boston judge, one Samuel Sewall, encountered frustrating resistance when he attempted to disperse a rowdy tavern crowd in 1714. In spite of his attempts, Sewall failed to convince the members of the party to return to their homes. He complained, “They refused to go away. [They] said [they] were there to drink the Queen’s health, and they had many other healths to drink.” Sewall, far from willing to participate in the on-going fun shared between the drinkers, ending up turning the assembled crowd against him through his attempts to end the festivities. Instead of following the judge’s orders, the tavern crowd began to mock Sewall by sarcastically drinking to his health. “[They] call’d for more drink; drank to me; I took notice of the affront… I threatened to send some of them to prison; that did not move them.” Sewall, angered by his failure to halt the drinkers’ rambunctious behavior and frustrated by the crowd’s blatant act of disrespect (by drinking to his health, no less), admitted defeat and left the tavern patrons to carry on as they pleased.

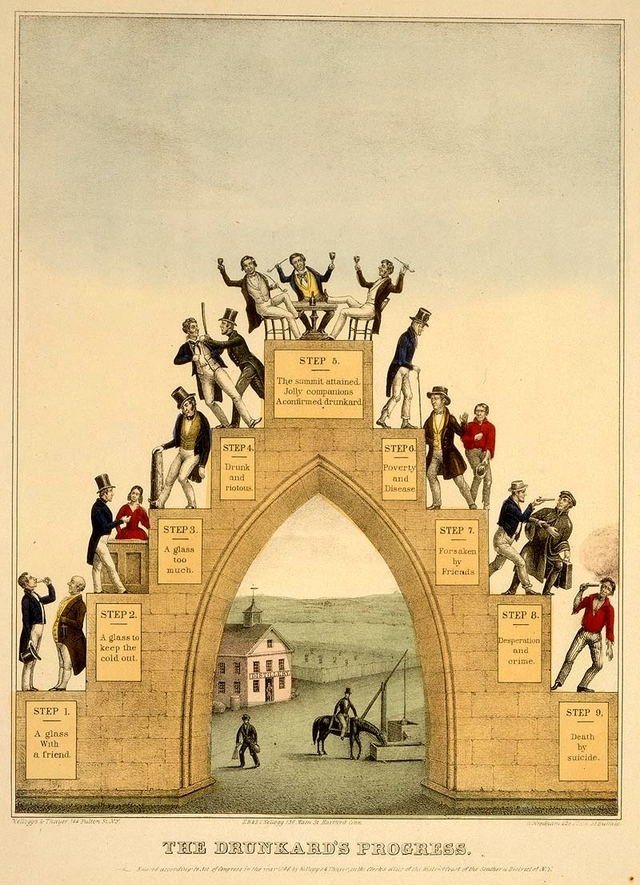

“The Drunkard’s Progress,” anonymous print, 1846. By the early nineteenth century, the culture of heavy drinking in North America had given rise to a home-grown temperance movement. Via Wikimedia Commons

The Judge held no authority over this assembled gathering, and he felt certain their behavior would dissolve to that of a mob, but such violence did not follow. The assembled drinkers (though at that point, possibly drunkards) in the tavern instead satisfied their thirst, drank to all the healths they felt to be necessary, and eventually wandered home—though, the following day, the tavern-goers were fined five shillings for their disrespect.

Not always understood, and at times criticized, ‘drinking healths’ continued to remain a favorite way of passing the time in the American colonies. With such an appetite for intoxicating liquors, the colonists lacked no excuse for imbibing their favorite beverages, but this old English custom certainly made the act more entertaining for assembled groups like the one described by Sewall. Voltaire viewed the act as a mark of inferiority for the English (and superiority of the French by default). Were the colonists to hear such a statement, this historian can’t help but imagine that they would simply respond by raising a glass.