The Appendix Wishes You a Happy Wolf Day

You may have heard that Valentine’s Day has its true origins in a pre-Christian festival, Lupercalia. But few know the details of how our contemporary holiday of commercialized romance began as a Bronze Age rite celebrating the primordial power of the wolf. With that in mind, we at the The Appendix would like to wish you a happy Lupercalia, and invite you to read on.

The story of Valentine’s Day begins with the legend of King Lycaon (“The Wolfish One”). According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Lycaon was a primitive lord of Arcadia during the earliest eras when humans walked the earth, a time “when the constellations that had been hidden for a long time in dark fog began to blaze out throughout the whole sky.” Yet Lycaon was a king of the Iron Age, when “honour vanished” and “pernicious desires” reigned:

They set sails to the wind, though as yet the seamen had poor knowledge of their use, and the ships’ keels that once were trees standing amongst high mountains, now leaped through uncharted waves. The land that was once common to all, as the light of the sun is, and the air, was marked out to its furthest boundaries by wary surveyors. Not only did they demand the crops and the food the rich soil owed them, but they entered the bowels of the earth, and excavating brought up the wealth it had concealed in Stygian shade, wealth that incites men to crime… I: 125-50

“Lycaon,” 1589. Engraving by Hendrik Goltzius (1558-1617) for Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book I, 209 ff. Via Wikimedia Commons

Lycaon was among the worst of a bad lot. His infamous crime was to attempt to trick Zeus into eating the limbs of a dismembered child in order to test his omniscience. But as Zeus himself described, the king of the gods was not fooled:

No sooner were these [limbs] placed on the table than I brought the roof down on the household gods, with my avenging flames, those gods worthy of such a master. [Lycaon] himself ran in terror, and reaching the silent fields howled aloud, frustrated of speech. Foaming at the mouth, and greedy as ever for killing, he turned against the sheep, still delighting in blood. His clothes became bristling hair, his arms became legs. He was a wolf, but kept some vestige of his former shape. There were the same grey hairs, the same violent face, the same glittering eyes, the same savage image. One house has fallen, but others deserve to also. Wherever the earth extends the avenging furies rule. I:210-243

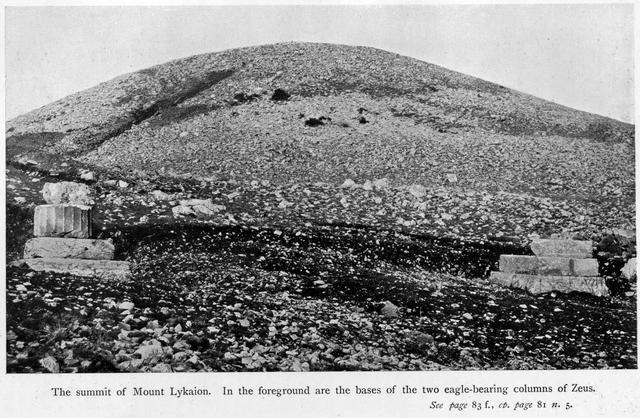

So how does this macabre tale connect to Valentine’s Day? Mount Lykaion (“Wolf Mountain”), the mighty peak in Arcadia where King Lycaon was thought to have been transformed into a wolf, became the site of a secret ritual honoring the “Wolf-Zeus,” during which adolescent boys (epheboi) celebrated the symbolic transformation between wolf and man. Modern archeology has revealed that this mountain was a religious center long before the name Zeus was even known in Greece: in 2008, it was announced that ritual activity dating from 3,000 BCE was evident at the site. The deep history of werewolves, then, pushes back into the Neolithic era.

A photograph of Mount Lykaoin from Arthur Bernard Cook, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion (Cambridge, 1914).

The wolf-rites of Mount Lykaion appear to have been the direct inspiration for the more famous Roman holiday of Lupercalia. This festival, which spanned February 13-15, was a fertility rite intended to purify and protect the city of Rome. The rite centered around the Lupercal, which was supposedly the very cave in which the she-wolf had suckled Romulus and Remus, mythical founders of Rome (as depicted in the famous bronze statue of the ‘Capitoline Wolf’ below):

The Capitoline Wolf in Rome, thought to be an Etruscan bronze of the 5th century BCE. Via Wikimedia Commons

An Italian archeologist announced in 2007 that the remains of the Lupercal were believed to have been found directly beneath the ruins of the palace of the Emperor Augustus.

A 2007 photograph taken by an electronic probe of the lavishly decorated Roman chamber that may be the Lupercal grotto. Via National Geographic

The priests of Lupercalia were the Luperci, or “Brothers of the Wolf,” who Cicero described as “a wild association… both plainly pastoral and savage, whose rustic alliance was formed before civilization and laws” (Cael. 26). These priests were said to smear blood upon the foreheads of the noble youth of Rome and dress them in shaggy wolfskins. The youths were required to laugh, and seem to have gone into a sort of frenzy. The great historian Plutarch noted the connection with the Arcadian Wolf-Zeus ceremonies and added,

At this time many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery, and the barren to pregnancy. Life of Caesar, 61

Now, at last, we approach the reasons why a Bronze Age wolf-ritual was the direct ancestor of our modern commercialized holiday of love. By the fifth century C.E., the Roman Empire was beset by external foes and had become officially Christian. Lupercalia continued to be celebrated by the populace, but it increasingly became an object of concern from the Christian authorities. Pope Gelasius I (492-496) went so far as to write an epistle mocking and condemning the rites, and was ultimately responsible for their suppression on grounds of improper behavior.

14th century French codex depicting Bishop Valentine of Terni (BN, Codex: Français 185, Fol. 210). Via Wikimedia Commons

Yet Gelasius was not truly ending the holiday—only changing it. In 496, the last year of his reign, he announced a new feast day of the martyrs Valentine (two existed, a priest of Rome and a bishop of Terni, of whom virtually nothing certain is known). The date of this feast, February 14, would allow it to replace the pagan holiday of Lupercalia (February 13-15) he had recently denounced.

Valentine’s feast day appears not to have acquired romantic overtones until the 13th or 14th centuries, but this is only based on evidence in written texts. Did the celebration of fertility of the Luperci and Lykaon survive among the common folk, later to be revived as a pseudo-Christian holiday of love? It is impossible to say with any certainty, but given what we know about the submerged survival of ‘pagan’ practices in Late Antiquity and medieval Christianity, it strikes me as probable.

In other words, happy wolf-day, everyone!

This post is adapted from “Happy Lupercalia” which I posted to my history blog Res Obscura on February 15, 2011.