It Starts with an Earthquake

“One peculiar thing is that almost every one thought that the end of the world was at hand.”

—A contemporary account of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

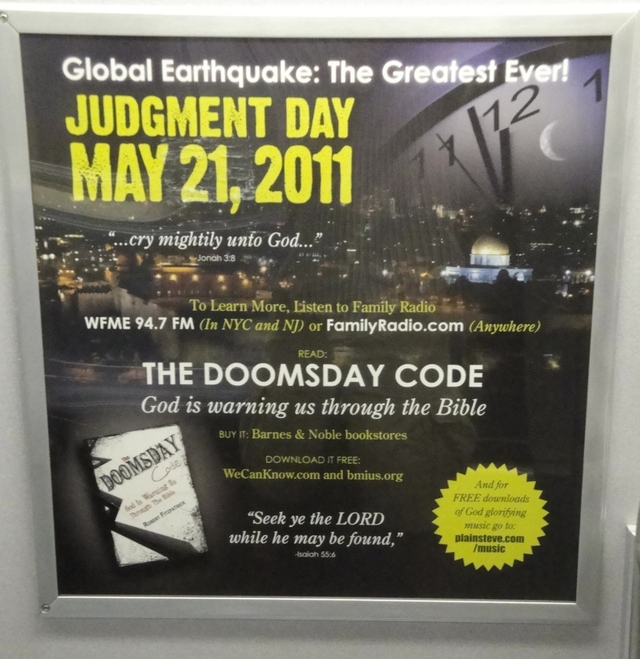

Before the most recently predicted end of the world, there was the failed apocalypse of May 21, 2011, the day on which Harold Camping predicted the arrival of the Rapture according to his personal system of Biblical numerology. Camping, an 89-year old civil engineer and radio evangelist from Oakland, described the anticipated events to a reporter:

When we get to May 21 on the calendar in any city or country in the world, when the clock says about 6 p.m., there’s going to be this tremendous earthquake that’s going to make the last earthquake in Japan seem like nothing in comparison.

According to Camping, the great earthquake would begin at Kiribati (Christmas Island) on the International Date Line, and ripple across the globe time zone by time zone. Camping’s tens of thousands of followers, many of whom quit their jobs and sold their houses in anticipation, would ascend to heaven. Those left behind would endure a period of tribulation amid the rubble until the world itself came to an end on the 21st of October.

A poster announcing Camping’s apocalyptic prediction. By Christopher Paulin, used under Creative Commons license.

The apocalyptic earthquake failed to arrive as scheduled, and Camping withdrew into seclusion. But however unsound his math may have been, his fixation on earthquakes put him in extensive historical company: earthquakes have long been associated with the end of the world in theological and popular imaginations. They appear in a wide range of apocalyptic narratives, from the doomsday prophecies of Camping and Benjamin the Anti-Christ (featured in this issue’s Open Source) to pop culture manifestations like R.E.M. lyrics.

Nor is the association limited to Western monotheistic traditions: in Aztec cosmology, the current world is supposed to end with an earthquake, as the previous ones had ended by floods, fire, and storms. A variety of religious and mythological traditions connect earthquakes with divine anger, portents of doom, and cataclysmic transformations of the universe. As James Wood writes, “a toothache is bad luck; an earthquake is somehow theological.”

Perhaps something about the uncanny sensation of an earthquake—the ground trembling beneath our feet, the built world crumbling around us—invites an eschatological perspective. But the curiously specific prophecies of Camping and Benjamin—who proclaimed that “the great Earthquake will take place, in California, on the 22nd day of February in the year 1871, 14 minutes past 11 O’clock A.M.”—go against the grain of standard Christian eschatology. Indeed, one thing seismology and mainstream theology have in common is an insistence on the limits of our knowledge. Seismic forecasting functions in geological time: patterns of seismic activity are only legible across the span of decades or centuries. We still have no way to accurately predict the time of any earthquake before the shaking starts—though, as with the apocalypse, that doesn’t stop people from looking for signs and portents. But the moment will come without warning: “of that day and hour knoweth no man,” as the Gospel of Matthew puts it.

Earthquakes have always held a special significance in Christian apocalyptic tradition. An earthquake plays a central role in [John’s description]((http://bible.cc/revelation/16-18.htm) of the apocalypse in the Book of Revelation: “And there were voices, and thunders, and lightnings; and there was a great earthquake, such as was not since men were upon the earth, so mighty an earthquake, and so great.” Scholars have suggested that the proliferation of earthquake references in biblical texts may bear some connection to the seismological record of the landscape in which they were written. As John Murray notes, “six of the seven cities to which John’s writing was addressed—Laodicea, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, Smyrna, and Ephesus”—had been hit by earthquakes during the preceding century.

Amos Nur, a Stanford geophysicist, became so convinced that archaeologists were overlooking the impact of seismic activity on ancient sites in the Holy Land that he co-authored a book on the topic—which argues, among other things, that the Revelation earthquake narrative may be a “retrospective prophecy,” the hidden history of a devastating earthquake in the city known as Megiddo: Armageddon. Regardless of whether or not earthquakes can plausibly explain the destruction evident in the archaeological record, Nur’s argument is a pointed reminder that active fault lines cut across much of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Perhaps that’s why Islamic eschatology also has a distinctly seismological flavor. Earthquakes make several appearances in the Qur’an, figuring both as instances of God’s punishment and as premonitions of the Judgment Day. The eponymous earthquake of the ninety-ninth surah, al-Zalzala (“The Earthquake”) is actually the process through which that judgment takes place, with the earth offering its testimony as a sort of material witness:

When the earth is shaken with her (violent) shaking,

And the earth brings forth her burdens,

And man says: What has befallen her?

On that day she shall tell her news,

Because your Lord had inspired her.

On that day men shall come forth in sundry bodies that they may be shown their works.

So he who has done an atom’s weight of good shall see it

And he who has done an atom’s weight of evil shall see it.

As in the Christian context, these scriptural references formed the basis for an interpretive tradition that regarded earthquakes as punishments for worldly sins or as reminders of the coming judgment. The great earthquake that shattered Ottoman Istanbul in 1509 was known as “kiyamet-i suğra,” or “the little apocalypse”—a phrase that is still invoked in discussions of earthquake risk in Istanbul today, and which gave its name (translated into modern Turkish) to a 2006 psychological horror film about earthquake paranoia: Küçük Kiyamet.

In light of these discursive traditions, it’s not surprising that so many historical accounts of earthquakes incorporate references to the apocalypse. William James, in his lively account of the 1906 earthquake, tells of a “lady in a San Francisco hotel” who thought she was witnessing “the end of the world and the beginning of the final judgment….she told me that the theological interpretation had kept fear from her mind, and made her take the shaking calmly.” In the aftermath of the devastating 1999 Marmara earthquake, a pair of Turkish sociologists asked survivors what terms had come to mind during the initial moments of the earthquake, and 37 % of their respondents reported thoughts of kiyamet, or apocalypse. “Dünyanın sonunun geldiğini ve kiyametin koptuğunu düşündüm,” said one: “I thought it was the end of the world and the outbreak of the apocalypse.”

In the course of my own research, I’ve come across such echoes in earthquake stories told by believers and non-believers alike. The language of apocalypse has come to function as a narrative framework through which people experience and seek to make sense of earthquakes. And that apocalyptic perspective, filtered through a secular irreverence, can also provide a way to laugh in the face of danger: consider, for example, the “California Almanac” that Mark Twain wrote shortly after the 1865 San Francisco earthquake, just a few months before Benjamin the Anti-Christ experienced his first apocalyptic vision. Twain pokes fun at both the earthquake fears of ordinary San Franciscans and the calendar-obsessed certainty of would-be prophets, giving a brief and hilarious forecast of seismic and meteorological drama (October 23: “mild, balmy earthquakes”; November 2: “spasmodic but exhilarating earthquakes, accompanied by occasional showers of rain and churches and things”) that comes to a rapid and emphatic end:

November 6 Prepare to shed this mortal coil.

November 7 Shed!

November 8 The sun will rise as usual, perhaps; but if he does, he will doubtless be staggered somewhat to find nothing but a large round hole eight thousand miles in diameter in the place where he saw this world serenely spinning the day before.

Not with a bang, then, but with a quipster.

FURTHER READING:

Akasoy, Anna A. (2007). “Islamic Attitudes to Disasters in the Middle Ages : A Comparison of Earthquakes and Plagues,” The Medieval History Journal 2007 10: 387.

Bein, Amit (2008). “The Istanbul Earthquake of 1894 and Science in the Late Ottoman Empire.” Middle Eastern Studies 44 (6): 909-924.

Cook, David (2002). Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic, Princeton: Darwin Press.

Köse, Ali, and Talip Küçükcan, (2006). Deprem ve Din: Marmara Depremi Üzerine Psiko-Sosyolojik Bir Inceleme (Earthquake and Religion: A Psycho-Sociological Study on the Marmara Earthquake). İstanbul, Emre Yayınları.

Murray, James S (2005). “The Urban Earthquake Imagery and Divine Judgment in John’s Apocalypse,” Novum Testamentum XLVII 2: 142-161.

Nur, Amos and Dawn Burgess (2008). Apocalypse: Earthquakes, Archaeology, and the Wrath of God. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

-medium.jpg)