A cat’s mark on a fifteenth century archival document photographed by Emir O. Filipović.

A cat’s mark on a fifteenth century archival document photographed by Emir O. Filipović.

Of Cats and Manuscripts

It is a pleasant and heartwarming experience to see a photo I took receive so much positive attention from so many people in different parts of the globe. It has now been re-blogged, re-tweeted, shared and commented on so many times that I cannot keep track of it all, and the story has been covered in English, Russian, Japanese, Greek, Romanian, French, Hebrew, to name just the ones that I saw.

But why could a simple photo of cat paw prints on a medieval manuscript become so popular on the Internet? Do manuscripts and felines make a good combination, or can this popularity be ascribed to the fact that many contemporary cat owners identify themselves with the unfortunate medieval scribe? I cannot give a straightforward answer to these questions because it is clear to me that there is no formula or recipe for determining whether anything on the Internet will become a success or not. Despite the obvious power of social networks, blogs, and the Internet in general, I still could not ever have thought that one of my photographs would become so coveted, especially since I did not intentionally seek the exposure it received.

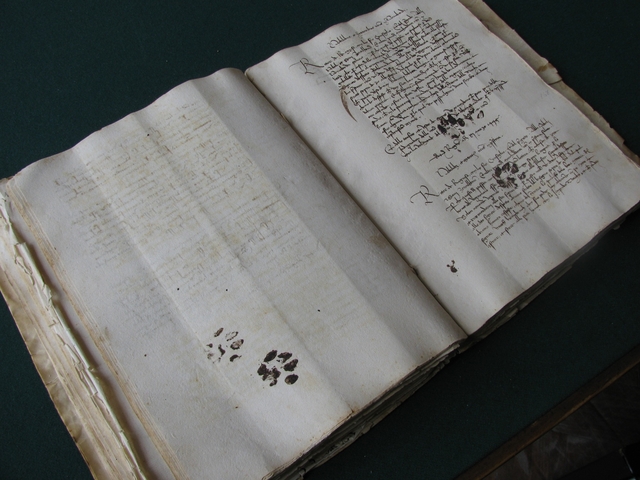

The pawprints, which went viral on Twitter and were featured on Gawker and the Atlantic. Via the Dubrovnik State Archives. Photograph by Emir O. Filipović.

My story line follows a simple path: I was doing some research in the Dubrovnik State Archives for my PhD, I came across some pages which were stained with cat paw prints, I took a few photos of this (as I do whenever I notice something interesting or unusual on any old book I’m reading), and carried on with my work not paying too much attention to something which at that time could essentially be only a distraction. I never had any kind of intention of publishing or doing anything else with those photos apart from showing them to my colleagues for the sake of amusement.

When the book historian Erik Kwakkel tweeted an illumination of an angry cat in a medieval manuscript, I thought that he and his followers might be interested in seeing my photo. He re-tweeted it, people liked it, and that was pretty much all there was to it. That is until a famous veterinarian published the same photo on his Facebook page, where it received so much attention that people started writing to me enquiring about the provenance of the manuscript and other details that they wanted to include in their posts about the cat prints.

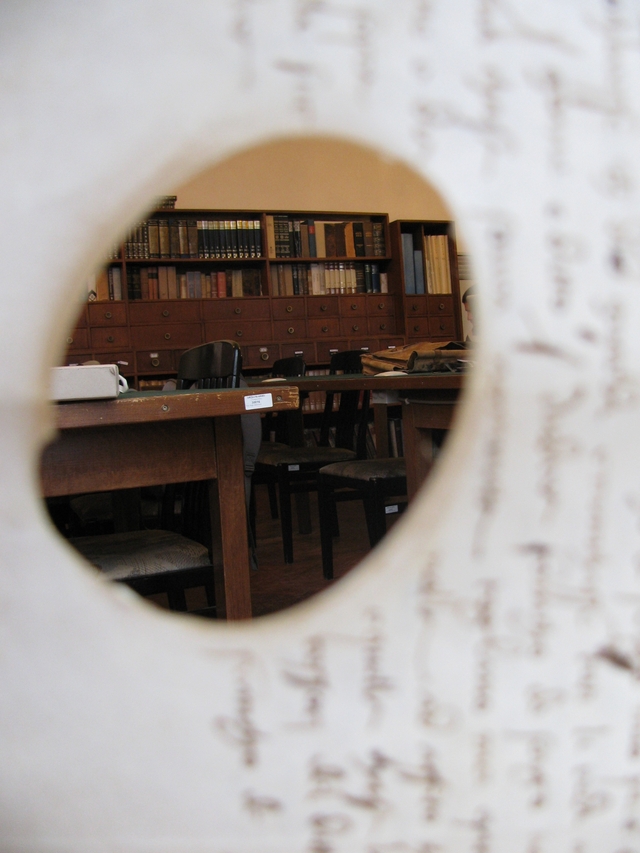

After a couple of days the enthusiasm waned and people stopped contacting me with questions about the photo. However, a truly positive aspect of the story, beside the obvious worldwide promotion of the State Archives of Dubrovnik, is that the document with the paw prints is going to be featured in the Interactive Album of Medieval Paleography, which is maintained by Dr. Marjorie Burghart in Lyon, France. This will, hopefully, allow students and other medieval historians to familiarize themselves with the kind of documents which I have been working on during these last couple of years. Apart from that, another advantage of the photo is that I got an opportunity to share the other interesting bits and pieces I found in Dubrovnik/Ragusa, a truly remarkable place on the eastern coast of the Adriatic.

For those unfamiliar with the history of Dubrovnik, it is perhaps most important to say that in the Middle Ages it was a commune governed by the local aristocracy and that one of the main aspects of its medieval economy was seafaring trade. Owing to its strategic location Dubrovnik was ideally placed to connect the rough Balkan hinterland with all the other places that lay across the sea, exchanging goods, knowledge and experience in the process. As is the case with all businessmen, the inhabitants of Dubrovnik liked to record their actions and a notary and archives were set up in the second half of the thirteenth century with that goal in mind.

The fact that this commune maintained its independence as a free state (despite recognizing Venetian, Hungarian, and Ottoman authority during different periods in its history) until the beginning of the nineteenth century meant that the records of its archives were spared and they now represent one of the best sources for studying all kinds of medieval and early modern topics. In fact, the medieval Mediterranean comes alive in the Dubrovnik Archives. The sources we find there give us a picture of a bustling port town full of activity, with different people coming from different places to engage in various commercial or legal activities. The famous historian Fernand Braudel wrote that the Dubrovnik Archives were “far and away the most valuable for our knowledge of the Mediterranean … To anyone with the time and patience to study the voluminous Acta Consiliorum, they afford an opportunity to observe the extraordinarily well-preserved spectacle of a medieval town in action. For reasons of registration or through legal disputes an amazing collection of documents has survived.”

In this multitude of documents, archival registers and books, a researcher can come across information relevant to countless different aspects of life in the Middle Ages. Apart from the interesting written sources, one can also encounter the little traces which medieval people left in the manuscripts preserving them for posterity. They are rare and curious and it is refreshing when you come across something like them while conducting research. These things are noteworthy because they offer a stark contrast to the rest of the archival register, which can sometimes contain monotonous and unexciting texts, like the record of debts or division of land. Such personalized marks give us the chance to feel a more personal connection with the individual involved in the creation of the document, or even with the person who handled it in later times. You can connect with the past much more directly by identifying yourself with the writer of the text, by placing yourself in his position, or imagining what he must have been thinking about while leaving his trace in the book.

The photo of the cat paw prints represents one such situation which forces the historian to take his eyes from the text for a moment, to pause and to recreate in his mind the incident when a cat, presumably owned by the scribe, pounced first on the ink container and then on the book, branding it for the ensuing centuries. You can almost picture the writer shooing the cat in a panicky fashion while trying to remove it from his desk. Despite his best efforts the damage was already complete and there was nothing else he could have done but turn a new leaf and continue his job. In that way this little episode was ‘archived’ in history.

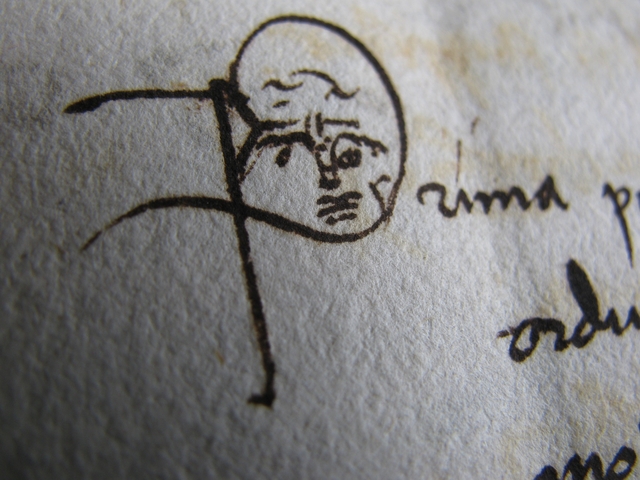

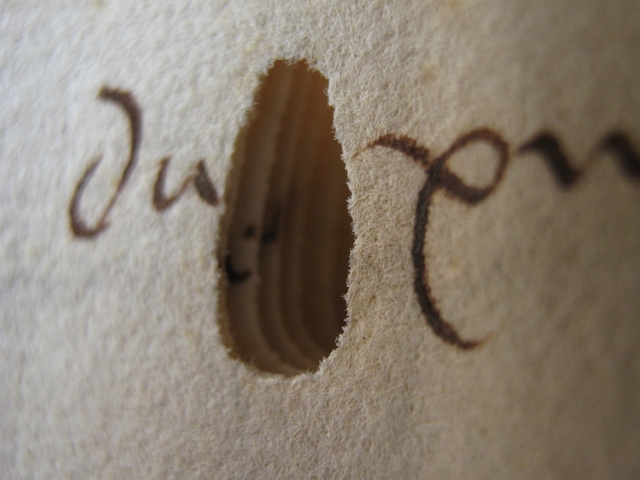

But there are other similar instances when you feel compelled to think about people (or indeed animals) involved in the creation of historical documents. In one case, in the minutes of a council meeting, I noticed the scribe became tired as the meeting went on, his writing growing more garbled and sloppy as the day progressed. On other occasions I came across the doodles and drawings of a bored notary, who scribbled them while waiting for his next assignment, or just to show that he possessed more skills than just pretty writing alone. The same can be said of the beautifully decorated initials that one associates with the richly illuminated medieval manuscripts, but which pop up in the records every now and then. They often look out of place in the strict and formal context of the archival book. There are also times when one can find natural holes in the vellum and see how the writer attempted to work his text around it. And perhaps we should also spare a thought about the bookworms who made holes of their own in the manuscripts.

A natural hole in fifteenth-century vellum. Via the Dubrovnik State Archives. Photograph by Emir O. Filipović.

Most notaries and scribes of the Middle Ages weren’t only skilled in writing, they were well educated and possessed a significant amount of general knowledge. Sometimes they wanted to demonstrate this and one such example is recorded on the back pages of an archival book where the notary wrote down an excerpt from Ovid’s Metamorphoses:

Pronaque cum spectent animantia cetera terram

Os homini sublime dedit celumque videre

Jussit et errectos ad sidera tollere vultus

Ovid, Met. 1.84-86

Whereas other animals look grovelling at the ground,

to man he gave an upturned aspect, and ordered him to look

at the sky, and to raise his face to the stars.

What motivated the writer to jot down this rather famous quote about the creation of man? Was there something specific which inspired him to do so? Did he want to express his knowledge of classical authors? Was he fed up with being told what to write, and, in a sense, protesting against this? Or was he tired of continually bowing his head to look down at books, and thus remembered a quote about gazing at the stars?

Or, he could have only been trying out a new quill.