Photographs, Landscape and Memory

“Landscape,” British historian Simon Schama writes, “is the work of the mind. Its scenery is built up as much from the strata of memory as from layers of rock.”

Living in an old quarter of Lisbon for much of the previous year, I often reflected on this relationship between landscape and memory. The castle I saw on my daily walk to the metro had been seen from the same vantage point by the eyes of Vasco de Gama, Lord Byron and Mussolini. In the earth beneath the castle, visitors can gaze down archeological shafts through the collapsed roofs of the partially excavated Roman city of Olisipo. Deeper still, the bricks, bones, and amphora of the Carthaginians who first built the city, and below that, Neolithic remnants: shards of antler and flint. All testaments to the forgotten lives of individual humans. They had seen the same periwinkle blue estuary of the River Tagus, walked the same granite-strewn hills.

But as the famously cryptic Greek philosopher Heraclitus put it, “We both step and do not step in the same rivers. We are and are not.” Landscapes offer an impression of permanence, but they are as much in flux as the contents of our own memories. Regenerated each spring, continually reshaped by earthquakes, exposure, sedimentation, and human activity, a landscape is both constant and constantly changing – just as our own bodies recreate themselves, sloughing off molecules and generating new ones at such a rapid clip that it is estimated that we replace most of our cells every decade or so.

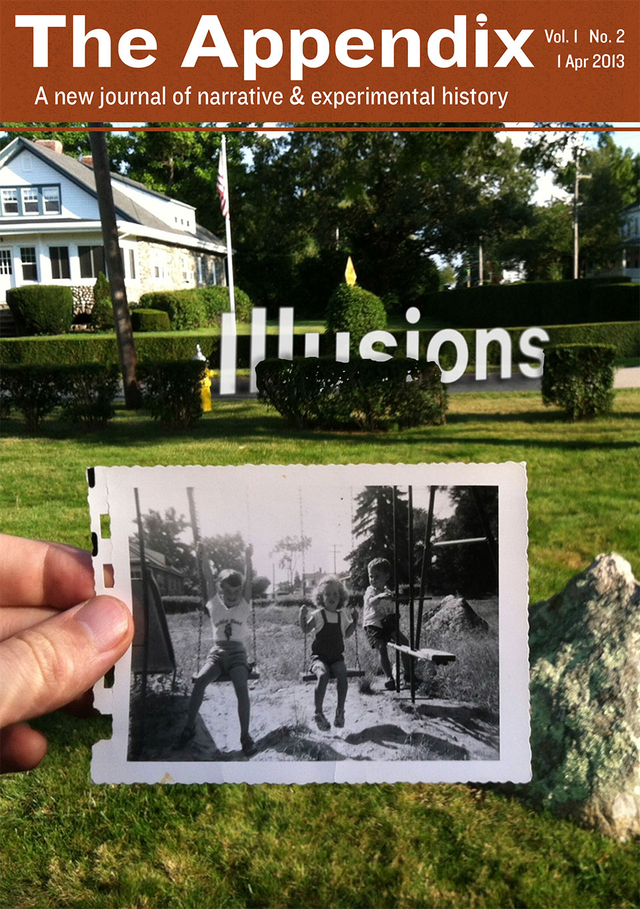

When we at The Appendix started thinking about the theme of “Illusions” for our second issue, we decided to construe the term as broadly as possible. We wanted it to encompass magic tricks, deceit, forgery and lies, but also deeper illusions: illusions of permanence; illusions created by our own memories. For the cover of The Appendix Issue Two, we settled on a photograph-within-a-photograph depicting the same spot of ground in 2012 and circa 1960. The hand in the photo is mine as an adult; the photograph I’m holding shows my father and his sisters as children. Photographs are famously susceptible to trickery and hoaxes. Photography is also, as Susan Sontag noted, a process of metamorphosis that turns a moment in time into a frozen object, transforming “an event or person into something that can be possessed.”

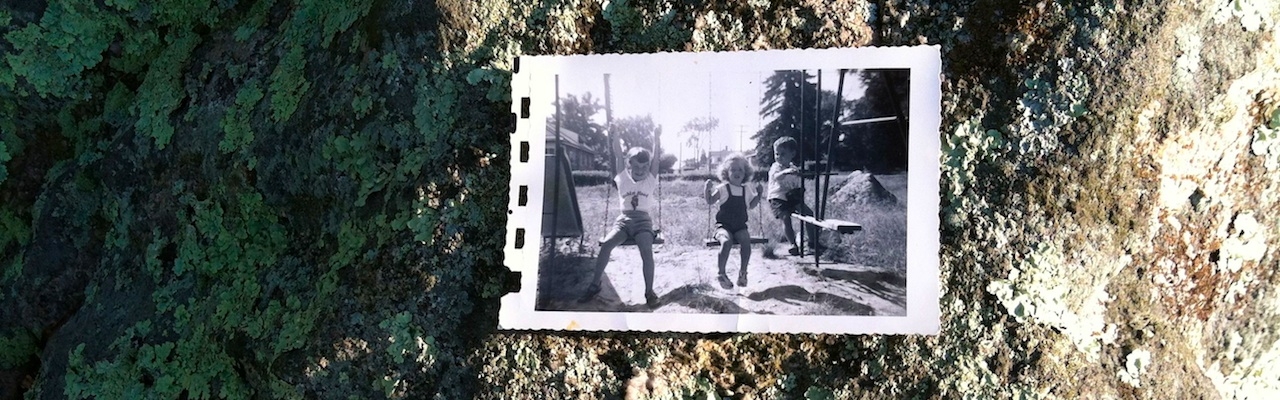

In other words, photographs, like landscapes, create an illusion of permanence. The images below are others in the series that gave rise to our Issue Two cover. I took them with an iPhone camera in the summer of 2012 while visiting my deceased grandmother’s old house in Scituate, a largely Irish-American seacoast town south of Boston. While going through her family photo albums, I realized that many had been taken in locations that I still recognized decades later. But in contrasting these old photos with their present-day correlates, it was the differences between the two scenes that struck me. The juxtaposition reminded me of the novelist L.P. Hartley’s oft-quoted observation that “the past is a foreign country.”

Photographs are passports.

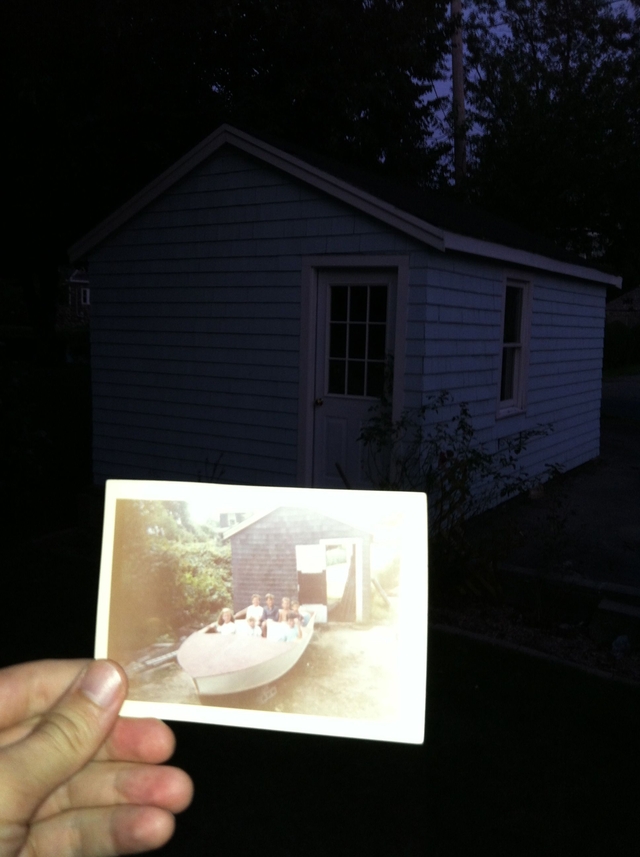

The shingles of my grandmother’s house juxtaposed with a photo of it from the 1950s, when it belonged to her mother-in-law, visible in the photo. Benjamin Breen, 2012

My grandmother on her way to Mass. The stop sign and boulder offer points of reference bridging the two scenes across time. Benjamin Breen, 2012

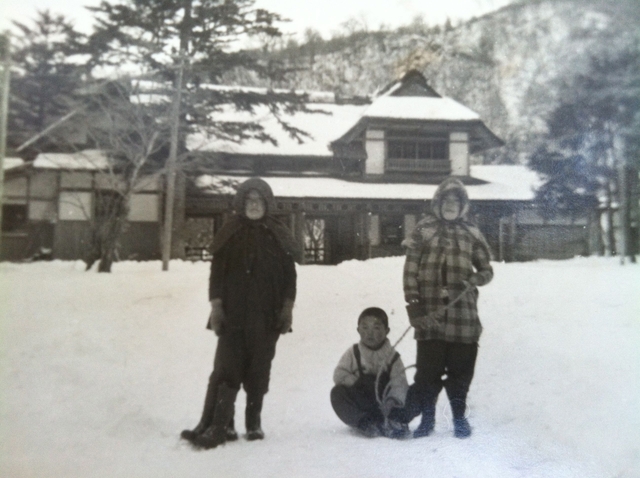

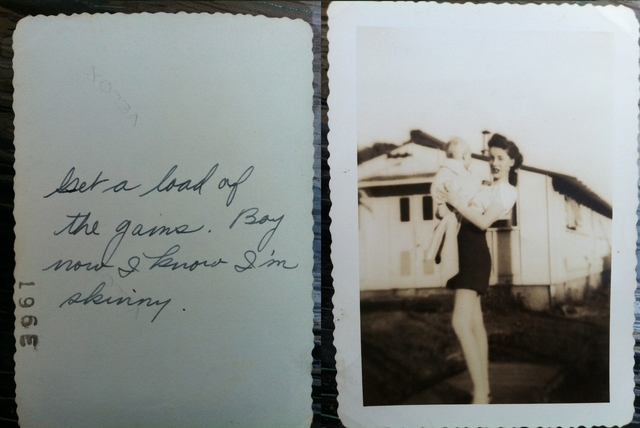

A 1940s family photo, with a note on the back: “Get a load of the gams. Boy now I know I’m skinny.” Benjamin Breen, 2012

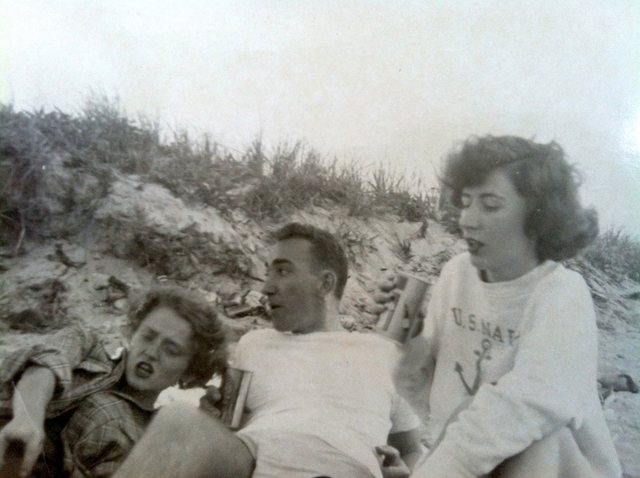

I couldn’t identify the people in this photo, but another from the same series shows my grandfather, evidently fresh out of the Navy. The post-World War 2 feeling here reminds me a bit of the recent P.T. Anderson film The Master. Note the crumpled beer cans piled in the sand behind them. Benjamin Breen, 2012