An early Dianetics seminar in 1950.

An early Dianetics seminar in 1950.

Cops and Robbers: Why the Church of Scientology Hated Interpol

When I began my dissertation research into the origins of the multinational crime fighting organization Interpol, I encountered a number of very good histories written by retired police officers, historians, and sociologists. I also found a number of works based on wild conjecture. This sort of discovery is par for the course when studying a security or surveillance organization, but what made these books about Interpol stand out was that they were published by the Church of Scientology in the 1970s. These COS books attack Interpol (playing up, in particular, the group’s Nazi period), but provide no explanation for why the Church set their sights on the organization in the first place. Was this literature inspired by general post-Watergate paranoia, or did some particular event set it off?

L. Ron Hubbard moved Scientology’s headquarters to Sussex, England in 1960—ostensibly to spread the religion but also to avoid an impending investigation by the United States government on the basis of tax evasion. Hubbard had previous connections, of a sort, to England, having been a leading member of the California branch of the Ordo Templo Orientalis, an offshoot of the Order of the Golden Dawn controlled by Aleister Crowley. Hubbard’s expulsion from the group for embezzlement was followed shortly thereafter by the publication of Dianetics, a theoretical work that forms the basis of the Church of Scientology.

Audience members watching L. Ron Hubbard conduct a Dianetics seminar in Los Angeles, 1950. Wikimedia Commons

Hubbard lived in London on and off during the 1950s, but took up permanent residence in England at Saint Hill Manor, Sussex in 1959. From its new headquarters in the United Kingdom, the Church began to spread into continental Europe. In 1968, West German police, concerned about the opening of Scientology auditing centers in their country, requested information on the organization from Interpol. Interpol had yet to create a dossier on the Church, and thus asked the London Metropolitan Police (the Met) to develop one.

The Met, using their own surveillance records as well as reports collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), finished this profile on Scientology in 1969, after which it was circulated to Interpol member nations. The Met’s profile portrayed the Church as an organization that used the trappings of religion to avoid taxation on what was essentially a massive confidence scam. The report described the Church’s auditing process as essentially a brain-washing technique that primed the potential member for financial exploitation. As the report details, “the organization caters to the inadequate. The promise of enhanced mental awareness appears to appeal to those already affected by mental instability, unhappiness and uncertainty.”

In the eyes of the Met, the Church’s auditing process was little more than a street level confidence trick, referring to the Church’s auditing machine, “the E-meter,” as nothing more than

a electric meter held in a wooden box [that] has two terminals each of which is attached at the end of a electrode which is a steel or tin can resembling and sometimes actually being, a soup can…The E-meter would appear to be no more than a powerful gimmick for controlling [initiates] and developing in them a sense of awe and submission to a dependency upon the organization.

The report ended with a note of warning:

the authorities in this country are extremely concerned about the organization…scientology is socially harmful; it alienates members of families from each other and attributes squalid and disgraceful motives to all who oppose it. Its authoritarian principles and practices are a potential menace to the personality and well-being of those so deluded as to become its followers.

The Church, well aware of its negative perception among national governments, had established an internal security bureau, referred to as the Guardian’s Office, in 1966 under the leadership of L. Ron Hubbard’s wife Mary Sue. Though it was designed primarily to police members of the Church, the Guardian’s Office also administered counter-surveillance projects. Beginning in the 1970s, the Guardian’s Office planted Church members as employees in several “enemy organizations,” most notably the American Medical Association, the Better Business Bureau, and the Internal Revenue Service, as well as several equivalent bodies in foreign countries. This initiative, codenamed Operation Snow White, led to the theft and destruction of hundreds of thousands of government documents relating to the Church of Scientology before it was discovered by the US government in 1977.

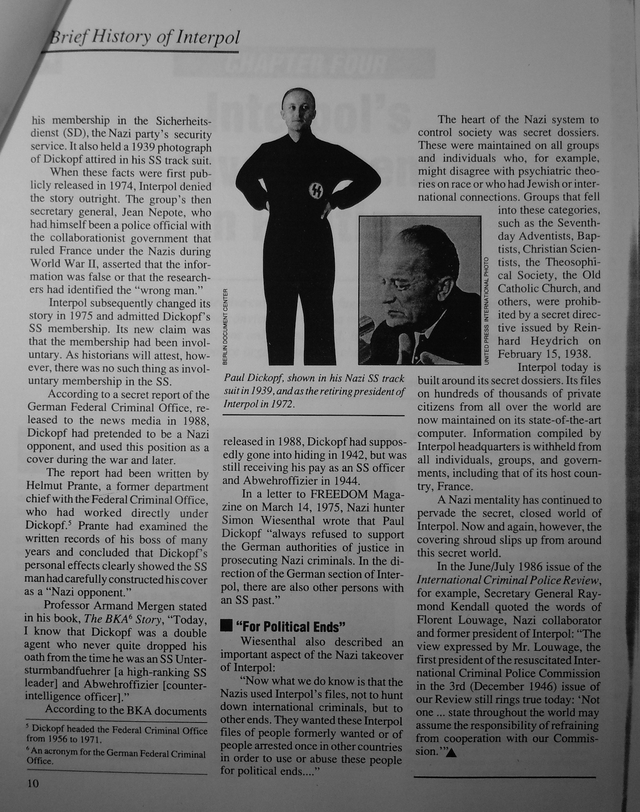

Though I have not been able to confirm it, it is more than likely that this operation, or a similar one, also resulted in the public release of the Met’s profile of the Church of Scientology in West Germany in 1973. The release of this damning document led to a swift response by the Church, which filed suit against Interpol and the Metropolitan Police in German court. The Church followed this by organizing a propaganda campaign against Interpol that attacked it as a tool of totalitarianism, emphasizing in particular the organization’s Nazi past. The early wave of this attack featured short newspaper articles and pamphlets that offered surviving photographs of Nazi-run Interpol conferences during the Second World War.

A page from the 1990 pamphlet, "Interpol: Private Group, Public Menace." Perry-Castañeda Library, University of Texas at Austin

Subsequent attacks became more sophisticated, coming in the form of nonfiction publications that claimed to provide an unbiased discussion of Interpol’s historical and contemporary operation. In his 1976 book, The Secret World of Interpol, author Omar Garrison argued that Interpol maintains an “Orwellian dream” of establishing “a dossier-based dictatorship” that will bring an end to civil liberties around the world. In a more measured approach, authors Trevor Meldal- Johnsen and Vaughn Young (who famously went on to testify against COS) wrote that Interpol had the opportunity to become an effective organization, but it must first curb its despotic lust for information and surveillance of ordinary civilians.

Scientology’s attack on Interpol could not have come at a worse time for the police group. The 1970s began with a drawn-out debate in the United Nations concerning Interpol’s status as an official NGO. This was followed by Senate hearings in the United States in 1976 and 1978—partly inspired by Scientologist propaganda—that questioned the legality of Interpol’s operation as well as its benefits for America.

Interpol, led by Secretary General Jean Népote, attempted to fight back by opening its doors to a new series of investigators including Michael Fooner, Iris Noble, Peter Lee, and Fenton Bresler. These writers helped to counter some of the more extreme arguments emanating from the Church of Scientology. What began as a propaganda assault ended with serious journalism and scholarship.

It is difficult, particularly in the twentieth century, to find a historical event that worked out for everyone involved, but the release of the Met’s report seems to be one of those instances. Despite a bit of handwringing, Interpol passed through hearings in the United States and at the United Nations largely unscathed, and remains the preeminent international organization for criminal justice. Yet the event also gave the Church of Scientology a powerful persecution narrative to attract new converts and to strengthen the resolve of devotees. Whether this was a good or bad development, I leave for the reader to decide.

Finally, historians were left with an interesting interlude that encourages further research. When it comes to the writing of history, sometimes the wrong turns are the most useful.