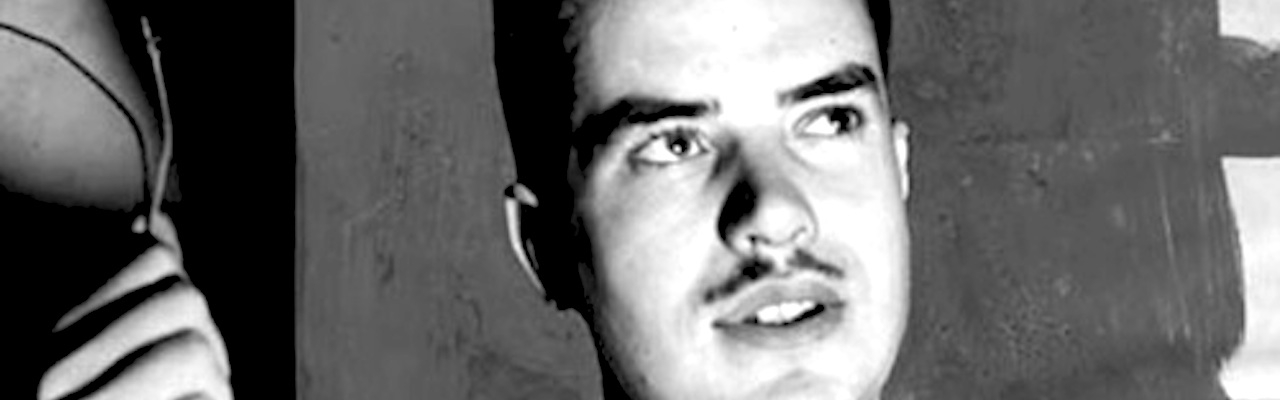

Jack Parsons in the early 1940s.

Jack Parsons in the early 1940s.

Magic Isn’t Rocket Science

Every spring, residents of Pasadena, California confront a phenomenon they call ‘June Gloom’: the sunny climate of this idyllic, wealthy town east of Los Angeles grows uncharacteristically dark. Oppressive cirrus clouds the color of TV static blow in off the Pacific, and misty rains buffets the leaded glass windows of vine-clad Victorians. During the late night fogs, avenues of whispering palms glow under antique streetlamps. On clearer nights, the moon gazes down from its perch above the austere, almost Martian peaks of the San Gabriels. The uncanny nature of the place comes to life.

“I had to run home last night,” a friend told me recently, “There was something frightening about the streets. It gave me the shivers.” Her street is absurdly safe, home to rows of Tuscan-style villas housing older, well-heeled families, but I knew what she meant. There is something about the place, a feeling of strangeness concealed. And there’s a reason for this. Pasadena, home of the world’s top-ranked science university (Caltech) and the elite facility that controls NASA’s Mars rovers (the Jet Propulsion Lab) has also been home to a distinctly twentieth-century form of magical occultism.

And surprisingly, the rocket science and the black magic sprang from the same source.

I knew nothing of this history until the month before I moved to Pasadena to take up a fellowship at the Huntington Library, a palatial compound of interlocking gardens and villas created by the Gilded Age railroad tycoon of the same name. I was curious why the Huntington, the Jet Propulsion Lab, and Caltech had all emerged in the same sleepy suburb of Los Angeles. Did they share a common history?

It soon emerged that Pasadena’s early history was much like that of the rest of Anglo LA: as the movie Chinatown (1974) brilliantly evoked, competing forces came together, sometimes violently, to build a vast metropolis out of a desert in the early twentieth century. They siphoned water from the ravines of the scrubland, but more importantly they siphoned American optimism. They created an Emerald City in the American west, a place that was a simulacrum of itself: a city that played itself in the movies.

Pasadena is a slice of this story. After the United States seized California from Mexico, waves of wealthy settlers from the American Midwest moved to the small town, drawn by its accessibility via railway. It became a resort town, famed for its lavish hotels, craftsman houses, and, before long, its intellectual community. A solar astronomer named George Ellery Hale had been attracted to the region by the clear skies, founding the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1904. Soon a nucleus of scientists developed, bolstered by Albert Einstein who spent 1931 working on his Theory of General Relativity in a quiet bungalow near Caltech. The United States government became increasingly interested in the military potential of this massed scientific talent, and began to fund secret experiments involving chemical explosives, rocketry, and experimental physics.

This was the world that a striking-looking twenty-two year old college dropout named Jack Parsons encountered when he took a job with the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory in 1936. Parsons, the scion of a wealthy but troubled southern California family, was a self-taught chemist who worked through a process of mystical intuition. Together with the Caltech scientist Frank Malina and a mechanic named Ed Forman, Parsons formed a group that NASA calls the original “rocket boys”:

They scraped together cheap engine parts, and on 31 Oct. 1936, drove to an isolated area called the Arroyo Seco at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains. Four times that day they tried to test fire their small rocket motor. On the last attempt, they accidentally set fire to their oxygen line, which whipped around shooting fire. These were the first rocket experiments in the history of JPL.

In 1941, at a crucial moment in the arms race between the Allies and Axis powers, Parsons had a brilliant insight which led to the development of modern rocketry. Following his intuition, Parsons claimed, he struck on the combination of potassium perchlorate and common roofing tar as components in solid rocket fuel. The technology would later make possible both intercontinental nuclear missiles and the Apollo moon landing.

Parsons (right foreground), Malina and their team at an early rocket test near Pasadena in 1936. Courtesy of NASA/JPL

Strikingly, however, Parsons appears to have conceived of his work almost as an offshoot of early modern alchemy, regarding his insights as deriving from mystical sources. Around the time of his greatest creativity as a scientist, Parsons was becoming immersed in the world of Los Angeles occultism. He quickly became a leader of the Agape Lodge, the west coast branch of the English magus Aleister Crowley’s Ordo Templo Orientalis, itself an offshoot of the famed Victorian occult group the Order of the Golden Dawn. In December of 1940, a member of the Lodge recorded in her “Magical Record” that Parsons, “a newcomer,” had “begun astral travels.” Just four months later, the lodge’s leader, Wilfred Smith, was writing to Crowley that

I think I have at long last a really excellent man, John Parsons. And starting next Tuesday he begins a course of talks with a view to enlarging our scope. He has an excellent mind and much better intellect then myself… John Parsons is going to be valuable.

Crowley soon became convinced of Parsons’ potential as an occult leader—but by the late 1940s, he had grown disappointed by what he regarded as the American scientist’s overly enthusiastic nature. Parsons had by this time become obsessed with the idea of performing magical rituals which would give material form to a spiritual being which he called an “elemental.” To his well-heeled neighbors’ dismay, he had also converted his sprawling Pasadena mansion into an enclave of bohemian writers and fellow mystics (in the undated photo below, Parsons poses with Smith and Regina Kahl, the leaders of Agape Lodge).

Parsons’ closest friend during this period was an ex-Navy officer with a shadowy past: L. Ron Hubbard. Before long, the future founder of Scientology had seduced Parsons’ young wife and embroiled him in a dubious business venture involving the purchase of East Asian yachts, but Parsons was unphased. “I need a magical partner,” he wrote of Hubbard. “I have many experiments in mind.”

Parsons’ life ended in tragedy: in 1951, he accidentally killed himself during one his chemical experiments by dropping a highly explosive substance called fulminate of mercury. By the time of his death, the world of high technology had already passed him by. While his peers at Caltech were helping develop nuclear weapons and space flight, he had been reduced to creating special effects for Hollywood films.

Parsons’ legacy, however, is all around us. The strange union between mysticism and technology that Parsons represented is woven into the fabric of twenty-first century life. In a future Appendix article, I intend to draw out what I mean by this. Although Parsons was (from my skeptical perspective) deluding himself with illusions of magical skill, he was indeed the possessor of a formidable power: technology.

Parsons and his fellow magical acolytes believed that in the twentieth century the human race had entered a new, forward-looking era they called the age of Horus. “The Aeon of Horus,” Parsons wrote, “is of the nature of a child… perfectly ruthless, containing all possibilities.” But that childlike nature, he believed, “is also the nature of force—blind, terrible, unlimited force.”

Writing, as he did in the era of the atom bomb, I can’t say he was wrong.