Landscapes of Possibility

The Appendix editors were enamored of Dual Horizon’s suggestion of places out of time and of imaginary landscapes as a canvas for possible worlds and knew it would be a great fit to accompany Matthew Gildner’s contribution to our April 2013 issue, “Andean Atlantis: Race, Science and the Nazi Occult in Bolivia.” The artist, Justin Berry, was kind enough to explore his process and perspective with us. We hope you enjoy this tour of the spaces his landscapes create and remember to check out yesterday’s article which this piece accompanied.

A work like Dual Horizon usually begins by shopping. When I go to the various used bookstores and sidewalk stalls that I frequent I am not looking for books, but for places. It is about the worlds in which these tales take place rather than the stories themselves.

I choose fantasy and science fiction novels because the worlds that interest me are ones of possibility and potential rather than fact. By painting over all the specific signifiers that define a world, such as the lightning-breathing dragons or the time-traveling cyborgs, I make them into containers for new potential worlds.

The landscapes in my images are often exotic, with strange vegetation or odd outcroppings of rock, but they are also very ordinary and frequently a little banal. I like seeing an ordinary world, much like our own, knowing that anything imaginable could exist within it.

In a work of historical fiction we understand the characters to be false, but believe the depiction of an era or a series of events to be authentic. On the other hand, fantasy empowers us, because it allows us to dismiss its assertions and to deny anything it claims. Any truth that we take away is our own. Imaginary worlds are where we determine not what is true or false, but what is possible.

I scan the book covers at an extremely high resolution, making each dot of ink and every fiber of the paper visible. The difference between a scanner and a camera is that the camera composes the image; it defines an angle by which the image is seen. With a photograph there is always a specific relationship between the observer and the thing observed: it is positioned or lit or cropped or otherwise framed from the perspective of the photographer. The scanner is different. It does not acknowledge the thing it sees; it simply records it, a mute witness to the object placed on the scanner bed. With much of my work I am interested in presenting possibilities rather than points of view, and the scanner has no point of view. It removes my hand and eye from the process.

A nun on a bus gazed at me through a mirror and it stung. She was sitting in front of me as I unconsciously rubbed my knee against the back of her seat. She pulled her compact mirror out of her pocket and looked at me through it. I naturally assumed that she was looking at someone else, because I was unaware of any reason for her to look at me. The gesture, in its oddness, made me uncomfortable nonetheless. Then she began to speak to me, still looking at me through the mirror. She accused me of kicking her on purpose. She kept staring.

When we take a photograph it is an aggressive form of looking. It sounds silly to think of simply looking at something as a form of aggression, but this recent experience convinced me otherwise. By using the compact as an intermediary she ultimately controlled my ability to return her gaze, so that I could only see as much of her as she allowed. In framing my view she placed me under her control. Ultimately, when she refused to stop staring at me I had to move.

The point is that we tend to ignore the passive gaze, because it passes over us, while the active gaze threatens us as it forces us to see ourselves from the perspective of another, and perhaps demands that we conform to their expectations When we control someone’s vision we are controlling his or her perspective A photograph uniquely crystalizes that act of looking; making it into something that can be held in the hand. A photograph instructs. I make objects that are photographs, but I use devices other than cameras because they give me greater control over this dynamic—the way a scanner removes me from the exchange or screen captures introduce my gaze into a site where it is normally absent, such as a video game. I want to make photographs that give control back to the viewer by asking them to see what they want within the frame I have constructed.

My intervention with the image begins when I paint over elements of the original cover. I sometimes find it easier to describe this process to others as erasure, to say that I ‘remove’ or ‘erase’ certain things, but that is not the truth. What I am actually doing, though, is layering pieces of the surrounding imagery over the image. The content that I choose to cover up is always the most important to the intent of the original image: the characters, the buildings, and the text. I cover these things up with the landscape behind them. They disappear.

The artist Paul Pfeiffer uses the same technique and he describes it as a kind of camouflage where the original content is disguised, but I think of it differently. Camouflage implies an emphasis on the thing that is hidden, because it is the subject of secrecy. The emphasis is on the missing, rather than the visible. In my intervention I bring the background forward, changing the context into the content. I want to draw attention to what would have otherwise been unseen, not because it was invisible, but because it did not appear to be important enough to notice.

When we look at traditional landscapes they are not empty images. Usually they are ways for the artist to describe how they see the world, whether politically, spiritually, or economically. They convey something. We see this in the Romantic painting tradition where landscapes convey the power and will of God, or in the photography of Ansel Adams where the images contain a veneration of the natural world. The landscapes in my images are different, because they were originally meant to be in the background, to set the mood, or to convey vague otherness. They are not composed; in becoming separate from that which they were designed to frame they take on the sensibility of a snapshot. They become oddly and compellingly purposeless. It makes me think of a still captured by a security camera when the store is closed or nobody is doing anything wrong. It is a picture of possibility.

In my images I always leave the edges of the book intact. It is important that it is a book and not an isolated painting or drawing, that the image is tied to an object which occupies space. I retain all of the scrapes and bruises that the object has accrued, the creases and tears from years of readership or unkind storage. These creases and tears are ruptures that break up the image plane

Books, even as newer media begin to displace them, still signify content and meaning in a way that electronic media does not. A book in its physicality must to be published, implying a kind of authority bestowed through approval or curation. A book offers a promise of information—that to look inside is to find something there. When the cover of a book has been emptied of implied narrative it becomes a different kind of promise, one that is uncertain and depends on the observer rather than on the illustrator or author.

It is important to me that these images are emptied of overt content because it creates alternatives to the media saturation that we experience on a daily basis. Constantly seduced by imagery, our experience of the world becomes deeper when we engage something that doesn’t have anything to sell. Imagine meeting someone on a trip, who doesn’t work with you or live near you or share any of your friends, with whom you can unreservedly share your feelings and become an amalgamation of both who you are and who you want to be, without the anxiety of needing to perform this feat on a daily basis. I don’t think of these images as being instructive or useful; I see them as a gift, a breath of fresh air in a world otherwise polluted by agendas and ideologies.

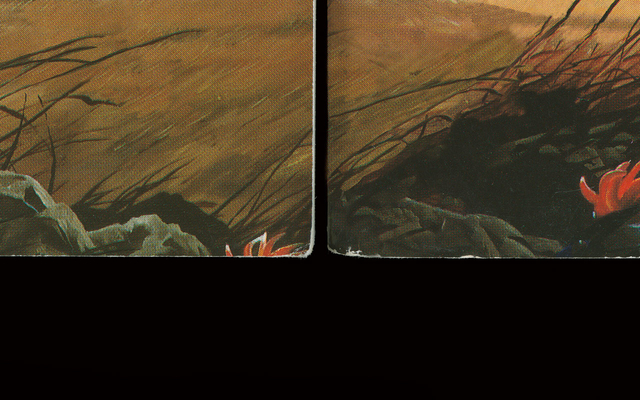

Dual Horizon was the first time I used two copies of the same book side by side, presenting two versions of the same world. I did not try to match the gestures from one side to other; I let each one be unique. The worlds are connected to each other through the horizon line, and there are gestures that intentionally tie them together, such as a blade of grass crossing over both books as if the space between them did not exist. These bridges connect the spaces while other breaks in their continuity make the two worlds uneasy neighbors, reflecting into one another but never truly touching, in an effect similar to a mise en abyme.

Having the two versions side-by-side is an admission of mutual inauthenticity, that neither side is authoritative. The dual pictures record the passage of time, perhaps no more than a few seconds, but enough to animate the static space and bring it to life. The image creates a new kind of stereo-scopicity, so that by crossing and unfocusing ones’ eyes a central image is formed, defined not by depth but by difference, as the various discrepancies hover and tremble within your gaze across this spatial and temporal divide.

If any part of the image is authoritative it is in that combined view, where the right eye and left eye disagree over what they see and the world presented by the photograph is left in flux.