Free Cuba: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial Havana

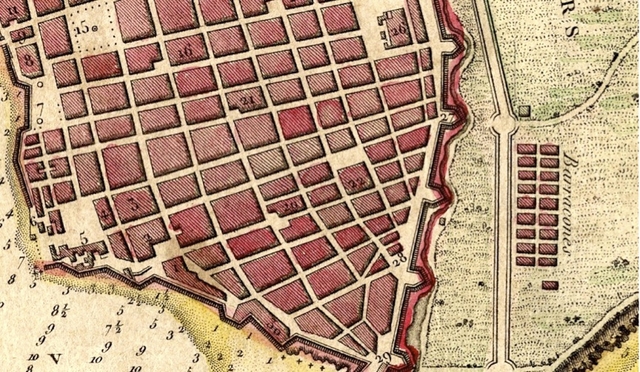

The squares sit neatly in two rows. Cursive lettering labels them barracones, or barracks. They appear on a 1798 map of Havana, located just outside of the city’s walls. Inside the walls, curved streets form the blocks where Havana’s elites resided. Enslaved individuals brought to Cuba (mostly) from Africa waited in these barracks until they were bought or sold to work on plantations or in urban areas. The city walls, along with an impressive fortress system, sheltered the city from outside attack and separated the elite space inside from the less desirable area that lay beyond.

Conditions in the barracks, of course, could not have been less desirable. In the 1810s, a visiting doctor named J.L.F de Madrid witnessed “a number of dying blacks naked and spread out on wooden planks, many of them reduced to skin and bones, and inhaling an intolerable stench.”

In 1791, slaves and free people of color led major revolts in neighboring Saint Domingue that became what we know now as the Haitian Revolution. Internal struggle ultimately led to the collapse of its robust sugar industry, and Saint Domingue ceded its position as the world’s number one producer of sugar. Cuba soon increased its own production. The labor that fueled plantation production in Cuba arrived in the form of those enslaved men, women, and children who waited in the filthy barracks at the city’s edge. Estimates place the figure of slaves imported from 1790-1820 between 225,000-315,000 individuals. The population of free people of color also grew. The historian Matt Childs estimates that, by 1812, free people of color comprised 20% of the total population.

I study colonial Cuban art history during a time when the slave trade accelerated, particularly after the collapse of sugar production in Saint Domingue. Researching the history of art during this period necessarily means confronting the emergence of a slave society in Havana. I write about artists who were free men of color, and I think about how being an artist compared with other limited options of profession. Did being an artist offer a radically different means of self-identification?

Detail of slave barracks from “Plano de la Plaza de la Habana con sus fuertes adyacentes,” Author unknown, 1783

Situating these artists in their historical context means understanding a society increasingly dependent on slavery. I find this in almost every aspect of my research, including the simple act of reading early nineteenth-century Cuban newspapers. Recently, I sought out the Diario de la Habana from 1829 in search of news regarding a portraitist, and free man of color, named Vicente Escobar. I found news of Escobar and also many reminders of the slave trade and its transformation of Cuban society.

The newspaper includes bulletins on colonial administration and personnel changes, news from abroad, budgetary figures, along with mentions of books for sale, theater listings, and notices of ships leaving Havana. The notices report the ships’ destinations and announce space available for cargo or passengers. In a section titled “Parte Económica (Economic Section),” listings of items for sale appear—including the sale of homes, quitrines and volantes (horse-drawn carriages), jewelry, fabrics, and those of enslaved persons. Interestingly, the Economic Section also contains notices seeking the return of runaway slaves.

Reading the advertisements reveals the world of enslaved people in Havana. The ads contain details of African ethnic identification, literacy, language fluency, profession, dress, physical appearance, and geography. We can use the ads to track the popularity of different professions and the ethnicity of escaped slaves in relationship to the larger population of enslaved and free people.

In particular, the ads allow us to piece together the urban geography of slavery. They indicate movement in physical and legal terms. For instance, advertisements often speculate on the current location and activity of the person in question. One reads, “it is assumed [he] is in Guanabacoa in the business of rented volantes or perhaps in Matanzas, where he lived for a long time in the house of his last owner, Doña Manuela Bermúdez.” The ads link these physical locations to employment, indicating business networks amongst free people of color and the enslaved.

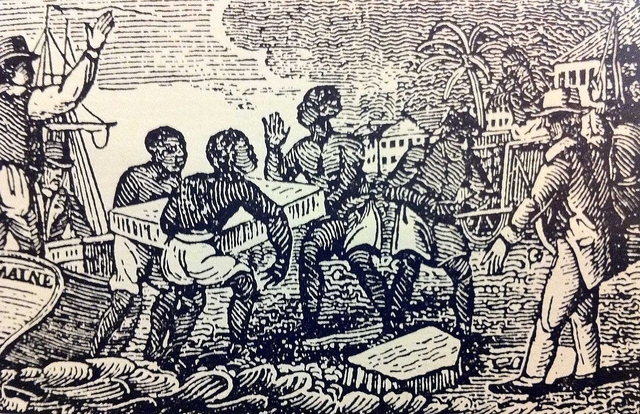

Slaves unloading ice in Havana circa 1832. Samuel Goodrich, A pictorial geography of the world (Boston, 1832)

The ads also show how enslaved people used their literacy to facilitate engagement of a legal kind. Often times, the ads simultaneously reference the carrying of fake licenses (required with the owner’s signature for an enslaved person to move freely) and the literacy of person in question. Here, the connection of literacy and forgery—of literacy and freedom—creates a sense of their agency. In reading the ads, it is hard not to find value in the humanity they reveal in the midst of an inhumane enterprise.

For example, an advertisement from March 1, 1829, states:

Three months ago a black man named Mateo escaped from Don Manel Pegudo, who acquired him from Don Manuel Sanchez, saddler, average height, thin, he is missing one or two teeth, of serious demeanor, has scars on his hands as the result of strong dyes, moves in a hurry, always dirty with a vest of coquillo [a light fabric]or a jacket of handkerchiefs, and it is likely that he carries a fake license, because he knows how to write although he hides it: the person who turns him in to the Royal Consulate, or gives correct notice of his whereabouts, will be rewarded in the house on Oficios Street, no. 29, and he who protects him will face charges.

Here the owners of the saddler-maker known as Mateo stress that he hid his ability to write. Mateo presumably did so in order to continue to fabricate fake licenses for his use and (possibly) others that he knew. Mateo’s strategic use of writing echoes another advertisement for a man who escaped from the village of Guanabacoa, located across the bay from Havana. Don Vicente Gonzalez, who listed the advertisement on February 18, 1829, does not provide a name for the man, but he does allude to his ability to write:

A light-skinned mulatto, about 40 years old, escaped from the village of Guanabacoa on the 14th of this month, unkept hair with an almost white beard, shoemaker and cook, about 5 feet tall, average weight, could carry a fake license because he knows how to write, or could sell himself as free, also false: the individual who turns him in to Muralla Street, no. 88, in this city, or in said city [of Guanabacoa] to Real Street at the house of Don Vicente González, will be rewarded with an ounce of gold, and he who shelters him will face charges.

The ad underscores that the escaped man could have carried a fake license or presented himself as a free person. At the time, a likely path to freedom existed through coartación (gradual self-purchase). The historian Alejandro de la Fuente characterizes it as an institution with a long history on the island, but he notes that obtaining a precise number of coartado slaves remains out of reach. Yet, he emphasizes how slaves could enact gradual self-purchase without their owner’s permission. As a result, “manumission was imposed on masters by entrepreneurial slaves.” The link between forgery and literacy, as presented in the ads, follows in this spirit of entrepreneurship. The ability to write provided the means to forge documents, allowing for the individual to rent (“sell”) him or herself out in a variety of trades. Tracing the mentions of literacy over time could illuminate how frequently escaped people used this strategy.

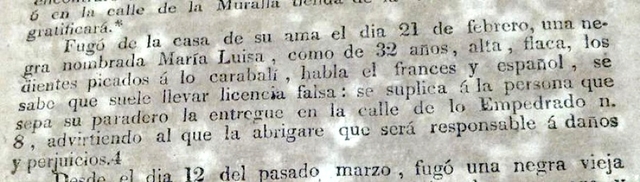

If the ads permit the tracking of physical and legal movements by escaped individuals, other details help us visualize them. An advertisement (figure 3) from April 13, 1829 reads (all translations mine):

A black woman named María Luisa escaped from the house of her owner on February 21, about 32 years old, tall, thin, with filed teeth in the Carabalí fashion, she speaks French and Spanish, it is known that she usually carries a fake license: we ask that the person who knows her whereabouts bring her to Empredrado Street, no. 8, with the warning that the person who protects her will face charges.

The mention of María Luisa’s filed teeth speaks to her ethnic self-identification as a Carabalí woman, from the Cross River region in Nigeria. The anthropologist Fernando Ortiz describes this style of filed, pointed teeth as characteristic of Carabalí men and women. He links the style, in his Los negros curros, to the fashion of the free black urban “underworld” in colonial Havana. María Luisa’s fluency in French could signify that her owners were French émigrés, perhaps part of the groups that came to Cuba after the outbreak of revolts in Saint Domingue. If her owners rented María Luisa to others, they would have noted her language skills.

Unquestionably, the advertisements evoke the image of the person they describe. Details of physical appearance abound, like the “four marks from a vaccination” on the arms of an escaped boy, of the Gangá ethnic group, 12 years old. He responds to “Manuel” and knows how to say his master’s name, the advertisement states. Another describes the dress of 14 year-old Margarita, of Congo ethnicity, who escaped in January 1829. She wore a “striped tunic with a blue background and white squares, large handkerchief, and white shawl.” Distinct images—however subjective in our contemporary imagining—emerge from these advertisements.

The ads help us see individuals. Although the dark horror of slavery remains, the ads show for whom—and how—escape was possible. They present us with a sense of their movements and motivations, like Francisco Puche. He escaped in April 1829 and was said to be somewhere near the docks of Guanabacoa, forged license in hand.

Further Reading:

The advertisements crop up in the scholarly literature on slavery, abolition, and free people of color in colonial Cuba, but I have not come across a compilation that considers them as a whole or assembles them into a documentary history, like Lathan Algerna’s Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History from the 1730s to 1790 for colonial Virginia. A website on the “Geography of Slavery” expands the scope of Algerna’s project and includes a searchable database. A similar project for the Cuban advertisements would be invaluable.

Childs, Matt D. The 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle against Atlantic Slavery. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Deschamps Chapeaux, Pedro. El negro en la economia habanera del siglo XIX. La Habana: Union de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba, 1971.

de la Fuente, Alejandro. “Slaves and the Creation of Legal Rights in Cuba: Coartación and Papel.” Hispanic American Historical Review 87, no. 4 (2007): 659-692.

García, Guadalupe. “Beyond the walled city: urban expansion in and around Havana, 1828-1909.” PhD diss., The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2006.

Knight, Franklin. Slave Society in Cuba during the Nineteenth Century. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1970.

Ortiz, Fernando. Los negros curros. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1986.