“Why Does S Look Like F?”: A Guide to Reading Very Old Books

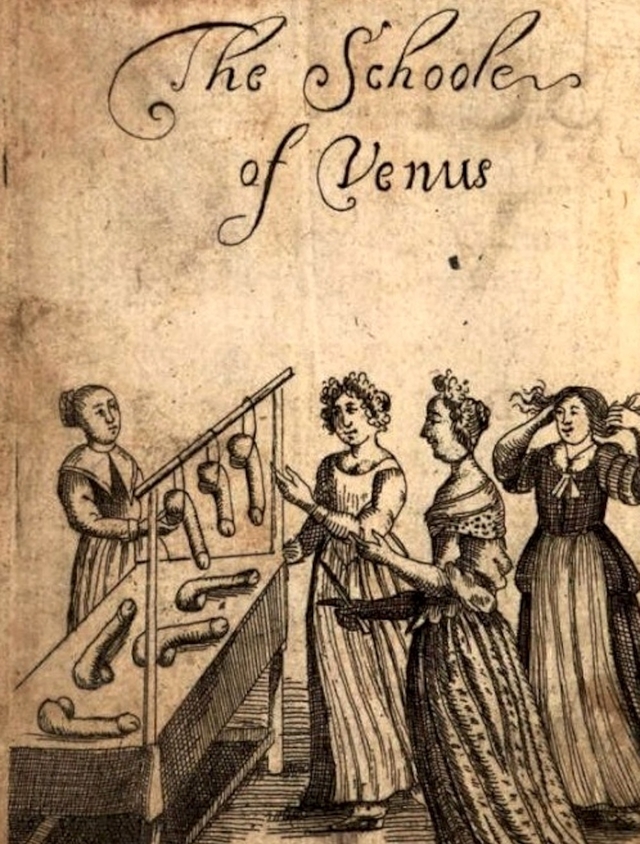

Last month, I came across a recently digitized book from 1680 with the innocuous-sounding title The School of Venus. After browsing it for a few moments, however, I realized I’d stumbled onto something truly interesting. It was a sex manual, and a rather free-spirited one at that, as the frontispiece engraving suggests:

It occurred to me that this was the sort of thing that would appeal to people outside of my specialist field of early modern history, and I began writing a blog post about it for the The Appendix. Reading over my draft, my co-editor Chris brought up something that I’d taken for granted: like any 17th century book, the text employed what’s called the ‘long’ or ‘descending’ S.

“If this has the reach I think it might,” he said, “you need to explain that.” I initially thought the suggestion was slightly condescending to my readers: doesn’t everyone know about the old-timey S? Its right there in the first line of the Bill of Rights, after all.

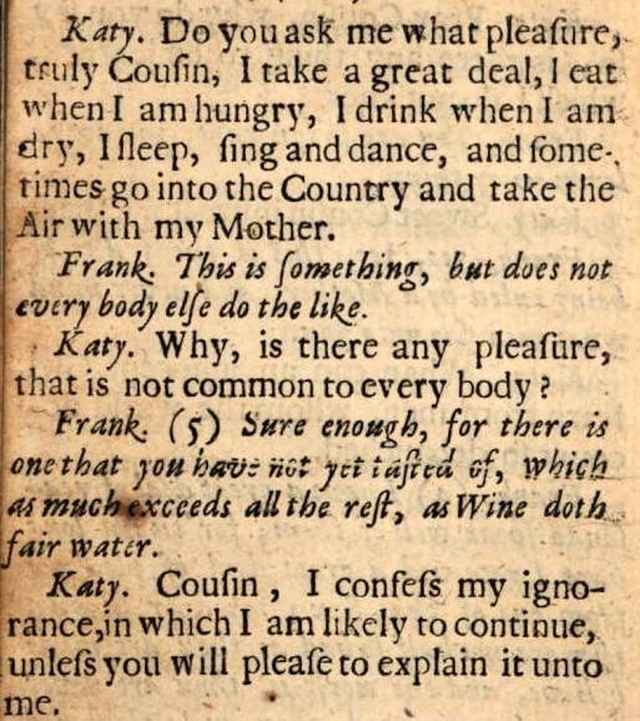

A sample page from The School of Venus (London, 1680), showing the characteristic long S (ſ) of early modern English.

Then I snapped out of it and realized that I was falling into the myopia typical of anyone who spends a long time in a specialist field. Like a biologist assuming that laypeople would know what hemoglobin is, I was forgetting that not everyone spends their days reading early modern texts. I put in a very short explanation of the S/F distinction, but even so, when the post got picked up by Slate and Jezebel, a significant proportion of the comments were about how hard it was to read the old-fashioned writing.

So I write today to give an accessible overview of how to read books and manuscripts from the early modern era - what scholars call the period spanning the early Renaissance to the French, American and Industrial Revolutions. To tackle the S first: the long S dates back to the old Roman cursive handwriting, and survived as an artifact in the earliest printed book fonts, which were modeled on various medieval handwriting forms. The key thing to understand about the long S is that it occurs only in the middle of words, never at the beginning or end. Thus the title of School of Venus would not feature a long S in either its first or final letters, but words like ‘Castle‘ or ‘Lost’ would appear as ‘Caſtle’ and ‘Loſt.’

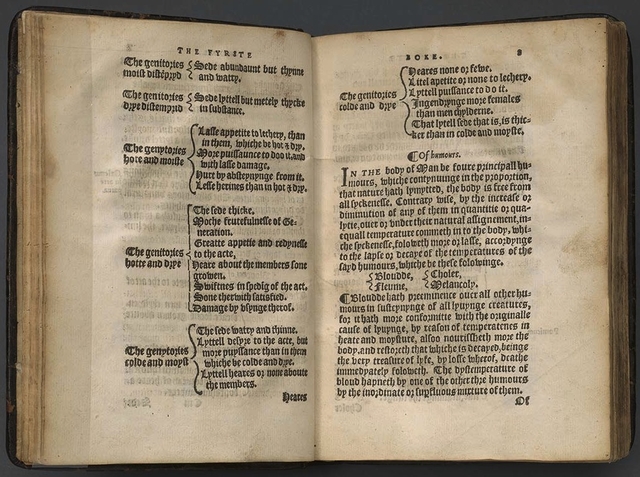

So far so good. Things get trickier, however, when we try to read the earliest books printed in English, which typically featured variants of the German blackletter font. Here’s a two page spread from one of the earliest English medical texts, Thomas Elyot’s The Castell of Helth (1536):

Thomas Elyot’s The Castell of Helth, published in 1536, displaying its characteristic blackletter font.

A variant of the long S is in full effect here, but so are a number of other features that look unusual to modern readers: capital letters like ‘T’ or ‘H’ take elaborate forms, and lowercase ‘d’ and ‘r’ retain the look of Carolingian miniscule or Gothic blacklister, the handwritings of choice of medieval monks.

The top of the second page is intended to help with diagnosing sexual trouble, and the symptoms following the heading “The genitories [i.e. genitals] colde and drye” read:

-Heares [i.e. hairs] none or fewe

-Littel apetite or none to lechery.

-Littel puiſſance to do it.

And so forth. I remember being a bit taken aback the first few times I tried to read books in this font, but it ends up registering in the brain as just that: a different font, but the same alphabet. Reading early modern manuscripts (the practice of which is called ‘paleography’) can be a different matter, however. To start us off easy, here’s a lovely script from the late 17th century written by a clerk or secretary at the Royal Society of London:

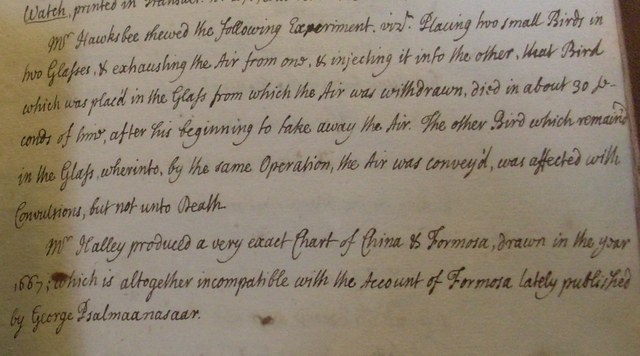

The minutes of a 1704 record book from the Royal Society, detailing an early experiment with a vacuum: “Mr Hawksbee shewed the following Experiment, viz: Placing two small Birds in two Glasses, & exhausting the Air from one, & injecting it into the other, that Bird which was plac’d in the Glass from which the Air was withdrawn, died in about 30 seconds of time, after his beginning to take away the Air. The other Bird which remain’d in the Glass, whereinto, by the same Operation, the Air was convey’d, was affected with Convulsions, but not unto Death.” The Royal Society of London, photograph by the author

The script and language here is not all that different from modern English. The key differences are in the punctuation (early modern English, like modern German, tended to capitalize proper nouns), and also in certain contractions which are unused today, like “convey’d.” As a side note, I kept this snippet on hand because it contains a rare reference to an impostor named George Psalmanazar, who I just published an article about.

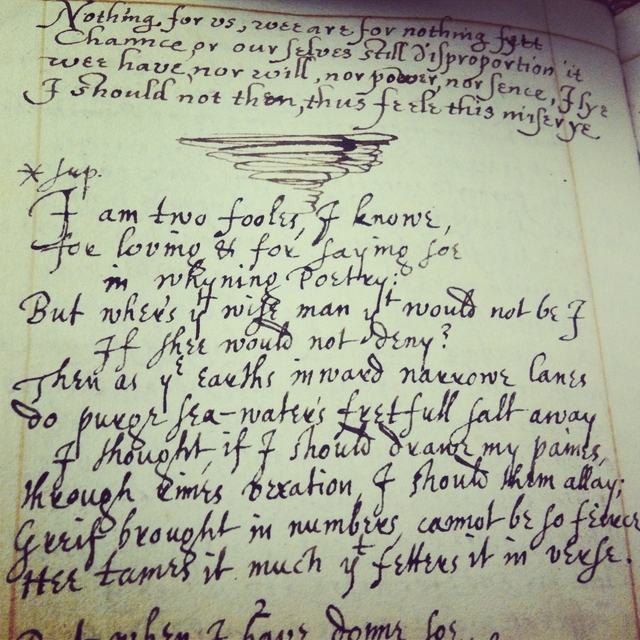

Moving backwards in time to milieu of the great poet John Donne in the 1610s and ’20s, we find things a little more unfamiliar. (Note that the original version of this post assumed that this text was actually written by Donne; two Donne specialists have informed me that this is quite unlikely, and that it is most likely a copy by a different hand).

An early copy of his poem “The Triple Fool”: “I am two fooles, I knowe / For loving & for saying soe / in whyning Poetry;/ But where’s yt wise man yt would not be I / If shee would not deny?” The Huntington Library, photograph by the author

The ‘E’s here are typical of Donne’s era in that they resembled reversed ‘3’s, and his uppercase ‘I’ looks like an F or J. The most difficult difference in this script - or at least the one that tripped me the most when I was learning it - is the variation in the ‘S’ shapes. In the second line, the copyist writes “saying soe” using a form with a looping tail, but in “fools,” he uses something like a modern cursive lowercase s. Finally, we find in the last line a very common 17th century abbreviation: ‘yt’ for ‘that.’ What appears to be a ‘y’ here is actually the descendant of the obsolete Old English letter thorn (Þ), which also appears in the classic construction “Ye Olde Shoppe.” (The ‘Ye’ would actually have been pronounced like ‘the’). You can see the writer is using ‘Ye’ there in the middle: “Then as the Earths inward narrowe lanes…” As an interesting note, this draft of the poem differs from the final version - in the print edition, Donne substituted ‘crooked’ for ‘narrowe.’

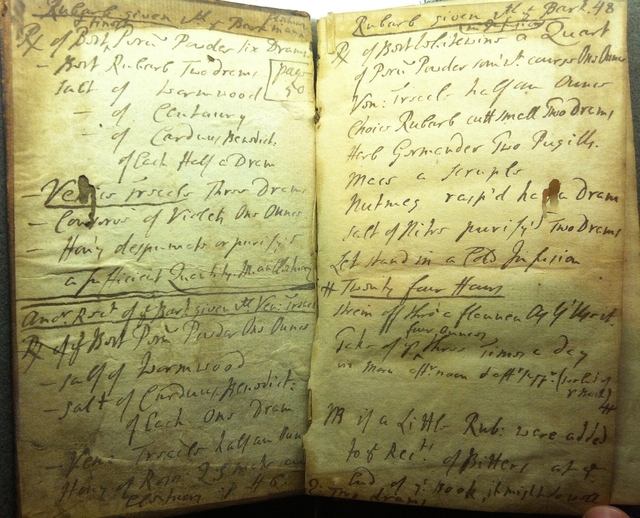

Now lets move on to some truly difficult paleography. This is a photograph I took of a book at the John Carter Brown Library called The Sea Surgeon, or the Guinea-Mans Vade Mecum (1729). The inside flaps of this copy of the book feature some fascinating notes by an actual practicing marine surgeon who was trying out various cures for scurvy, plague and fevers found in the book. He used a handwriting that was marked by his profession, featuring a number of abbreviations that it took me some time to puzzle out. I’d say this is fairly advanced-level paleography - although I should add that compared to my colleagues who work on things like sixteenth-century French bankruptcy cases or Scottish witchcraft trials, reading this is absolute child’s play.

The inside pages of John Aubrey’s The Sea Surgeon (1729). The John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, photograph by the author

At upper left, we find the heading “Rubarb given wt. ye Bark,” which is to say “Rhubarb given with the [Peruvian] Bark.” (Known primarily to modern eaters for its famed pie-partnership with strawberries, rhubarb was actually a highly prized and expensive medicine in this period.) Below the heading we find a list of ingredients supplied to a sick sailor, beginning with the still-familiar “Rx” prescription symbol: “[Prescription] of Bark Peru[viana] Powder lix [59] drams.” The surgeon then lists “Salt of Wormwood, Salt of Centaury Salt of Carduus Benedict[us], of Each Half a Dram.”

Of the ingredients of this witches brew, the most familiar to modern readers is probably wormwood, the possibly intoxicating herb which makes absinthe so infamous. There’s a good amount of shorthand being used here, of the sort that a doctor or apothecary would use in jotting notes to others in the field. But in fact this is a fairly easy to read example of how early modern apothecaries wrote - I’ve seen much, much worse, and there are countless pages of documents which even after five years of training, I’m still unable to read. With practice and patience, though, virtually anything is readable.

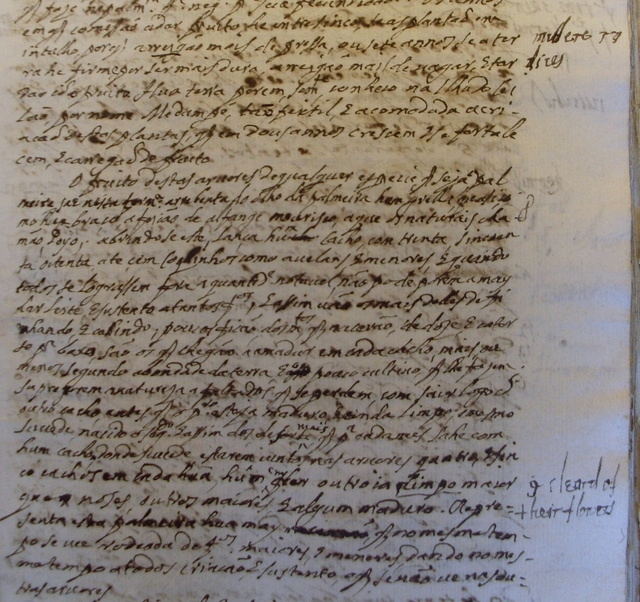

A late-seventeenth-century Portuguese report on coconut trees adapted from the writings of Jéronimo Lobo. The Royal Society of London, photograph by the author

Finally, here’s a page from a document that is currently beyond my own paleographic abilities. Its been waiting in a computer folder for around a year now, and it has resisted my attempts at a word-for-word transcription due to its abbreviations and unclear lettering. It was written by (or at least dictated by) a rather fascinating Portuguese Jesuit named Jéronimo Lobo, who lived for many years in Ethiopia. Lobo was an extremely inquisitive man who lived into his eighties, so he became an important informant about tropical nature for the scientists of the Royal Society. In this document, he explains the nature of the coconut tree. I can translate a few lines (like O fruto das arvores de qualquer especie, “The fruit of any kind of this tree”), and scattered phrases like mais or menos segundo abundade de terra, nascido, cultivo make it clear that he’s writing about how to grow and cultivate coconuts. But a complete transcription eludes me - a fact that may have been anticipated by the reader whose marginal glosses are visible at right, marking out muttere radices (“to change the roots” or “transplant” in Latin and cleard of their flowers in English).

At any rate, I hope this brief and idiosyncratic overview to reading early modern texts has been helpful, and above all, I hope it spurs some further interest in the fascinating works out there, waiting for readers. Not everything from the 17th and 18th centuries is as immediately engaging as The School of Venus, but there are a lot of untapped riches waiting for readers.