Meiji Meth: the Deep History of Illicit Drugs

“We’re not going to need pseudoephedrine,” Walter White mutters through clenched teeth. “We’re going to make phenylacetone in a tube furnace, then we’re going to use reductive amination to yield methamphetamine.” Chemicals go in, and out come 99.1% pure crystals glittering with the brilliant azure of a New Mexico swimming pool.

The invention of Breaking Bad’s blue meth has become the stuff of television legend, and has even inspired a spate of real world knock-offs. But few know the true origin stories of illicit drugs—for instance, the strange fact that methamphetamine was actually invented in 1890s Japan.

Chemists have been fascinated by recreational drugs for a very long time. Robert Hooke, the short-tempered genius who discovered cells, was also the author of the first academic paper on cannabis. In the fall of 1689, Hooke ducked into a London coffee shop to purchase the drug from an East Indies merchant, and proceeded to test it on an unnamed “Patient.” It was evidently a large dose. “The Patient understands not, nor remembereth any Thing that he seeth, heareth, or doth,” Hooke reported. “Yet he is very merry, and laughs, and sings… and sheweth many odd Tricks.” Hooke observed that the drug eased stomach pains, provoked hunger, and could potentially “prove useful in the Treatment of Lunaticks.”

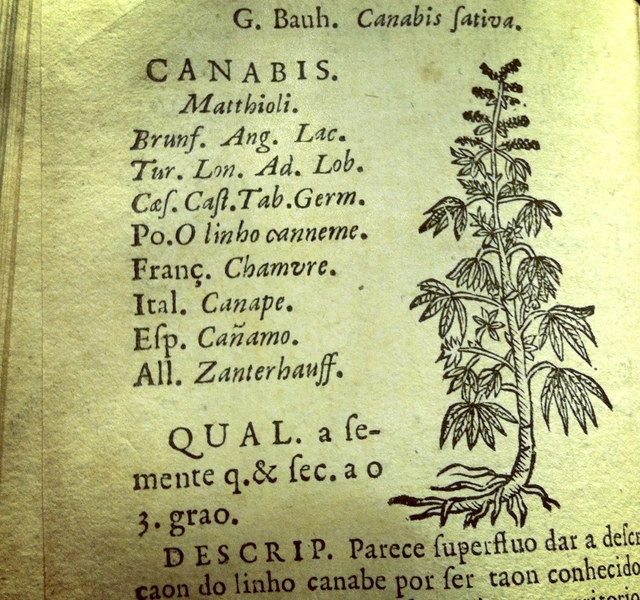

An early depiction of cannabis from Jean Vigier’s Historia das Plantas (1718), originally published in French in 1670. The John Carter Brown Library at Brown University

Hooke also strongly hinted that he’d personally sampled his coffee shop score: the drug “is so well known and experimented by Thousands,” he wrote, that “there is no Cause of Fear, tho’ possibly there may be of Laughter.” (There were good reasons that Hooke’s readers might be afraid of a new drug—this was, after all, a world where pharmacies sold ground up skulls and Egyptian mummies as medicine).

Historians have largely ignored Hooke’s adventures with cannabis, entertaining as they may be. Albert Hoffmann’s accidental discovery of acid, however, is well known. In fact it’s arguably the most famous tale of drug discovery, challenged only by August Kekulé’s famous dream-vision of the benzene molecule as an ouroboros, which preoccupied Thomas Pynchon in Gravity’s Rainbow.

Even LSD, however, has a more obscure prehistory. Roman physicians described a painful disease called the sacred fire (sacer ignis) which by the Middle Ages came to be known as St. Anthony’s Fire—“an ulcerous Eruption, reddish, or mix’d of pale and red,” as one 1714 text put it. Sufferers of this gruesome illness, which could also cause hallucinations, were actually being poisoned by ergot, a fungus that grows on wheat. Several authors, most recently Oliver Sacks in his excellent book Hallucinations, have noted a potential link between ergot poisoning and cases of dancing mania and other forms of mass hysteria in premodern Europe.

“The Beggars” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, a painting believed to show victims of ergotism. Wikimedia Commons

By the 1920s, pharmaceutical firms began investigating the compounds in ergot, which showed potential as migraine treatments. A Swiss chemist at the Sandoz Corporation named Albert Hoffman grew especially intrigued, and in November 1938 (the week after Kristallnacht) he synthesized an ergot derivative that would later be dubbed lysergic acid diethalyamide: LSD for short.

It was not until five years later, however, that Hoffman experienced the drug. Immersed in his work, Hoffman accidentally allowed a tiny droplet of LSD to dissolve onto his skin. He thought nothing of it: hardly any drugs are psychoactive in such minute doses. Later that day, however, Hoffmann went home sick, lay on his couch, and

sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away.

Three days later, the chemist decided to self-administer what he assumed was a tiny dose to further test the drug’s effects. He took 250 micrograms, which was actually roughly ten times higher than the threshold dose. Within an hour, Hoffman asked his lab assistant to escort him home by bicycle. Cycling through the Swiss countryside, Hoffman was shocked to observe that “everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror.”

By the time he arrived home, Hoffman decided to call a doctor. However, the physician reported no abnormal physical symptoms besides dilated pupils, and Hoffmann began to enjoy himself:

Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves in constant flux.

Hoffman awoke the next morning “refreshed, with a clear head,” and with “a sensation of well-being and renewed life.” In an echo of Hooke’s report about his friend’s cannabis experience, which left him “Refreshed…and exceeding hungry,” Hoffman recalled that “Breakfast tasted delicious and gave me extraordinary pleasure.”

One of the interesting aspects of Hoffman’s story is how detached it was, both temporally and culturally, from the 1960s context with which LSD is often associated today. This delay between the scientific identification and the popular adoption of a drug is a common story—and in no case is it more stark than in the gap between the discovery of meth and its widespread adoption as an illicit street drug. Methamphetamine was synthesized by a middle-aged, respectable Japanese chemist named Nagai Nagayoshi in 1893.

An elder statesman of Japanese science and medicine, Nagayoshi Nagai and his wife hosted Albert Einstein in 1923. Wikimedia Commons

A member of the Meiji Japanese elite, Nagayoshi devoted much of his energy to the chemical analysis of traditional Japanese and Chinese medicines using the tools of Western science. In 1885, Nagai isolated the stimulant ephedrine from Ephedra sinica, a plant long used in Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine.

The year before, in July 1884, Sigmund Freud had published his widely-read encomium to the wonders of cocaine, Über Coca. Cocaine was radically more potent than coca leaves, and chemists the world over were on the lookout for other potential wonder drugs. It’s likely that Nagai hoped to work the same magic with ephedra—and in many ways he did. Ephedrine is a mild stimulant, notable nowadays as an ingredient in shady weight-loss supplements and as one of the few drugs historically permitted to Mormons, (although see this response post for an interesting breakdown of the debate over “Mormon tea”).

But in 1893, Nagai blazed a chemical trail that would live in infamy: he used ephedrine to synthesize meth.

As with LSD, it took the world a couple decades to catch on. In 1919, a younger protégé of Nagai named Akira Ogata discovered a new method of synthesizing the crystalline form of the new stimulant, giving the world crystal meth.

It wasn’t until World War II, however, that meth became widespread as a handy tool for keeping tank and bomber crews awake. By 1942, Adolf Hitler was receiving regular IV injections of meth from his physician, Theodor Morell. Two years later the American pharmaceutical company Abbott Laboratories won FDA approval for meth as a prescription treatment for a host of ills ranging from alcoholism to weight gain.

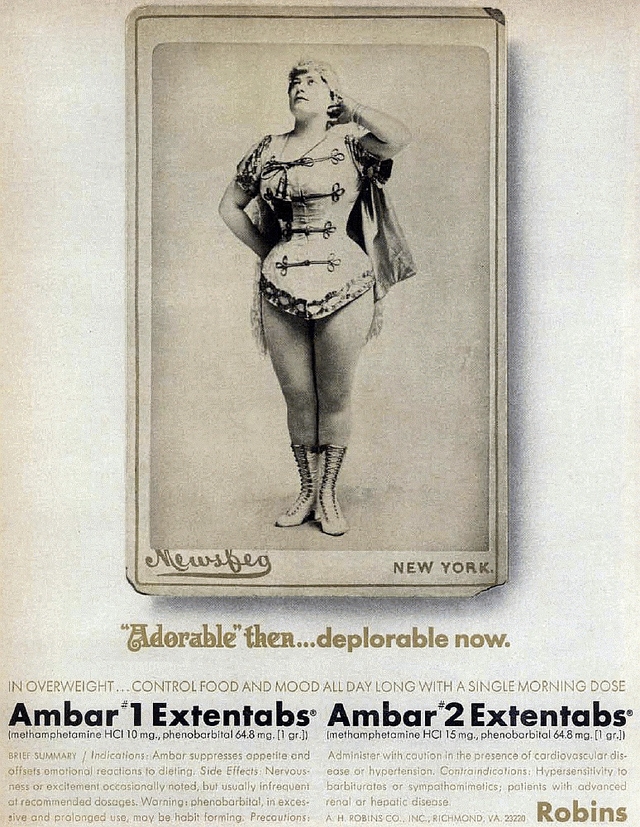

Ambar: a potent mixture of methamphetamine and phenorbarbital, shown here in a mean-spirited 1964 advertisement that appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association (Vol. 1, No. 5385).

The rest is history—by the 1960s, “tweakers” had made meth a byword for deranged drug addicts, and it lost its standing in the scientific and medical communities. Much like heroin, which was originally marketed by Bayer as a companion to aspirin (the company still technically owns the copyright to the name), meth began life as a wonder drug only to segue into a depraved middle age.

It all points to an interesting and unexplored dichotomy in the history of drugs: there’s a huge gap between the inventors of illicit drugs—usually rather austere, cerebral and disciplined—and their consumers.

I’m guessing that Robert Hooke, Nagayoshi Nagai, Albert Hoffman, and Walter White would have a lot to talk about.