Issue Four Preview: Jackson Unchained

We’re currently in the midst of preparing Issue Four of The Appendix, which will be entitled "Off the Map" and will launch on October 2. Here’s a sneak peek of an article we’re excited about: “Jackson Unchained: Reclaiming a Fugitive Landscape” by Susanna Ashton and Jonathan Hepworth. Look for the complete article this fall.

“I may as well relate here, how I became acquainted with the fact of there being a Free State. The “Yankees,” or Northerners, when they visited our plantation, used to tell the negroes that there was a country called England, where there were no slaves, and that the city of Boston was free; and we used to wish we knew which way to travel to find those places. When we were picking cotton, we used to see the wild geese flying over our heads to some distant land, and we often used to say to each other, “O that we had wings like those geese, then we would fly over the heads of our masters to the ‘Land of the Free.’”

- John Andrew Jackson, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina (London, 1862).

Although many accounts of runaway slaves from the Antebellum South survive, the story of John Andrew Jackson’s escape is something special. Finding an advertisement calling for the capture of a specific person is rare in slave history, but we have found a detailed one seeking Jackson. We can use that advertisement alongside his own account of his escape, and our own geographical understanding of the region, to triangulate his multiple routes to freedom. Not only can his specific and vague references to landmarks help us re-imagine his route over rivers and roads, thus validating his claims, but we can also discover how freedom-seekers like Jackson manipulated their enslavers’ notions of flight.

In other words, Jackson didn’t run the way his former masters thought he would run. Nor, later in life, did he run in the way we might imagine him running. His path provides us with a unique glimpse into how one slave lived out his lifelong imaginary navigation of his surroundings and inner life. It reveals a multi-layered meaning of landscape that Jackson believed he could reclaim before he died, and that we might still reclaim for him today.

The particulars of Jackson’s storied life are as follows: he was born in Sumter District, South Carolina in about 1825 and was owned by Robert English, a successful landowner with various properties and a host of relatives to share and trade slaves with. The plantation Jackson lived on was in a town once known as English Crossroads, later as Magnolia, and finally as Lynchburg. Despite a brutal life of labor and abuse, he found some brief happiness with Louisa, a young woman he married who lived on a nearby plantation owned by the Law family. His owners objected to his marriage and to his spending time with his wife and Jenny, the daughter Jackson and Louisa conceived. Despite repeated whippings for leaving his plantation to be with Louisa, Jackson remained devoted to his family and determined to keep crossing the land between the English and Law plantations.

In 1846, however, Jenny and Louisa were sold or sent to Houston Country, Georgia. Jackson’s devastation knew no bounds, and he resolved to use the rapidly-degrading sanity of Robert English to his advantage. With his owner collapsing into dementia, oversight and discipline of the plantation were lax. Jackson began to hatch a plan for escape. If he couldn’t join Jenny and Louisa, he would escape slavery entirely and perhaps someday, somehow be reunited.

Jackson managed to trade some chickens for a pony that a neighboring slave had somehow obtained. He hid the pony deep in the woods. On Christmas day, he took advantage of the customary three-day holiday and fled on horseback for Charleston. He had often been to Charleston to drive his master’s cattle to market and knew the route well. Unlike many fugitives forced to brave unknown terrain, Jackson’s flight to Charleston was through familiar turf.

It was still dangerous, however, and while he had not worked out the details of what precisely he would do in Charleston, simply and plausibly traveling the over 100 miles of main roads to the city was going to be his greatest challenge. Jackson’s flight over that landscape was thus both typical and atypical of the larger fugitive slave experience.

Fugitives from slavery each had their own horrible story to tell and their own circumstances that led them to seek freedom though “self-theft,” to use the parlance of runaway advertisements in newspapers of the time. But there are some general patterns within the flights of men and women enslaved in the inland South.

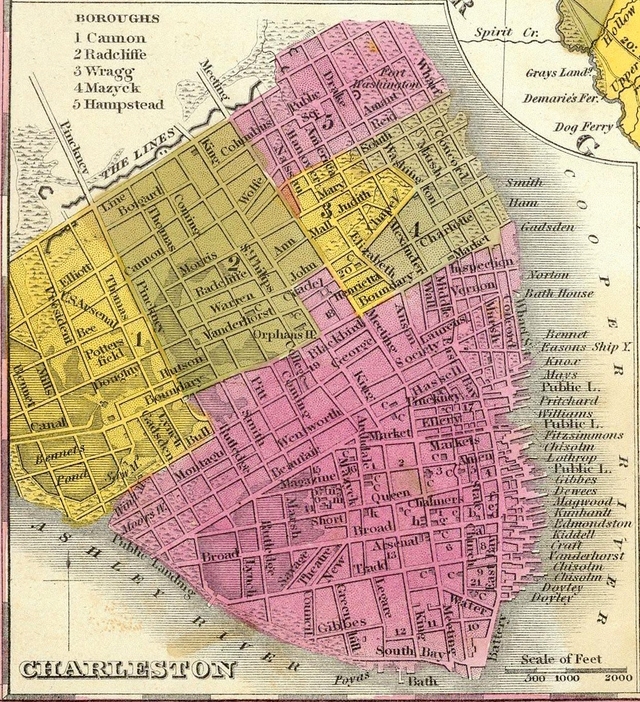

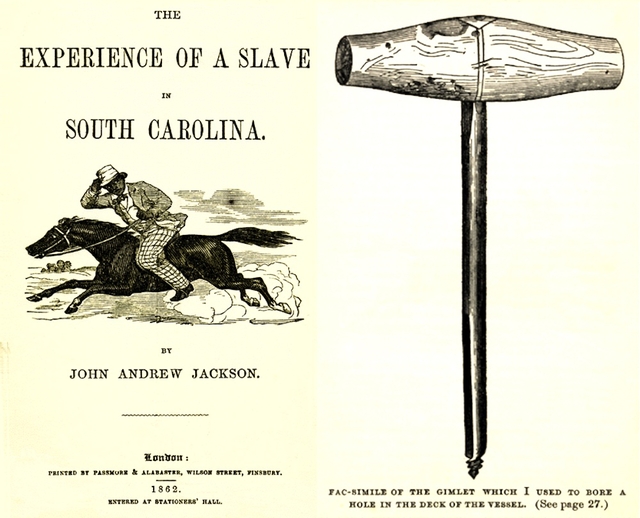

The title page and an illustration from Jackson’s memoir, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina (London, 1862). Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina

To begin with, a vast majority of runaways likely left without any specific plans to abscond north. Rather, they were often fleeing immediate punishment or danger with the intent of returning once the circumstances or threat had changed. A northern escape was a colossal undertaking for people enslaved in the Deep South who had little access to trains or boats. The geographic challenges alone were huge.

Another common motivation for short-term flight, sometimes termed petit marronage, was what took Jackson to visit Louisa; individuals would leave their plantations to see parents or spouses for limited periods of time. This resistance-through-flight was dangerous, of course, for punishments upon return could be murderous. Whether calculated or impulsive, those kinds of flight were still powerful acts of defiance that indicated to overseers or masters that some treatment would not be endured. Despite threats of violence and cruelty, men and women still held some negotiating power: labor was a temporal force, and it meant more at planting or harvest time. If a person could hide for even a week or two, they could deprive their master of labor at an exceptionally critical moment. Punishing that slave too harshly upon their return could be only a pyrrhic victory.

Jackson’s flight this time, though, was the less common form of escape: grand marronage. He was heading south to Charleston, with plans to then head north for permanent freedom. He had no knowing assistance from anyone, black or white, and he travelled on the roads in plain sight on a pony.