Music and Color: the French Connection

While researching The Appendix’s current issue, which is devoted to music and sound, we grew interested by a related topic: that of synesthesia. How do sound and color fit together, and why do some minds draw intensely vivid connections between the two? Lawrence E. Marks’s The Unity of the Senses, for instance, described Newton’s belief in “a real analogy between elementary colors and the notes of the musical scale.” Newton’s prism experiments famously established the ROYGBIV rainbow of colors which combine into white light—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. But for Newton (as for other Enlightenment thinkers like Louis-Bertrand Castel, described in more detail below) the seven colors also corresponded to the seven notes of the musical scale.

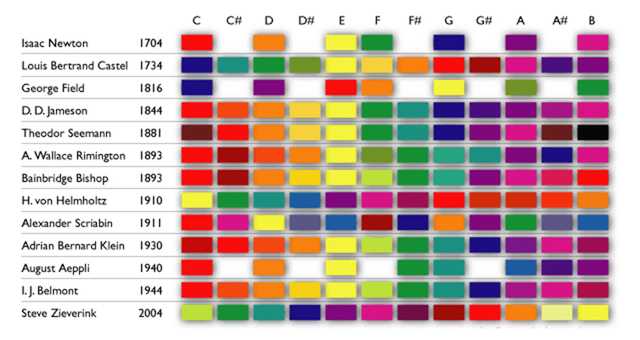

We poked around the Internet looking for more information, and found useful resources like this chart by Fred Collopy, which visualizes three centuries of claims about the relationship between music and color:

Yet so much of what is available about sound and color online restricts itself to pointing out the inherent coolness of synesthesia and leaves it at that. Luckily, Gina Rivera, who recently received her PhD in historical musicology from Harvard, offered to fill in the blanks.

—The Editors

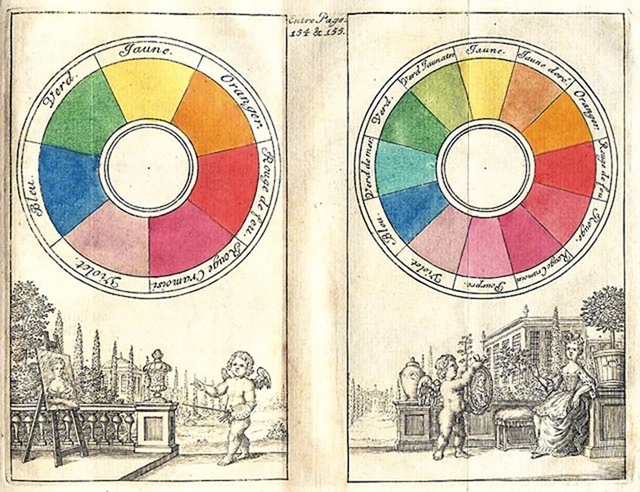

Eighteenth-century French ideas about music and tone color crystallized in two related phenomena: the early modern interest in musical instruments with an optical dimension, and the codification of a critical language for tonality in the early nineteenth century, particularly among the mathematician and musicologist Alexandre-Étienne Choron and the polymath François-Joseph Fétis. This attraction to musical color interacted with broader cultural impulses, from the dialogue of sound and science to a vogue for discussing musical repertories in tandem with the visual arts.

Between 1725 and 1825, fascination with musical color shifted from practice to theory, from scientific experimentation and the construction of new musical instruments to a more theoretical discussion of color and tone. This blog post is about a polarizing figure who sought to build musical color-instruments: Louis-Bertrand Castel. In a subsequent post, I turn to Choron, Fétis, and others who traced how musical harmony and its colorful chromaticisms had changed since the eighteenth century, and what those changes meant for instruments, players, and the public who discussed their scintillating sounds and performances.

Fascination with the interplay between color and music dates to Hellenic times, when musical consonance was studied in relation to the harmony (or disharmony) of color combinations. Aristotle regarded color as an element existing in the boundaries of things. He described several hues compounded according to mathematical proportions—exactly like musical harmonies—as the most pleasant to behold, especially crimson and purple.

The primary colors were most singled out for the ways that they gestured toward musical intervals—an analogy which opened up space for Newtonian theory. In the sixteenth century, the composer and theorist Gioseffo Zarlino associated the musical intervals of the unison and octave with the colors white and black, further speaking to the affinities of red, green, and blue. In An Hypothesis explaining the Properties of Light, discoursed of in my several Papers (1675), Newton himself associated the colors of the spectrum with tonal intervals, describing the strength of the vibrations produced by reds and yellows, the weakness of blues and violets, and the corresponding workings of the perception of diverse tones. As the harmony or dissonance of sounds proceeds from the proportions of vibrations in the air, the harmony of some colors like gold and blue proceeds from the proportions of ethereal vibrations.

Interestingly, almost a full century before Newton would develop his theories, the Venetian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo was at work systematizing elaborate correspondences between music and color. The Mantuan historian and Tasso devotee Gregorio Comanini singled out this musical color system for its unique reliance on shading rather than hue.

This genealogy of fascination with color and music held pride of place in Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment France, where the composer Jean-Philippe Rameau was an avid reader of Zarlino and where the vogue for such naturalistic colorists as the painter Antoine Watteau extended well into the eighteenth century. As the musicologist Georgia Cowart has pointed out, the popularity of Watteau maintained ties to the subjects of many of his portraits, including figures from the world of contemporary ballet and commedia dell’arte.

Antoine Watteau, Pierrot, autrefois dit Gilles (1721). Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des peintures, M.I. 1121

Antoine Watteau, Comédiens italiens (1721). Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1946.7.9

Thomas Crow has even remarked on connections between these paintings and the custom of donning costumes in the manner of the Comédie-Italienne as an expression of resistance to monarchical authority. The affinity between musical practices and color theory nevertheless extended much deeper than this.

As news of an “ocular harpsichord, with the capacity to paint sounds” spread through Paris and the provinces in the early decades of the eighteenth century, its mastermind Louis-Bertrand Castel, the Jesuit mathematician who would also publish the Optique des couleurs (1740) and a critical assessment of Newtonian optics, admitted that his project owed much to the musical thought of the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher.

Castel’s reading of Kircher’s Musurgia Universalis (1650) inspired him to imbue a musical instrument with visual properties. The idea was that listeners confronting its sounding material would “be astonished to see it sown with the most vivid colors.”

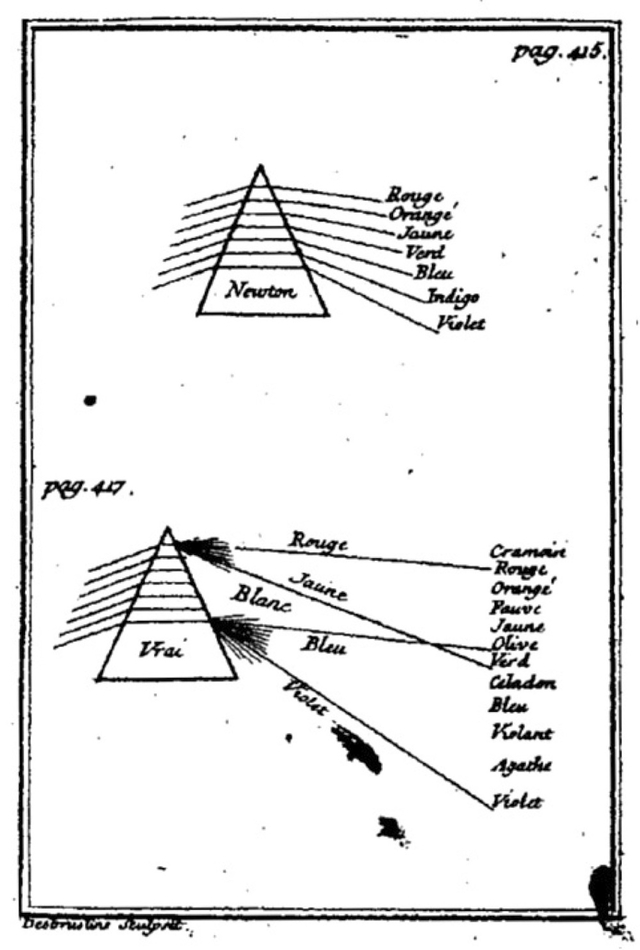

A graphic showing the comparative consideration of Newtonian spectral color and darkness and light, from the Optique des couleurs (1740) by Castel.

The engineering of the instrument proved more unwieldy than its conceptualization, leading a number of his colleagues to dismiss Castel as a misguided musical Newtonian. Voltaire accused him of sophistry in a letter to Rameau, claiming that Castel was not the great mathematician he purported to be.

In reality, Castel himself professed little desire to turn the elaborate intellectual fantasy of a color keyboard into a working reality. Yet in spite of the cynicism of Voltaire and the Parisian public, Castel finally produced what he considered to be a functioning ocular instrument, exhibiting a symphony of levers, shutters, colored paper, and candles in a keyboard twice the size of a modern grand piano.

The instrument was unveiled in London the very year that Castel would die. The widespread demand for the novel instrument marked Castel as a progressive intellectual figure and an architect of something the Parisian public felt it desperately needed. A journal in the middle of the eighteenth century lauded his project as one that would bolster the “current renewal of the august Scepter of our Monarchs.” Infusing the musical experience with color was seen as more than a novelty or passing fancy: it was a mark of French national pride.

Yet there is nothing distinctly French about this history of fascination with the interplay between music and color. As we continue to dwell on color in descriptions of musical expression, orchestration, and our own experiences of listening, we too maintain ties to the early synesthetic fantasies of Castel.