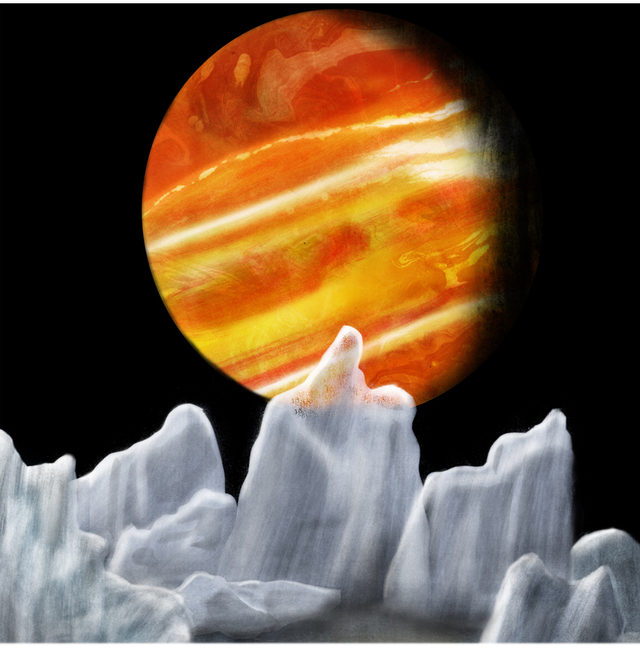

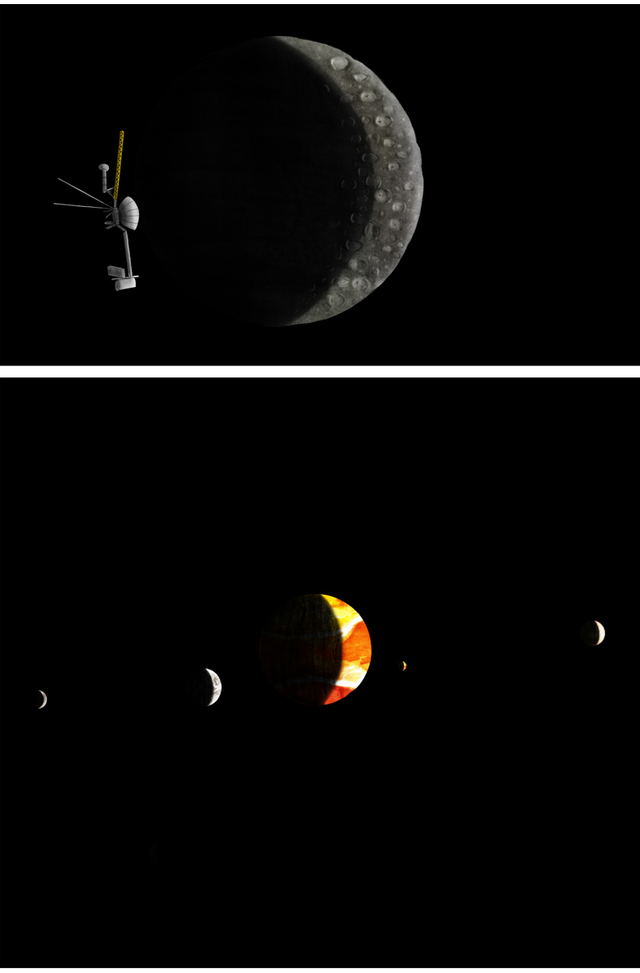

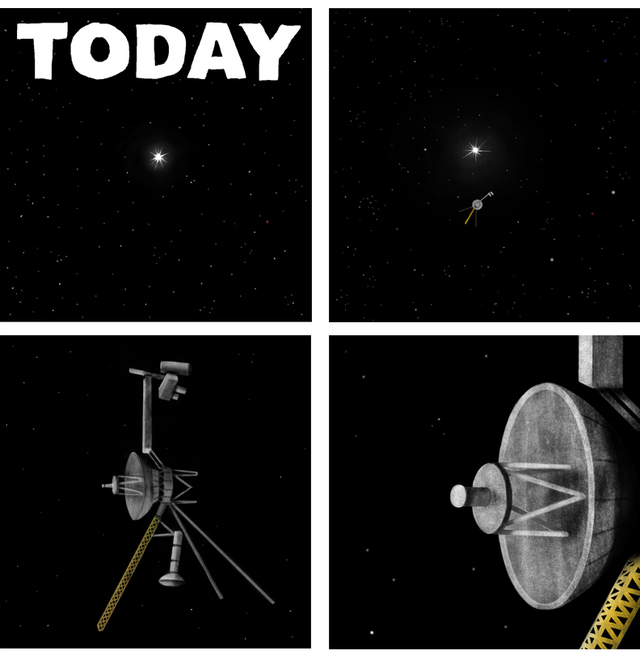

Scenes from Jed McGowan’s Voyager series.

Scenes from Jed McGowan’s Voyager series.

Does Outer Space Have a History?

A few weeks ago on The Toast, Mallory Ortberg wrote a piece called “Another Lifeless, Empty Planet Found.” Beginning as a faux news report about scientists announcing their discovery of earth-like planets, it ends up sounding like Werner Herzog writing for The Onion:

“In some ways,” Travers said, trying to light a cigarette with stained and trembling fingers, “it’s more of a punch in the gut than ever, finding a sun so much like our own, and a planet that exists well within the conditions to produce life but doesn’t. Like it’s a blind and gleeful mockery of our own existence. Like looking at your own empty grave and seeing your name erased from the headstone.”

She lit a new cigarette from the dying embers of the old one.

“There might be ice, though,” she added hopefully.

Aside from being a clever satire of the “it’s a wonderful universe” school of science writing, it also raises a good question about what we expect from nature. Does everything we learn about the universe have to make us feel good about ourselves?

In many ways, the history of science is the history of humans getting progressively more freaked out by their own cosmic insignificance. Most cultures’ origin stories tend to be about a plucky band of survivors overcoming the odds and becoming the chosen people — or, at least, the people who really matter. Understandings of humanity’s place in nature tended to follow the same pattern: whether we’re being made out of corn by the gods of the Popul Vuh so we can “keep the days” or being given command over all the other animals by Yahweh, we like to see ourselves as being kind of a big deal in the grand scheme of things.

Giordano Bruno, a renegade sixteenth-century monk from the Kingdom of Naples, stands out as a true eccentric in this regard. Even today, his ideas sound slightly crazy: just last spring, in fact, I befuddled a lunch table of distinguished scholars at the Huntington Library by inadvisedly bringing up Bruno’s “alien Jesus” theory.

Let me explain.

In his 1584 book On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, Bruno theorized that

there is a single general space, a single vast immensity which we may freely call Void; in it are innumerable globes like this one on which we live and grow. This space we declare to be infinite… In it are an infinity of worlds of the same kind as our own.

This was controversial, but it wasn’t grounds for being declared a heretic. However, Bruno crossed a line when he followed his argument to its logical conclusion: if there are an infinity of worlds, and if some worlds have sentient beings created by God, then wouldn’t these planets also need to be saved by the personification of God? By, well, alien Jesuses? (Bruno, its important to remember, wasn’t an atheist—just a highly unconventional Christian).

Bruno expressed the idea in strong terms: “The Supreme Ruler cannot have a seat so narrow, so miserable a throne, so trivial, so scanty a court, so small and feeble a simulacrum” as our earth alone, he scoffed. Instead, Bruno argued that God must be “glorified not in one, but in countless suns; not in a single earth, a single world, but in a thousand thousand, indeed in an infinity of worlds.”

Giordano Bruno was burnt at the stake in 1600 in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori, where his famous memorial statue now stands.

Now that – essentially the theory of an infinite number of intelligent beings worshipping an infinity of extraterrestrial Gods that are the various incarnation of the one Supreme Being – is the sort of thing that got you burnt at the stake in the sixteenth century. Especially if you were a touchy, sarcastic Neapolitan. And so it came to pass.

As the noted historian Ingrid D. Rowland reports in her book Giordano Bruno: Philosopher/Heretic, a fellow monk reported Bruno to the Venetian Inquisition for a number of heretical claims, including “that there are many worlds, and all the stars are worlds, and believing that this is the only world is supreme ignorance.” Its worth noting that the monk, Fra Celestino, was according to Rowland a bit “mad” himself. Among other things, he also claimed that Bruno believed “that Christ is a dog cuckold fucked dog” (yes, that’s the actual translation) that “Moses was a shrewd magician,” and “that Cain was a good man, and that he was right to kill Abel.” There was definitely some inter-monk backstabbing going on here, but the Inquisitors interviewed many others who corroborated Bruno’s eccentric views about the nature of the universe, and he was ultimately burnt to death on February 17, 1600.

In fact, though, what Bruno was proposing was actually the feel-good variant of our modern vision of the cosmos. Its fun to believe in aliens, especially if we believe that they are essentially like us. Our own history as a species becomes part of a greater story that gives meaning to our existence. As Ortberg’s piece highlighted, it’s a lot less fun to believe that we’re matter which randomly became sentient amidst an endless void interspersed by icy rocks and balls of shrieking gas.

Artist Jed McGowan recently commemorated the Voyager probe’s journey out of our solar system with a beautiful series of illustrations that evoke this fundamentally lonely vision of space:

After awhile, you can’t help but empathize with Voyager and admire its WALL-E-esque pluck in the face of adversity, doing its thing out there in the empty wastes:

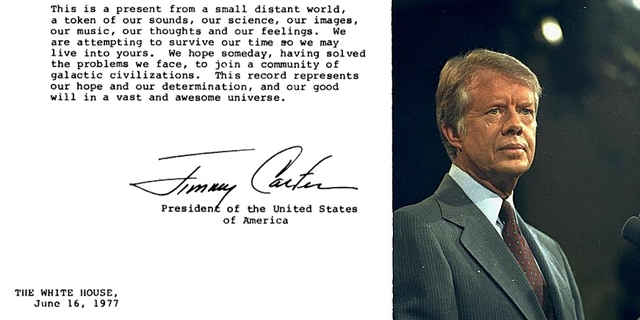

Strapped onto Voyager is a letter, a message that its conceivable to imagine being the last surviving artifact of the entire human species (if we accidentally blow up the solar system, say). The author of that letter was effectively serving as the spokesman for every human who has ever lived. If extraterrestrial life ever finds and decodes the message as intended, they may well assume that he was one of the greatest beings of Planet Earth, a paragon of our species and of all that we stand for.

His name was Jimmy Carter.

“This is a present from a small distant world” to an “awesome universe,” Carter wrote in 1977, ever the courteous Southerner. Star Wars had hit theaters a couple months before, and you can detect its influence in the President’s choice of words: “We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations,” he enthused. Carter also assumed the mantle of cosmic DJ, inviting any beings who found Voyager to give its golden LP a spin.

But what happens if there are no other civilizations, no alien Jesuses, no man-bats on the moon (as one 1830s hoax claimed), not even any squiggling strands of RNA or single-celled organisms floating in the primordial seas of some other pale blue dot? Does empty space have a history? Or does history only begin when sentient beings push back against the void?

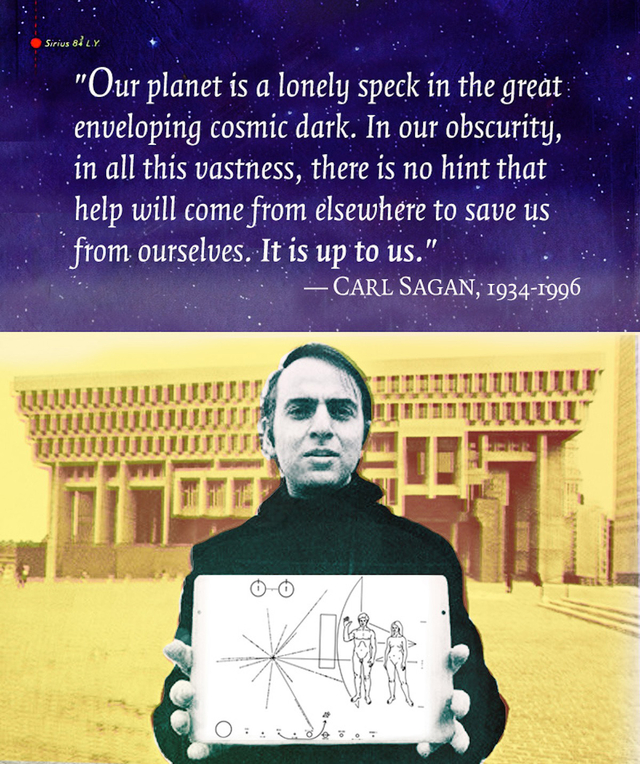

Perhaps we can imagine Voyager as an emissary not only of the human species, but of history itself. By being a human artifact made in a particular place and time—the summer when Luke Skywalker hit theaters, Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night” was a hit, and Carl Sagan and Anne Druyan were falling in love—Voyager is a mobile bubble of history.

Carl Sagan holding the plaque he made for the Pioneer space probe (1972), a forerunner to the Voyager Golden Record. Benjamin Breen/The Appendix

If the Elon Musks of the world succeed, others will be joining it soon. History’s sphere will expand outside the Earth, and maybe someday outside the Solar System. Anywhere humans or human objects go, we leave traces that will become part of an ever-expanding past.

For now, though, the only material artifacts of human history out there in the void beyond Pluto are a hopeful letter from a Georgia peanut farmer and a mixtape from the 70s.

Keep on trucking, Voyager.