That Time Lenin Played the Theremin

When we were putting together our third issue, ‘Out Loud,’ we kicked around ideas on how to bring in electronic music in one article, and state surveillance in another. We foolishly missed the most obvious choice, a prime mover of both: Leon Theremin, or Lev Sergeyevich Termen (1896-1993), the creator of the ghostly, ethereal theremin, the ur-instrument of electronic music.

To wit: Lenin was a natural at the theremin, it turns out, and the Soviet State loved its creator so much that it imprisoned Leon Theremin in a secret Gulag laboratory to develop eavesdropping devices.

When Theremin left Russia in 1989, after 51 years under state arrest, employment by the KGB developing electronic eavesdropping devices, and work developing further electronic instruments, he gave a fascinating interview with a musicologist named Olivia Mattis, available, at Thereminvox.com, which details Lenin’s reaction:

Mattis: What did Lenin think of it, and why did you show it to him?

Theremin: In the Soviet Union at that time everyone was interested in new things, in particular all the new uses of electricity: for agriculture, for mechanical uses, for transport, for communication. And so then, at that time, when everyone was interested in these fields, I decided to create a musical use for electricity. I made a few first apparatuses that were made [based on principles of] the human interference of radio waves in space, at first used in [electronic] security systems, then applied to musical purposes. I made it, and I showed it at that time to the leaders. There was a big electronics conference in Moscow, and I showed my instruments there. It made a big splash. It was written up in the literature and the newspapers, of which we had many at that time, and many doors were opened [for me then] in the Soviet Union. And so Vladimir Il’yich Lenin, the leader of our state, learned that I had shown an interested thing at this conference, and he wanted to get acquainted with it himself. So they asked me to come with my apparatus, with my musical instrument, to his office, to show him. And I did so.

Mattis: What did Lenin think of it?

Theremin: I brought my apparatus and set it up in his large office in the Kremlin. He was not yet there because he was in a meeting. I waited with Fotiva, his secretary, who was a good pianist, a graduate of the conservatory. She said that a little piano would be brought into the office, and that she would accompany me on the music that I would play. So we prepared, and about an hour and a half later Vladimir Il’yich Lenin came with those people with whom he had been in conference in the Kremlin. He was very gracious; I was very pleased to meet him, and then I showed him the signaling system of my instrument, which I played by moving my hands in the air, and which was called at that time the thereminvox. I played a piece [of music]. After I played the piece they applauded, including Vladimir Il’yich [Lenin], who had been watching very attentively during my playing. I played Glinka’s “Skylark”, which he loved very much, and Vladimir Il’yich said, after all this applause, that I should show him, and he would try himself to play it. He stood up, moved to the instrument, stretched his hands out, left and right: right to the pitch and left to the volume. I took his hands from behind and helped him. He started to play “Skylark”. He had a very good ear, and he felt where to move his hands to get the sound: to lower them or to raise them. In the middle of this piece I thought that he could himself, independently, move his hands. So I took my hands off of his, and he completed the whole thing independently, by himself, with great success and with great applause following. He was very happy that he could play on this instrument all by himself.

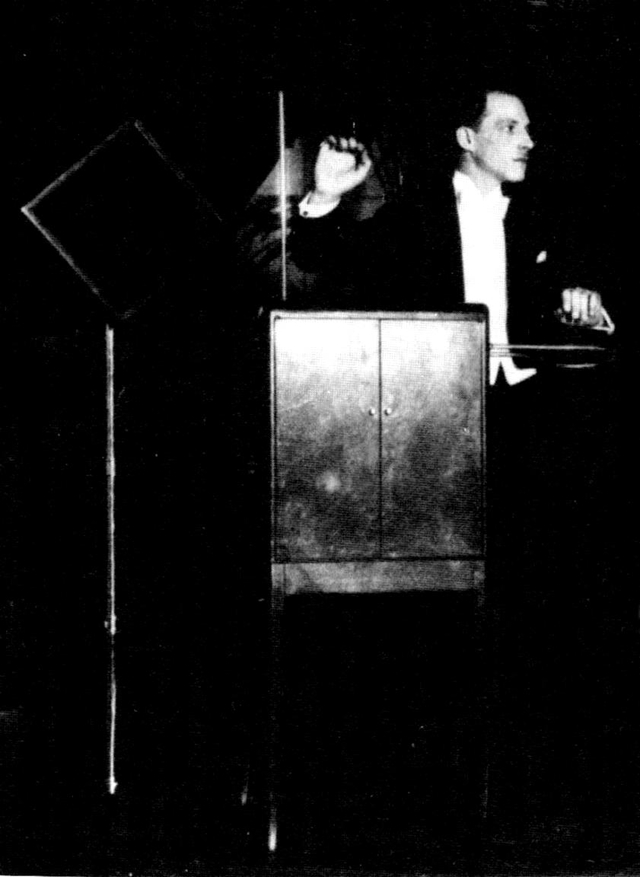

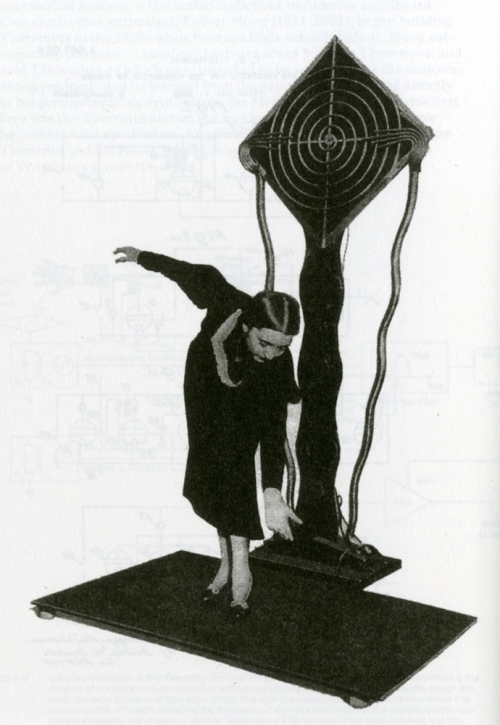

Mattis’s entire interview is excellent, touching on Theremin’s invention of his famed instrument in 1920, and his “Terpsitone,” an instrument for dancing.

The interview also covers Theremin’s return to the Soviet Union from New York in 1938. It had been rumored that he was kidnapped by Russian spies, but Theremin suggests it was at his own behest. He indeed was sent to a work Gulag for many months, and he ended up imprisoned in a laboratory developing listening devices for eight years. Theremin was awarded the Stalin prize for his espionage work in 1947.

A very young revolutionary Joseph Stalin—perhaps ready to time-travel to Williamsburg, Brooklyn ca. 2008, and play theremin in his new band?

Theremin disappeared from the international public eye during this period. One book even claimed he had died in 1945. His return to the West in 1989 was clearly an important moment for him, as Mattis’s interview suggests. Their conversation closed on a suitably ambiguous note. Theremin, perhaps better than anyone, had been attuned to what he could and could not say, and how discordant the true story of his imprisonment could sound, after years of silence:

Mattis: Do you have a message, now, in 1989, that you would like to convey to the Western World?

Theremin: What words! I knew the Western world pretty well. I haven’t been ever– Only here I see some of my friends, so I don’t know to whom to say anything. The only thing I wanted to ask, maybe of some people (if it were allowed by the Soviet government), is that I be allowed to promote my instruments. You must make the impression that I came here– that I was allowed to come here. It seems that there will be no punishment for me if write in the newspaper about all I have told you. I hope– We’ll see what happens. The same with my invention. I want to stress to you that all this needs to be done in a disciplined way, and that when people will be asking about me and writing about me, that all this be done in a responsible way. But if you write that I have said something against the Soviet government and said that it is better to work elsewhere, then I shall have difficulties back home. [ironic laughter]

He died four years later.

Hat tip to Joan Neuberger for bringing that fantastic interview to The Appendix’s attention. She was alerted to it by the people at The Calvert Journal, which covers “creative Russia,” and last month ran a review of “Sounding the Body Electric,” an “exhibition of East European sonic innovations from the Fifties to the Eighties” in London.