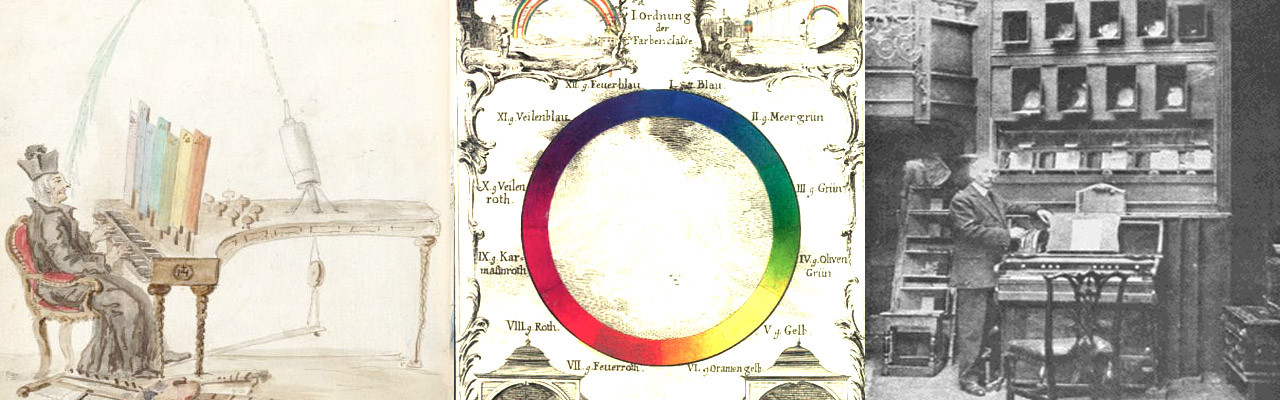

Castel’s ocular harpsichord (1750s), a 1771 engraving of his theories, and Rimington's color organ (1891).

Castel’s ocular harpsichord (1750s), a 1771 engraving of his theories, and Rimington's color organ (1891).

Exploring Music and Color in Nineteenth-Century France

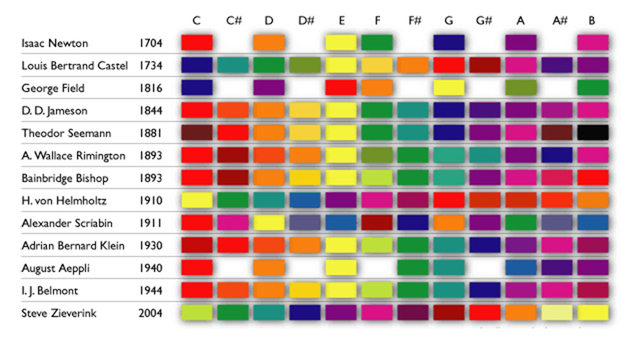

While researching *The Appendix’s previous issue “Out Loud”, devoted to music and sound, we grew interested in a related topic: that of synesthesia. How do sound and color fit together, and why do some minds draw intensely vivid connections between the two? Lawrence E. Marks’* The Unity of the Senses, for instance, described Newton’s belief in “a real analogy between elementary colors and the notes of the musical scale.” Newton’s prism experiments famously established the ROYGBIV rainbow of colors which combine into white light—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. But for Newton (as for other Enlightenment thinkers) the seven colors also corresponded to the seven notes of the musical scale.

We poked around the Internet looking for more information, and found useful resources like this chart by Fred Collopy, which visualizes three centuries of claims about the relationship between music and color:

Yet so much of what is available about sound and color online restricts itself to pointing out the inherent coolness of synesthesia and leaves it at that. Luckily, Gina Rivera, who recently received her PhD in historical musicology from Harvard, offered to fill in the blanks.

—The Editors

In my previous Appendix post “Music and Color: the French Connection,” I surveyed the work of mathematician and color-keyboard mastermind Louis-Bertrand Castel. Despite skepticism from the public, Castel was eventually recognized as the architect of one of the first successful projects to build plays of color and light into a working musical instrument. I now turn from Castel and his ‘color clavichord’ to his successors in the nineteenth century who explored new musical harmonies.

The principal voices in early debates about tonal music were the mathematician and musicologist Alexandre-Étienne Choron and the collector, archivist, and musicologist François-Joseph Fétis. As they turned from the interplay of light and music to critiques of the history of sound, they explored notions of musical color that were far more complex than any bolt of blue emitted from a keyboard. The ideas they explored have loomed large in musicology ever since, including the relationship between audiences and experimental musical works, the dialogue of performance with criticism, and the idea that musical progress — from increasingly complex tonal colors to new uses for instruments, from chromaticism to atonality — has its own particular joys and sorrows.

The musicologist Emily Dolan has recently pointed out that the concept of timbre launched a rich vocabulary for evaluating the beauty of musical sound in the eighteenth century: it drew into sharper focus the idea that the expressive value of music depended on its sonorities. Later commentators associated timbre ever more strongly with color and the idiosyncratic sounds of particular instruments, paving the way for modern theories of orchestration.

Choron and Fétis seized on tonality and tone color alongside warnings that the perfection of modern music risked passing into decline. They voiced what Brian Hyer has described as the inherent unease of a musical aesthetics that privileges the new. Increasingly, composers and listeners came to fetishize dissonance or harmonic color as heralding either progress toward a utopian emancipation of sound or a collapse into a musical apocalypse. Color or tone color became a sticking point like no other: it held the keys to musical perfection and pleasure but could also lead to the destruction of music itself.

It was only one year after the French Revolution that Choron began dedicated work on a translation of the Gründliche Anweisung zur Composition (1790), the disquisition on composing by Johann Georg Albrechtsberger. In a citation early in the translation, Choron calls attention to the distinction between tonalité antique (“ancient tonality”) and tonalité modern (“modern tonality”). For Fétis, the difference arose from the early modern reliance on dominant seventh harmonies. This was the dominant seventh that Choron had described as the invention of the baroque madrigalist and priest Claudio Monteverdi, who also composed works of sacred music and opera.

While a number of subtle differences distinguish Choron’s from Fétis’s account of tonality and its history, these authors both remained interested in the ordering of pitches within the musical scale — something that surely would have summoned thoughts of earlier analogies between the color scale and its musical analogue. They also emphasized the expressive ramifications of the relationship between distinct harmonies and the workings of consonance, dissonance, tension, and resolution.

At this point in the post-Revolutionary decades, eighteenth-century tonal theory still lingered in collective consciousness. The composer and theorist Jean-Philippe Rameau had described the tonic as something of a magnet, attracting other harmonies as well as the listener’s attention, whereas the mathematician and philosophe Jean Le Rond d’Alembert took a page from the music theories of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, waxing somewhat coloristic in his references to the aigreur du triton (“sourness of the tritone”) and the état doux (“sweet state”) of consonance. The emergence of the concept of timbre in the eighteenth century implied a new awareness of music as an expressive medium: even the collective of instruments and players making up the orchestra came to be understood as an engaging, autonomous entity dedicated to the production of expressive, colorful sounds. At the same time, Choron and Fétis both spoke to early Romantic concerns that chromaticism and rich tonal color were never necessarily good things.

Indeed, what we often describe in Schoenbergian terms as the emancipation of dissonance — the progressive shift toward greater chromaticism, striking timbre and color, and disharmony — numbered among the concerns of an earlier generation as well. Choron and Fétis worried that harmonic experimentation spelled disaster for the future of music as they knew it. Choron bases his account of tonality on the idea that the cultural ethos of each historical age is something that we can actually hear in its music, that the reigning tonalité moderne and its perfected state marked the current age for success but could not assure that tonality could keep from passing into decline and destruction. Fétis speaks in one passage of his Traité complet de la théorie et de la pratique de l’harmonie (1844) of the disturbing loss of melodic purity that resulted from any excess modulation, of what danger lurked in the symphonic and operatic repertories of Rossini, Berlioz, and Wagner if their désir insatiable de modulations (“insatiable desire for key changes”) or their attraction to jarring tonal effects was followed to its logical conclusion. Music might not only change: it might become something no longer recognizably musical.

In the decades between Castel and these later authors, the French fascination with musical color shifted from practice to theory, from the scientific and organological interests that brought the ocular harpsichord into being all the way to the scholarly and ideological construction of tonality, in which theories of musical color played a crucial part. Modern audiences maintain ties to an enthusiasm for combining sensory media that dates to the long eighteenth century: to the early synesthetic fantasies of Castel and to the symphony of metaphors for musical growth, decline, tension, release, absorption, and enjoyment in the writings of Choron and Fétis.

Recommended Links

- Emily Dolan, The Orchestral Revolution: Haydn and the Technologies of Timbre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- The Museum of Imaginary Musical Instruments

- The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Arnold Schoenberg, Style and Idea: Selected Writings, 60th Anniversary Edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).