Captain Cook’s outsized life was enshrined in a miniscule memento.

Captain Cook’s outsized life was enshrined in a miniscule memento.

The Miniature Coffin of Captain Cook

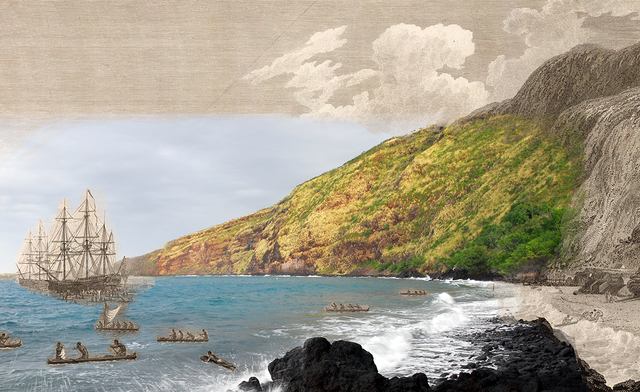

Kealakekua Bay is a verdant cove on the Kona Coast of Hawai’i, its electric blue waters teeming with sea turtles, corals, anemones, puffers, and moray eels. It must have presented an appealing prospect for the ragged band of sailors who gathered on its shore to repair a broken ship mast in January of 1779. These men were the crew of the famous circumnavigator Captain James Cook, and their captain would not leave the beach alive.

As Richard Holmes notes in The Age of Wonder, Cook’s three Pacific expeditions played a profound role in world history: his accounts of Polynesian cultures influenced Romanticism and inspired writers and artists ranging from Melville to Gauguin. Meanwhile, Cook’s dashing young botanist Joseph Banks carried back samples of flora and fauna that revolutionized the nascent fields of botany and biology (Banks also excitedly recorded the “wonderful scene” of Polynesian youths who skimmed along the crests of waves “with incredible swiftness”—the first European description of surfing.)

By the end of Cook’s third voyage in 1779, however, earlier impressions of Polynesia as a heaven on earth had grown more complicated. Veneral disease was already beginning to take a toll on island populations, sailors were growing restless, and even the normally steadyhanded Captain Cook had begun to act erratically. Recounting events in an official report, Cook’s lieutenant James King wrote that he “firmly believed matters would not have been carried to the extremities they were, had not Capt. Cook attempted to chastise a man.”

An historical mash-up of the bay, merging a 1795 engraving by John Webber with a contemporary photograph. The author/Wikimedia Commons

Initially, according to King, Cook and his officers were accepted as friends by the leaders of the island. A group of priests even visited, who “carried wands tipped with dog’s hair” and “tabooed the place where the mast lay, sticking their wands round it” to mark it as a place of safety. Tensions mounted, however, after a series of misunderstandings between Hawaiians and the crew, culminating with a local man named Pareea being “knocked down by a violent blow upon his head with an oar.” In response, the crowd surrounding Cook’s men began pelting them with rocks, forcing them into the waves.

Pareea had by this time recovered from the blow and (to his credit) actually began calling for peace, but it was too late. Although Captain Cook hadn’t been present for the altercation, he considered it an affront to his honor that called for “violent measures.” The next morning, King found “Captain Cook loading his double-barrelled gun” along with a group of “armored marines.” Soon after dawn, Cook and the marines set off across the bay in a small boat and entered the village of Kowrowa, where Kalaniʻōpuʻu, the King of Hawaii, happened to be staying. Cook paced angrily through a gathering crowd of locals and drew within thirty yards of the “old king.” A tug of war over the king ensued, with Cook attempting to kidnap him by force, and the king’s advisors fighting back “at first with prayers and entreaties, but afterwards having recourse to force and violence.”

In the confusion, a high-ranking Hawaiian noble named Kalimu was shot, and the violence escalated rapidly. The villagers took up their weapons and armor and charged Cook and his crew. The marines surrounding Cook had far superior weaponry with their flint-lock muskets, but no room to maneouvre and no time to fire, and four were killed almost instantly. Cook retreated to the shore, but was hit over the head with a club and then repeatedly stabbed. He died in the surf.

_may_have_been_chief_who_killed_cook-medium.jpg)

Anonymous 1830s copy of a painting by John Webber, “A Man of the Sandwich Islands with His Helmet.” This is believed to be a portrait of Kanaina, one of the Hawaiian chiefs who killed Cook. Wikimedia Commons

After his death, Cook’s second-in-command Charles Clerke assumed control of the British forces. He attempted to win back Cook’s body for burial, but the Hawaiian priests told him that Cook’s corpse had been ritually baked, the flesh stripped from the bones, and the remains deposited in a sacred place. Although Cook had aroused the ire of King Kalaniopu’u and his people, they still regarded him as a powerful chief whose bones were potent sources of mana, or spiritual power. (See anthropologist Marshall Sahlins on the religious context for Cook’s death and burial).

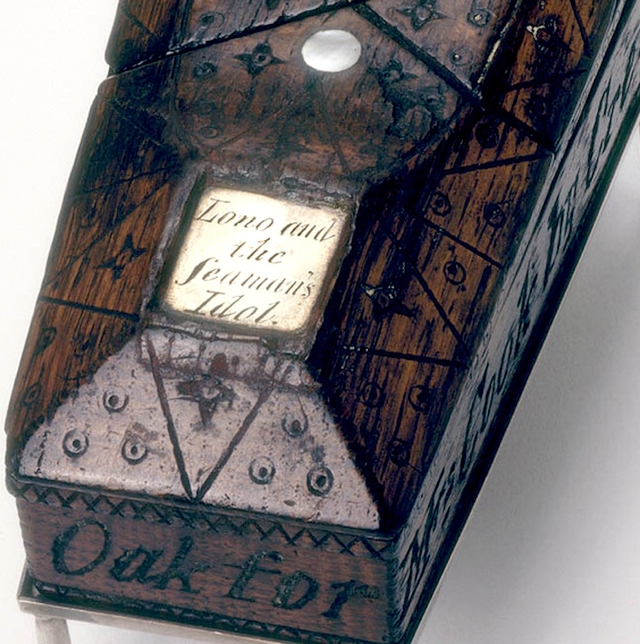

A remarkable artifact owned by the State Library of New South Wales in Australia confirms that Cook’s men also venerated his mortal remains. This small, intricately-carved coffin was created by an anonymous craftsman on Cook’s ship, the HMS Resolution, during the return journey from Hawai’i to Britain.

It features a number of striking details: the top lid swivels open in two pieces, revealing a watercolor painting of Cook’s death on the beach and, below that, a lock of his hair.

A silver plate set into the base of the box reveals that the wood itself had once been part of the ship (and that the box was a memento mori intended for Cook’s widow): “Made of Resolution oak for Mrs Cook by crew.” There’s also a curious detail: another silver plate offers up the cryptic inscription “Lono and the Seaman’s Idol.”

In the 1820s, a missionary in Hawaii named Hiram Bingham encountered a legend about the god Lono which he believed was inspired by what transpired at Kealakekua Bay. It was the belief of Cook’s crew and that of later Europeans on Hawaii that Cook had become a enshrined for eternity as a Hawaiian demigod. (As a side note, Bingham’s grandson would become enshrined as well: he was the inspiration for Indiana Jones).

What became of Cook’s bones is a mystery—as is the truth of European assumptions about his deification in Hawaiian lore. But Cook’s coffin will forever stand as an extremely tiny memorial to the sea captain’s death on that sunny Hawaiian beach.

Read more about the coffin at its final resting place, the State Library of New South Wales.