“The area around its eyes is always turquoise.”

“The area around its eyes is always turquoise.”

The Emperor’s Turkey

Turkey doesn’t exactly give off an exotic aura today. But four hundred years ago, the North American native was the talk of Europe and Asia. The above image is from seventeenth-century India - 1612 in Agra, to be precise. The Mughal Emperor Jahangir ordered it painted because he found his new pet to be so “extremely strange” that it warranted extensive description in the official chronicle of his reign:

Sometimes when it displays itself during mating it spreads its tail and its other feathers like a peacock and dances. Its beak and legs are like a rooster’s. Its head, neck and wattle constantly change color. When it is mating they are as red as can be. You’d think it had all been set with coral. After awhile these same places become white and look like cotton. Sometimes they look like turquoise. It keeps changing color like a chameleon.

The opium-addicted, artistically inclined emperor was an animal lover, and he kept this turkey (a gift from the Portuguese viceroy) in his private bestiary. Judging from his detailed appreciation of the turkey’s aesthetic virtues, we can guess that it numbered among Jahangir’s favorite exotic beasts.

The complete painting of Jahangir’s turkey, created by famed Mughal artist Ustad Mansur. The Jahangirnama

Around sixty years later, the bird had become familiar enough to appear in an English cookbook with the wonderful title The Way to Get Wealth. “Slice good store of Onions,” add “good sore of Gravy that comes from the Turky, and boyl them very well together” with water, pepper, salt, breadcrumbs, sugar, and vinegar, the book advised. “And so serve it up with the Turky.” Alternately, you could mix “the blood of a Swan” with “stewed Prunes,” then boil it with sugar and cinnamon and serve.

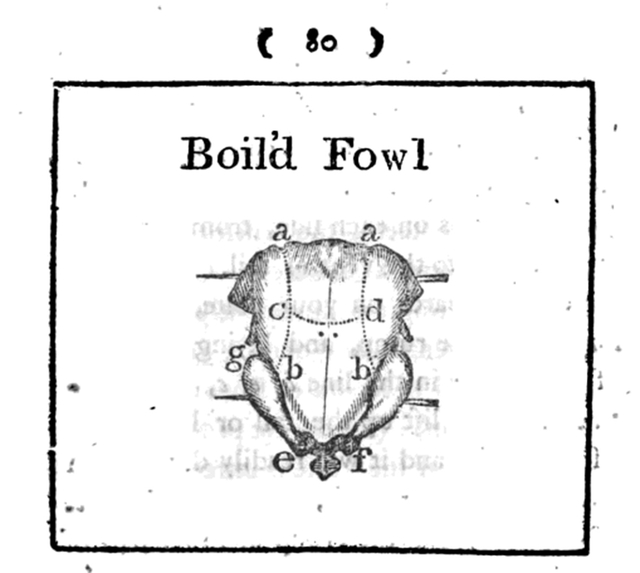

A 1791 book called The Honours of the Table had moved toward a more modern approach to turkey consumption, advising that it be “roasted or boiled,” then “trussed up and set up to table like a fowl… The best parts are the white ones, the breast, wings and neckbones.”

The original exotica nature of the American turkey in the Old World is retained in its name, however. It is so called in English because British consumers guessed that the strange new bird might hail from the Islamic east, which was usually lumped together under the generic name “Turkey” in the seventeenth century. (That’s my theory, at least - linguistics professor Mario Pei raised the possibility in discussion with Radiolab’s Robert Krulwich that the birds may have been shipped to London via Istanbul, hence the name). At any rate, a similar phenomenon is at work in the French name for the bird, dinde, short for “coq d’Inde” or “Indian rooster.” Things get even more complicated in Portuguese, where the bird is simply called “Peru”! This, however, is closer to being on the right track: the turkey’s native range extends from the Valley of Mexico to New England and Canada.

In other words, its clear that early modern eaters developed a taste for the bird’s flesh well before they had any real clue where it came from. Maybe there’s a commonality there - because we don’t really know where our factory-farmed turkeys come from either.

More on the fuller import of Jahangir’s turkey to come (you can read my preliminary thoughts about what the story can tell us about globalization at my blog, Res Obscura. But for now, happy Thanksgiving.