Tipu Sultan was not quite Westernized enough for Ruffin’s liking.

Tipu Sultan was not quite Westernized enough for Ruffin’s liking.

An Indian Merchant in Marseilles, 1792

If he hadn’t gotten sick, you might have already heard of Ahmed Khan.

Sometime in 1792, too weak to finish the last leg of a journey from Bombay to London, the Indian merchant and money-lender was abandoned by his traveling companion, left to recover or die alone in Marseilles. The port was a cosmopolitan commercial hub, but it didn’t see many ailing South Asian businessmen. Local officials were on high alert for counter-revolutionary agents and foreign spies; someone as conspicuous as Ahmed couldn’t go unnoticed. Unable to resist, and maybe grateful for the help, he became a patient/prisoner of the local government, whose agents awaited the arrival of a special envoy from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Ahmed did not speak French—yet—but he did speak Persian, then the language of diplomacy, poetry, and prestige throughout the Subcontinent. So did Pierre Ruffin, the French government’s official translator of ‘Oriental’ languages, which, at the time, meant Arabic and Persian. Ruffin, who had survived the fall of his former employers, had been in office for over a decade. His moment of glory had come in 1788, when an embassy from Tipu Sultan, ruler of the southern Indian state of Mysore, arrived in Paris to seal an alliance against Britain.

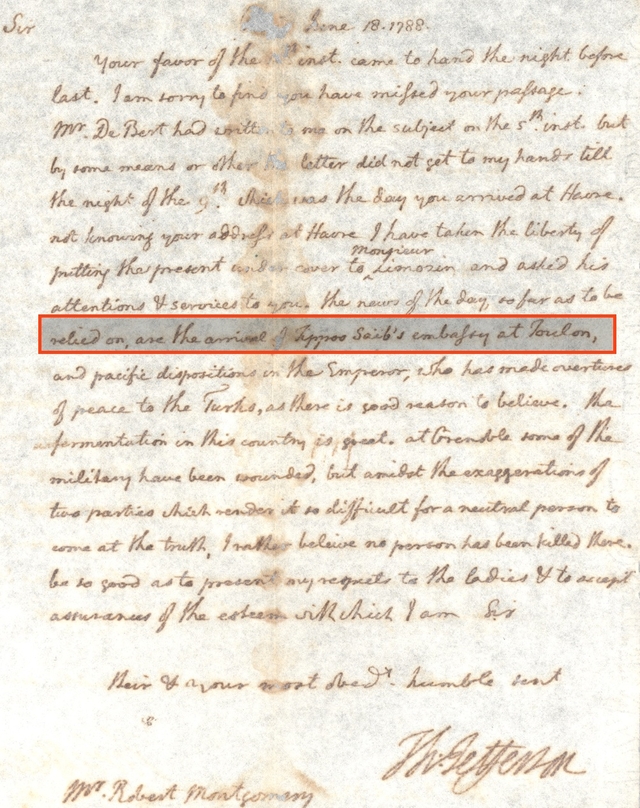

Thomas Jefferson mentioned the embassy from Tipu Sultan in a letter from June 18, 1788. Thomas Jefferson to Robert Montgomery, Jefferson Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.

The monarchy, cash-strapped and already collapsing, sent them away with platitudes and a lovely porcelain set (stolen by British soldiers in 1799, many of these pieces are now housed in Powis Castle in Wales), but Ruffin had briefly shone at the center of court life thanks to his language skills. Ahmed presented Ruffin an opportunity not only to make himself useful to France’s new republican government, but also, the translator imagined, to make history.

Ruffin introducing the Mysorean embassy to the Duchess of Orleans, 1788. gallica.bnf.fr Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Ahmed would have made history in any case. In 1790, fed up with the East India Company’s refusal to help him collect outstanding loans owed to him by British traders in Bombay, he departed for London to sue them on their own turf. This would not have been the first time British crimes in India had been tried before a metropolitan court. The prosecution of Warren Hastings had held London’s attention throughout the previous decade, as Edmund Burke, in high dudgeon, read the written testimony of Indian notables against the corrupt former governor of Bengal. But British law had never seen an Indian come to London to initiate such a suit himself. Ahmed Khan must have been a big player in Bombay, with money enough to loan large amounts to British traders and courage enough to demand repayment.

Or maybe it was foolishness. He traveled with only one companion, who seems to have abandoned him without a backward glance. Alone, sick, and vulnerable, Ahmed was taken hostage by a revolutionary government that had not even existed when he began his journey.

In a letter dated August 3, 1794, Ruffin issued his first and only report on Ahmed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He explained that he had brought Ahmed to Versailles and placed him under personal supervision. Since I’ve never been able to find any trace of Ahmed’s existence outside of this report and its official response, it’s impossible for me to say if Ahmed went willingly, or if, in his condition, willing was something he could do.

Apparently acting on his own initiative, Ruffin nursed Ahmed to health and taught him (under duress?) how to read and write French. To prove that the government had not wasted its money by keeping him alive, Ruffin made his pupil translate into Persian the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, one of the French Revolution’s founding documents. As befit a cultivated Muslim gentleman, Ahmed seems to have been an expert in calligraphy. Ruffin praised the penmanship of Ahmed’s Persian manuscript, attaching it to the report as a certificate of his pupil’s good behavior.

The Foreign Affairs desk wrote back in raptures, asking for a duplicate copy and promising that Ahmed’s work “will be preserved forever as a precious monument.” It has disappeared without a trace.

As has Ahmed: whether he died of his illness, continued his journey, returned to Bombay, or settled in France, he disappeared from the record, no longer of interest to French officialdom, or, it seems to Ruffin, his former caregiver, teacher, and warden. Ahmed and his manuscript had been briefly of interest to them as a symbol—but of what?

Tipu’s Tiger, a mechanical musical instrument created for the sultan to celebrate his victories over the British. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

One would expect an answer along the lines of ‘the universality of republican principles,’ or ‘France’s enlightened (and Britain’s shabby) treatment of non-Europeans.’ Both of these were common themes of French revolutionary propaganda, but neither mattered to Ruffin. He was simply amazed that Ahmed, a Muslim, an Asian, could “write in French letters.” He had never seen one who could learn to write in a Western script, and had assumed they were simply incapable of doing so. Indeed, left to their own devices, he suggested, they probably were—but Ahmed was a “conquest of philosophy.”

Thanks to his French military advisers, Tipu Sultan, France’s not-quite-ally in Mysore, had been the first to show that “Muslim soldiers could be equipped with bayonets and drilled in the European manner.” But this had only been a superficial Westernization, an imitation of the European arts of making weapons and disciplining bodies. There had not yet been “a man born in their country, and preserving his faith, who would learn to read and write our language. This phenomenon has been reserved for the Republican era.” For Ruffin, Ahmed’s progress confirmed the superiority of republican government and European civilization, and showed that the former was the most effective means of spreading the latter among the less-advanced nations of Asia.

Liberty, Reason, and Justice introducing the Declaration of the Rights of Man, Ahmed’s homework. gallica.bnf.fr Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

In Ruffin’s vision, Asians like Ahmed could bear witness to the glory of the French Republic by espousing the principles enshrined in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Not that they could understand or endorse them—that possibility did not cross Ruffin’s mind. But simply in saying them, writing them, echoing them, France’s Asian tutelaries would testify that the Republic was a miracle-worker, capable of teaching its language to people until then excluded from Europe’s equivalent of Persian.

Ahmed risked so much to be heard by British justice, but his voice is lost to history. Ruffin and his ministerial superiors had no interest in what Ahmed might say for himself, only whether, like a rare parrot brought out for an after-dinner entertainment, he could repeat the few lines he’d been given. Even his translation seems to be lost, perhaps mis-cataloged somewhere in the French National Library’s collection of Persian manuscripts.

I came across Ruffin’s report while looking for something else in a volume of miscellanea at the archives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and now Ahmed is caught again in a story told by someone else.

Primary sources consulted: Archives du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, Courneuve. Mémoires et Documents, Asie, vol. 20, f 133-133v.