The album cover of Cybotron’s Enter (1983).

The album cover of Cybotron’s Enter (1983).

Technofy Your Mind: Cybotron and 30 Years of Detroit Techno

Techno is black music. True, there’s more to it, but that statement can be justified on both general and specific grounds. General: its genealogical forbears, whether it came of age in Europe, America or elsewhere, are Disco and Rock ‘n’ Roll, the black roots of which are not in dispute. Specific: the earliest releases of bona fide Techno—not to mention the genre name itself—came from four black dudes trying to imagine the future in inner-eighties Detroit. And if you want to get technical, you can throw in the foundational influence of Chicago’s mostly black inventors of Acid House, which together with the “Detroit sound” swept post-industrial Europe in the late eighties and created electronic dance music as we know it. None of which is to diminish the importance of such Euro-pioneers as Kraftwerk, Giorgio Moroder, and Gary Numan, or of Japan’s Yellow Magic Orchestra. But Americans often mistake modern Techno for a foreign import. It is not.

Preliminaries out of the way, let us now praise Cybotron’s Enter, released in 1983 and reissued last month by Fantasy Records. Enter is not really a Techno album. You see, it has guitar solos in it. But it is a Techno album. You see, it has the driving beats, the hollow snares, the squelchy bass lines, the sweeping atmospherics. Most of all, Enter is an unlikely album, the product of a Hendrix-riffing Vietnam vet collaborating with a precocious teenage futurist within the very specific context of deindustrializing, urban-crisis Detroit. There will never be another album like it.

The responsible parties are as follows. Rik Davis, born 1950 or thereabouts, alias “3070,” mind deranged by comics at an early age, perhaps traumatized by the ‘67 riots, “joined the Marines to sail the Seven Seas with Captain Sinbad,” deployed after Tet, saw action, discharged in 1971, “invested his post-malaria, combat-disability pay in an Arp synthesizer and programmed it to replicate machine-gun fire.” Juan Atkins, born 1962, aliases too many to enumerate including “Model 500,” “Channel One” and “Infiniti,” learned to play drums-bass-guitar at an early age, drove under the influence of Parliament-Funkadelic, became obsessed with synthesizers—“like UFOs landing on records”—circa 1978. They met in 1980 in an electronics class at Ann Arbor’s Washtenaw Community College.

The name Cybotron apparently had something to do with the anxious futurology of pop sociologist and management guru Alvin Toffler. Toffler is the kind of guy that intellectual historians like to make fun of. And there’s a reason for that. I don’t know how passages like this one from his bestselling Future Shock read when the book first appeared in 1970, but today they sound rather breathless and ridiculous:

Previously, men studied the past to shed light on the present. I have turned the time-mirror around, convinced that a coherent image of the future can also shower us with valuable insights into today. We shall find it increasingly difficult to understand our personal and public problems without making use of the future as an intellectual tool.

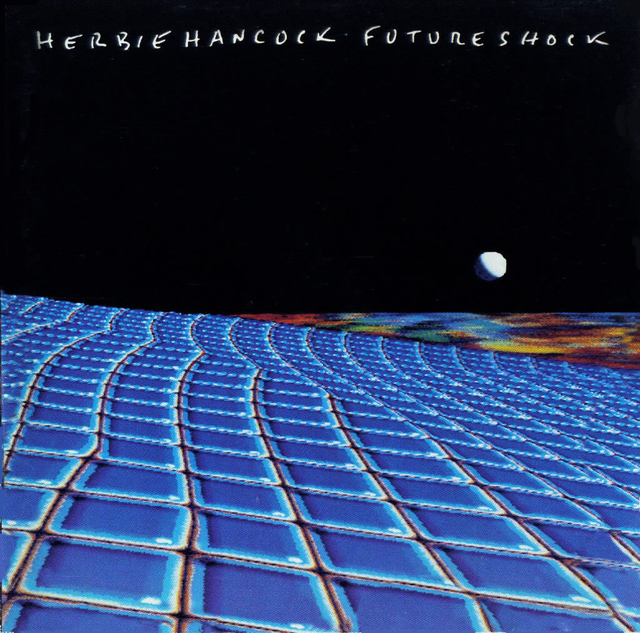

Still, Toffler knew how to turn a phrase, and Future Shock’s central thesis that the pace of social change is as important as the substance of the change itself is a respectable bit of sociological wisdom that receives more-or-less canonical treatment in Karl Polanyi’s classic, The Great Transformation, probably the single most important theoretical statement of the principles of social democracy after Keynes’s General Theory. It seems worth noting that the kind of change that was happening in Detroit when Cybotron came together at the dawn of the Reagan Era was just the kind of rapid social disintegration that Polanyi predicted would inevitably ensue if policymakers untethered the market economy from it social moorings. That plus residential racism. But, anyway, in the same 1983 that Cybotron released Enter, Toffler came up again in Herbie Hancock’s electro-funk-jazz excursion, Future Shock, which featured the Grammy-winning masterpiece of early hip-hop futurism, “Rockit.” So Toffler seems to have had a point when he wrote that, “in dealing with the future . . . it is more important to be imaginative and insightful than to be one hundred percent ‘right.’”

What did Enter offer in the images and insights department? Let us take a brief but comprehensive tour. The eponymous first song has to be the most agonized invitation to a party ever:

No transport out of here

I guess we have to put away our fear

Enter

Why don’t you . . .

Proceed to the gothic funk of “Alleys of Your Mind,” lyrically incomprehensible in parts, yet obscurely suggestive of war crimes:

Don’t tell what you see

. . . If you do what you’re told

Blame it on thought control

. . .

Alleys of your mind

Paranoia right behind

Next, a melancholy piano intro leads to “Industrial Lies” and a critical take on the neoliberal order:

My conservative reactionary friend,

The ends don’t justify the means you understand.

. . .

You buy the missile buy the laser buy the tank,

Evict the widow put the money in the bank.

You do it all,

In the name of economics . . .

Moving right along, “The Line,” a song that anticipates Public Enemy’s sardonic comment in “911 is a Joke” on the crumbling and racialized edifice of late twentieth-century American municipal services. “The Line” is all juxtaposition, a song about eternally standing around set over an angry guitar riff on top of a propulsive machine beat.

Life is a line,

Take a number.

Just one big line,

That’s all it is.

. . .

I got into line

And waited to see,

What the bureaucrat

Would do with me.

Then his ice cold eyes

Foretold my fate.

I knew I had arrived

An hour late.

“What’s that you say?”

“Uh, no jobs today?”

Before Whodini tried to “Escape,” before Tracy Chapman found a “Fast Car,” Rik Davis and Juan Atkins were wishing Motown back to the future. But we all know how that turned out.

And now, finally, mercifully, “Clear,” the track that invented modern Techno. “Clear” synthesizes the crisp and abstract sonic texture of Kraftwerk with the funky bass-line bounce of Parliament. The last track on an album that began with the guitar-driven “Enter,” it signals an ambiguous transformation from psychedelia to cyberspace—that term apparently coined just the year before in William Gibson’s “Burning Chrome”. “Clear” was an ambivalent vision, not really clear at all.

After “Clear,” Cybotron split up. Davis wanted to go in more of a rock direction and eventually did so with two albums released in the nineties under the Cybotron moniker. Atkins had different ideas. He thought that a track called “Nightdrive (Thru Babylon),” which he made largely on his own but that Davis helped complete, ought to be the next step. “You can’t come behind a record like Clear with a rock-n-roll record,” he would later say. A lot of the guys who returned from Vietnam, he thought, were stuck on Hendrix and the psychedelic rock that came out of the sixties. Davis “was like Jimi Hendrix on the synthesizer,” Atkins said. It wasn’t a bad thing, just not what he was trying to do.

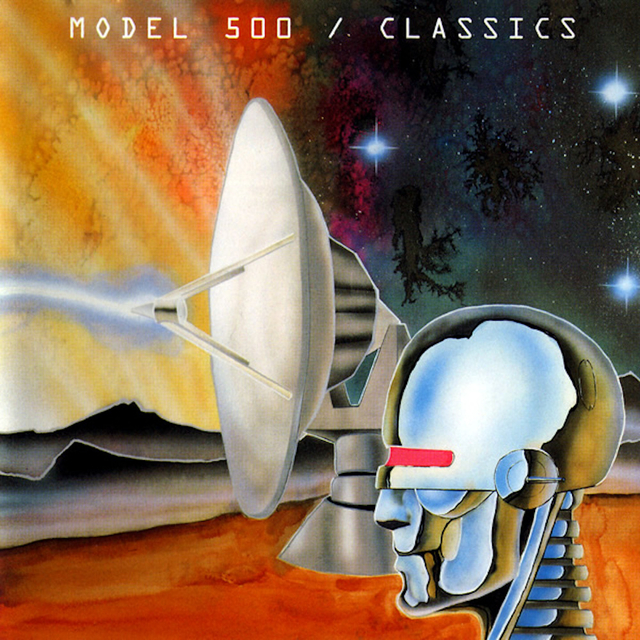

Atkins left Cybotron but took “Nightdrive” with him. He made another track, “No UFOs,” to back it and shopped the record to every label he could think of. No one would touch it. So he released the record himself on his own Metroplex imprint under the new name, Model 500. Both tracks, but especially the instrumental version of “No UFOs,” remain clearly, unmistakably, Techno: dark fascination with technology and the horizons of consciousness explored through artificial rhythm tracks and spacey synths. The tunes struck a chord. Three of Atkins’s friends—Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, and Eddie Fowlkes—joined him at Metroplex and together they developed the sound that Atkins had pioneered.

Like Chicago House, which was emerging at about the same time, Detroit Techno initially remained a regional style in the United States even as it exploded in Europe. In 1988 a British deejay and independent label boss named Neil Rushton worked with Atkins, May and Saunderson to put together the seminal compilation, Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit, which introduced Techno to British audiences and helped to formalize it as a genre. Rushton had been a key figure in the phenomenon known as Northern Soul: in the 1970s, working-class kids across Britain’s industrial North would come together for “all-nighter” bouts of feverish dancing to the sounds of obscure, high-tempo American R&B. As Northern Soul deejays crossed the Atlantic in search of still more obscure, high-tempo R&B records, they encountered various electronic dance music styles bubbling up in the black and Latino ghettos of high malaise-era America. Detroit Techno quickly got swept into the European rave culture that was sucking in other burgeoning American inner-city musical styles: New York Garage, Acid House, Electro, Freestyle, Miami Bass and, of course, Hip-Hop. Ten years later and much transmuted, all that stuff returned to hit Top 40 American radio via acts like The Prodigy, the Chemical Brothers, and Fat Boy Slim.

By that time, Juan Atkins had himself transmuted into the legendary “godfather” of Techno, playing packed megaclubs from Berlin to Tokyo and still producing innovative music. Not famous in a mainstream way, but no longer some weird black kid in penny loafers slinging Afrofuturistic dance tracks that nobody wanted to put out.

Meanwhile, new generations of Detroit Techno producers carried things forward. Carl Craig, Jeff Mills, Kenny Larkin and Robert Hood, the collective known as Underground Resistance, and the mysterious phalanx of pseudonymous projects generated by Gerald Donald and James Stinson: Drexciya, Shifted Phases, Transllusion, Dopplereffekt, Arpanet, Japanese Telecom, Elecktroids, Der Zyklus, Heinrich Mueller, Black Replica and who knows what else. The immensely influential Drexciya, whose members remained anonymous for years even to the curious, has one of the weirdest made-up backstories in modern popular culture. In 1997 the now defunct label Submerge, which was apparently connected to the Underground Resistance collective, put out a Drexciya compilation called the The Quest. The liner notes said this:

Could it be possible for humans to breath underwater? A fetus in its mother’s womb is certainly alive in an aquatic environment.

During the greatest holocaust the world has ever known, pregnant America-bound African slaves were thrown overboard by the thousands during labor for being sick and disruptive cargo. Is it possible that they could have given birth at sea to babies that never needed air?

Recent experiments have shown mice able to breathe liquid oxygen. Even more shocking and conclusive was a recent instance of a premature infant saved from certain death by breathing liquid oxygen through its undeveloped lungs. These facts combined with reported sightings of Gillmen and swamp monsters in the coastal swamps of the South-Eastern United States make the slave trade theory startlingly feasible.

Are Drexciyans water breathing, aquatically mutated descendants of those unfortunate victims of human greed? Have they been spared by God to teach us or terrorize us? Did they migrate from the Gulf of Mexico to the Mississippi River basin and on to the Great Lakes of Michigan?

Do they walk among us? Are they more advanced than us and why do they make their strange music?

What is their Quest?

These are many of the questions that you don’t know and never will.

The end of one thing…and the beginning of another.

Out - The Unknown Writer

Drexciya’s “Bubble Metropolis” makes me think that maybe futurism is always about plotting your escape from history. Cybotron’s Enter remains so special all these years later, when it has itself become history, because it looks both ways, back at what Walter Benjamin imagined as the “single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage” at the feet of the Angel of History, and forward toward a dream of techno-social utopia that, for being drenched in acid nightmares, is still fascinating and somehow hopeful.