The bizarre, Romantic, not-quite-scientific dinosaurs of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

The bizarre, Romantic, not-quite-scientific dinosaurs of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

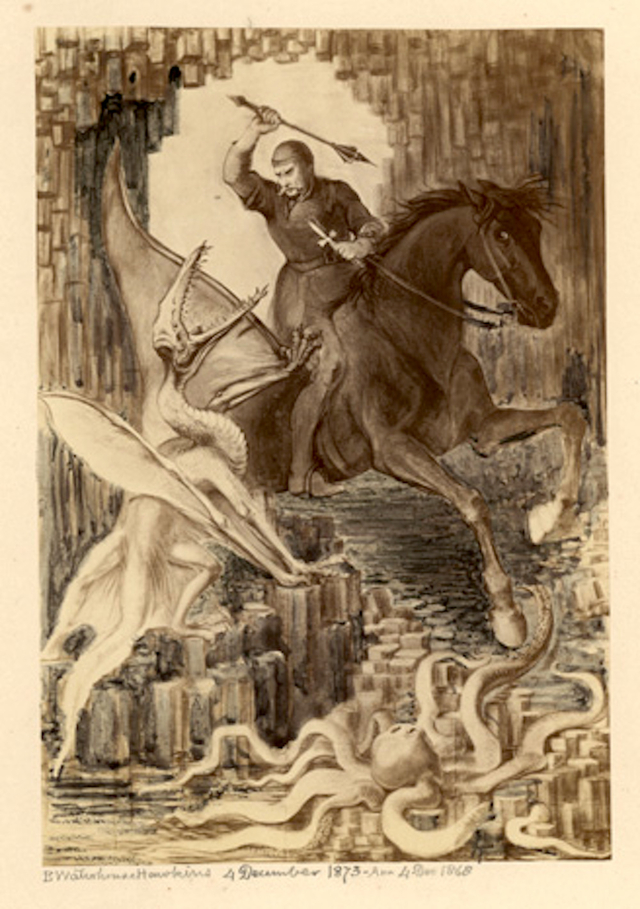

St. George and the Pterodactyl

In 1873, the eccentric illustrator Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins added a small sketch to his personal portfolio—a pen-and-ink drawing with the title “St. George and the Pterodactyl” scrawled across the bottom of the scene.

In this drawing, we see the famous knight engaged in a ferocious battle with a pterodactyl—the flying dinosaur that was discovered earlier in the century. It was a specimen that Waterhouse Hawkins, a self-taught paleontological illustrator, knew well.

St. George and the Pterodactyl B. Waterhouse Hawkins, 4 December 1873. Natural History Museum, London

Like much of Waterhouse Hawkins’s work, the drawing is challenging, fantastical, somewhat bizarre, and completely unexpected.

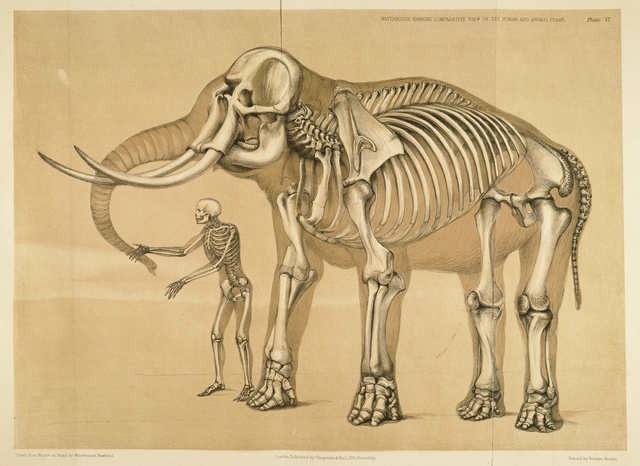

Hawkins’s Pterodactyl offers a window into the rapidly-changing world of Victorian natural history. No stranger to the challenges of reconstructing extinct animals, Waterhouse Hawkins’s other credits include the first sculptures of the Terrible Lizards, commissioned for the Crystal Palace between 1852-1854, as well as paleontological illustrations for the Smithsonian, Princeton, and the American Museum of Natural History. His drawings for A comparative view of the human and animal frame (London, 1860) are particularly striking:

“A comparative view of the human and elephant frame,” from Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, A comparative view of the human and animal frame (London, 1860) Wikimedia Commons

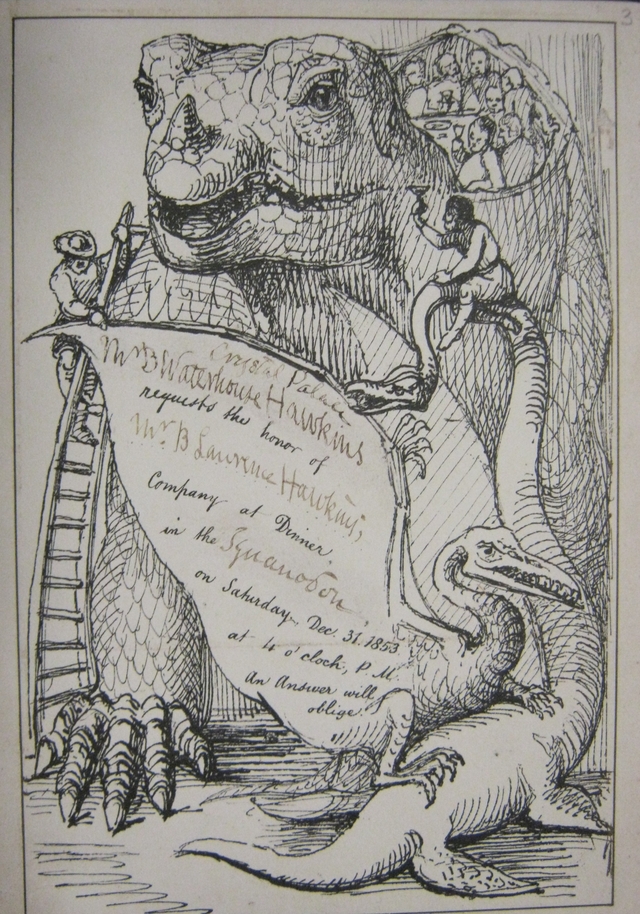

Hawkins’s playful invitation to Sir Richard Owen’s famous “dinner in the Iguanodon,” on New Year’s Eve, 1853, showed off his penchant for inventively juxtaposing the world of the dinosaurs with that of Victorian high society.

But what are we to make of Saint George’s combat with a fierce but extinct animal?

Traditional iconography of Saint George has several key components—an elaborate cosmological image with a clear narrative structure. The divine world at the top of the painting, surmounting the starry firmament. The spiritual warrior. Saint George’s holy crown. His horse. The dragon usually glowers in the lower right corner of the painting, trodden by the horse’s front hooves. Below the dragon, the dark caves of the lower world (Hell).

Most of these scenes feature a princess awaiting rescue. This was a distant echo from the Greek mythology of Perseus rescuing Andromeda from the wrath of the sea god, Poseidon.

By reading these paintings from top to bottom, we find a clear narrative grounded in a Christian cosmology that had remained largely constant from the time of Late Antiquity to that of Hawkins. The spiritual knight George “tames” (slays) the dragon, establishing divine law among the lower orders of Creation. In Saint George and the Pterodactyl, we see an inverted mirroring of the legend.

Proportionally, the pterodactyl is huge—it’s as large as the horse and is a much more serious threat to George with it’s opening jaws and extended left claw, actually daring to do battle. The Heavens are absent, the Firmament omitted, and the earth visually overwhelms the viewer. Saint George’s halo is created by the mouth of a cave of columnar basalt (cited as Fingal’s Cave, Scotland) and the basalt continues underfoot leading the eye to the scene’s most surprising guest: a gargantuan sea octopus. George fights the pterodactyl with a short mace rather than a sword, and sports a truly spectacular handlebar mustache that even Nietzsche would have envied.

Hawkins’s works looked backwards to the Romantic era even as they anticipates the age of evolutionary science. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Triassic Life of Germany, Princeton University Art Museum

I like to think that Saint George and the Pterodactyl as a playful backwards nod to the era of American Romanticism in which Hawkins had come of age. His works, like those of the Romantics, exalted the wonders of nature and the explanatory value of traditional iconography. But Hawkins stands at the threshold between Romanticism and the age of Darwin. Instead of Heaven and the Firmament, we see a cave. Instead of a princess (Andromeda), we see a sea creature (the octopus). Instead of a mythical, cowering creature (the dragon), we see extinct animals (the pterodactyl) that have come to live to claim their own place in a narrative of natural history.

Saint George does not engage with his foe at lance’s length—he must be close to nature, however fraught with danger it is. An ancient iconography has become reimagined as an encounter between the man of science and his specimen. It marks the beginning of a new vision of humans in nature, expressed in the visual language of a world that was swiftly passing into history.

_01-large.jpg)