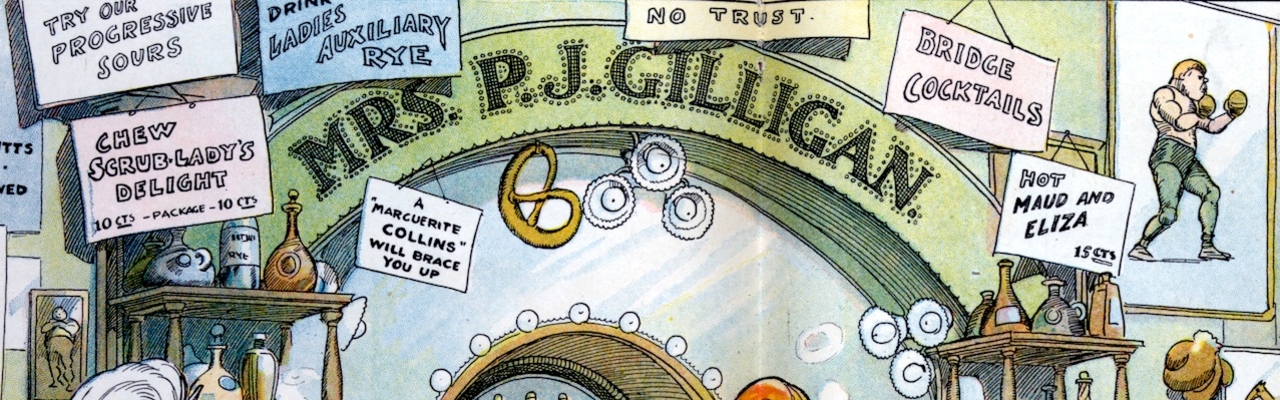

What exactly is going on at Mrs. P. G. Gilligan’s bar?

What exactly is going on at Mrs. P. G. Gilligan’s bar?

Smoking, Women’s Rights, and a Really Great Fake Bar: The Lady Smoking Caper of Ought Eight

Last year, a cartoon by illustrator Harry Grant Dart that appeared in the centerfold of the March 18th, 1908 issue of the political satire magazine Puck went viral.

It’s a scene set in a fictional New York bar called Cleopatra’s Cafe, Mrs. P.J. Gilligan proprietrix, which is populated entirely by women. Captioned “Why Not Go the Limit?,” it’s meant to be a gasp-worthy image of a hellish future in which widows play cards over the police blotter, mothers neglect their children and women assiduously follow news transmitted over a ticker that is not a stock ticker, by the way, but a sporting ticker reporting the results of horse races and boxing matches on which these degenerates have doubtless placed bets. It strikes a different note to many a modern viewer, however. Its charming cocktails (I’ll have a Hot Maud and Eliza, thank you), fashionably dressed, liberated Edwardian ladies and its free lunch banquet of almonds and fudge make it look like a pretty great place to hang out.

Harry Grant Dart, “Why Not Go the Limit?,” March 18th, 1908 issue of Puck magazine. Library of Congress

Editor’s note: You can now buy Dart’s image as a digitally-restored poster at our online store.

Most of the explanations of this image as it flew around the web saw it as an anti-suffrage piece, a vision of what could happen should the movement advocating for votes for women succeed. Benjamin Breen’s piece here on The Appendix, for instance, describes Dart’s illustration as “a parodic, misogynistic one that imagined a world where women could vote and, consequently, had taken the traditional place of men as drinking, smoking, gambling barflies.” The fact that every single woman in the scene is smoking comes up in an image caption as an ancillary issue, the result of an appalled fascination Dart harbored for women using tobacco products.

That’s actually the reverse of what is really going on at Cleopatra’s Cafe. Dart’s entire point was to lampoon women smoking in public, an issue that had exploded in the public conversation and was happening as he took pencil to paper, unlike women’s suffrage which was still a dozen years in the future. The subheading under the caption is “For the benefit of those ladies who ask the right to smoke in public.” That isn’t code for a wider campaign of women’s rights, like women demanding the right to smoke in public along with the right to vote. The suffrage movement had no interest in addressing the question of women smoking because it wasn’t a political issue but rather a debate over social mores and bore no relevance to the struggle for voting rights.

An 1890s caricature of a woman smoking while pursuing a coy man by illustrator C. E. Jensen, Copenhagen. Wikimedia Commons

Suffragettes were, in the main, society ladies – educated, moneyed, and importantly to them, respectable. The taboo against women smoking in public in turn of the century America associated the act with women of ill-repute (actresses, prostitutes, etc.), the kind of women who were distinctly not ladies or anyone a lady would wish to be around. Smoking telegraphed sexual availability, with co-ed smoking often described as “promiscuous.” In the mouth of a woman, it seemed, a cigar was not just a cigar.

This was not the case in Europe, where women smoking were a common sight by 1906 when New York Times correspondent Elizabeth Biddle reported from London how English ladies, even very proper young ladies who would never dream of going to a restaurant with a man without an appropriate married female chaperone, felt entirely free to light one up in front of everyone. When Biddle’s visitor from the US saw two “thoroughly respectable looking” women wearing no make-up and dowdy clothes (in contrast to slatternly actresses and other morally questionable women easily identifiable by their caked on the slap and vulgar, showy dresses) smoke in a restaurant, he begged her forgiveness for mistaking the restaurant for a reputable establishment and hustled her out the door.

The taboo was still strong in the United States, but would quickly weaken and collapse. What Dart’s cartoon is lampooning is a brouhaha that exploded in New York at the end of 1907 and the beginning of 1908 regarding the erosion of that taboo. It all started on December 29th when Jean (called James in English) Martin, owner of the luxury French restaurant Café Martin at 26th Street and Fifth Avenue, announced that ladies would be allowed to smoke anywhere in the restaurant on New Year’s Eve.

On New Year’s Eve all ladies who come to the Café Martin may smoke if they so desire. After this one night I may or I may not withdraw this privilege. Smoking by ladies is never objectionable. The smartest women in New York smoke, so why should puritanical proprietors rule against this mode of procedure any more than against the drinking of cocktails or highballs.

For a time our head waiters have been blind. They have not seen women smoking. But why not be honest? One thing I want to emphasize. I mean by this announcement that ladies may smoke. Some women who smoke are quite as offensive to the eye as when they drink. A lady smoking a cigarette is not so objectionable as another kind of woman drinking a cup of tea.

Note that class mechanism at work trying to extricate the act of smoking from its association with women, not ladies, of the demimonde. Rich ladies do it, ipso facto it’s not objectionable. Other restaurants like Rector’s quickly followed suit, and the shocking development made news all over the country. When New Year’s Eve came, reporters were on the ground to follow up on the pressing matter of which women were smoking and how much.

If all the women in the Café Martin had taken advantage of the proprietor’s permission to smoke if they wanted to on NYE, every one of the guests would have gone into 1908 in a haze so thick it could have been cut.

But the women, or a large majority of them, did not smoke. They seemed to have all sorts of a good time, but very few of them will have a chance to swear off the weed to-day. […]

There were perhaps a dozen women smoking the café at one time, a little before 12 o’clock. They did it modestly, for the most part, and it was very evident that many were beginners, taking advantage of the edict just for the fun of it.

Others appeared to be used to cigarettes and to enjoy them thoroughly. The smoking, however, was only a small part of the fun, for there was plenty to eat and to drink, songs to be sung, and jokes to be played, and every one was a good fellow, worth wishing a Happy New Year to.

So a few women (ladies?) smoked, the first ball dropped in Times Square and a good time was had by all. No biggie, right? Wrong. The backlash was swift and merciless. Within a week, a city ordinance was proposed prohibiting women from smoking in public places, public places in this case meaning establishments like restaurants, hotels, theaters, dance halls and what have you, not streets or parks. On January 21st, 1908, the New York City Board of Aldermen unanimously passed it. The Sullivan Ordinance, named after Tammany boss and the One Alderman to Rule Them All “Little Tim” Sullivan, enjoined all operators of such hostelries from allowing women to smoke on their premises. Violators would be sentenced to pay a fine of $5-$25 dollars and/or to serve up to 10 days in jail.

It is a mystery never fully explained why Little Tim, who himself owned several establishments of less than stellar repute in his homebase of the Bowery and whose cousin and partner in bossdom Big Tim Sullivan adulterously impregnated at least six actresses from his dance halls and would die of tertiary syphilis five years after the ordinance passed, suddenly found his monocle a’poppin’ over the very thought of ladies smoking in public. One possible explanation is that Little Tim saw it as a populist measure, a means to ensure fine uptown ladies didn’t get to smoke without opprobrium just like the not-so-fine downtown ladies in his purview didn’t get to.

Or perhaps his reasoning was more petty than that. Alderman Brown, who abstained from the voting, made sure the Times knew that he did “not believe the report that a certain well-known politician went to a restaurant some weeks ago, asked to have a table reserved, was told that all the tables were taken, and thereupon asked: ‘Do you know who I am?’ and on giving his name was told that it didn’t make any difference who he was, he could not have a table.” He absolutely did not believe that story one whit, and certainly not that said politician “told the proprietor of the restaurant that he would ‘hear from him’ or that this ordinance is the answer.”

Whatever the reason, the restaurants got the message. The Café Martin posted a sign on the front door informing women that the open smoking policy was rescinded. The previous policy of willful blindness went back into effect, with waiters looking the other way when respectable ladies accompanied by men had a little puff of their husbands’ cigarettes behind their fans.

The response to the ordinance was not entirely positive. Some women at the Gotham Club’s 1908 banjo and Chopin musicale protested vociferously against the practice of women smoking in public, but the men didn’t seem to be very riled up about it, and one of the women in secret admitted to a Times reporter that she actually did smoke but it wouldn’t do to approve of it publicly. A letter to the editor of the New York Times from an indignant woman called out Sullivan for his grandstanding and hypocrisy.

The anti-smoking law just passed affects a comparatively few women, but the principle underlying it is humiliating to every self-respecting woman, and is an insult to all.

Here we have a Bowery politician in his native atmosphere, the Bowery saloon and all it represents, vice in all forms unveiled, originating arbitrary laws for one-half of New York’s citizens, as if they were slaves or incompetents, without for one moment thinking it necessary to consult their wishes or opinions on the matter, just as if these citizens were not for the most part better educated, more moral, more law-abiding, and more self-respecting that the said Mr. Sullivan.

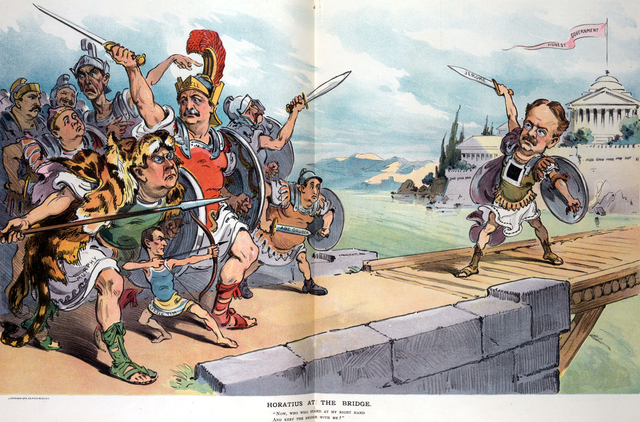

Iceburn! Such a monster iceburn. Because seriously, both Tim Sullivans were just drenched in corruption. So much so, in fact, that our old friend Puck magazine, which was of conservative Democratic leanings and was profoundly anti-Irish and anti-Tammany, in a 1905 centerfold placed them among the invading Tammany Hall politicans in the role of Lars Porsena’s army while a heroic William T. Jerome, District Attorney for the State of New York, stands alone as a valiant Horatius defending the bridge to “Honest Government.” (See Livy’s History of Rome, Book II, Chapter X for the story of Horatius’ solo defense of the Sublician Bridge in the face of Etruscan invaders.)

Even the Times, whose editorial page was far from in favor of women smoking, thought it was as ridiculous as when Peter Stuyvesant tried to force women to wear only “broad flounces” (apparently a type of petticoat ruffle in this context, although broad flounces were part of women’s dresses as well) and only dance “shuffle and turn” steps. The prohibition alone, went the logic, could be sufficient to cause women to rebel and smoke like chimneys where previously they had not.

Then there was an arrest. On January 23rd, 1908, at 1:20 AM, one Katie Mulcahey was witnessed by a beat cop striking a match against a house on Bowery and Division Street and lighting a cigarette. She was taken to night court where she refused to give her address and told the judge she’d never heard of the law and wouldn’t care if she had. She was fined $5 which she did not have and so was taken to jail.

This absurd bungle was a function of all the chatter about the ordinance, because it didn’t actually follow the law itself. The ordinance did not prohibit smoking on the street and held the owners of establishments culpable for women smoking, not the women themselves. The misapplied and misbegotten regulation didn’t have long to live anyway. On February 2nd, while Little Tim Sullivan was in Hot Springs, Virginia, trying to treat the kidney disease that would kill him in a year, Mayor of New York George B. McClellan, Jr., son of the Civil War general of the same name, vetoed the ordinance as illegal.

A month later, Puck grumpily published Harry Grant Dart’s vision of a bar full of ladies smoking, gambling and eating fudge. This is what it’ll come to, is the message, if you allow these ladies to indulge publicly in the vice of tobacco. They would all soon get a chance to find out. Within a few years, establishments allowing women to smoke were the norm. In 1911, Andre Bustanoby, co-owner with his brother Jacques of the elegant Café des Beaux Arts, put it succinctly:

“We think our clientele know better than we do what is proper and what is not. They are adults. They have traveled all over the world. We give all liberty to those coming here and none of them has ever taken advantage of us. They have as much common sense as we have. We do not see we have any right to ask one of our friends to stop smoking if she thinks she ought to smoke. A law against smoking in public by women would be a foolish law.”

This post was reprinted with permission of the author from The History Blog, a site that every Appendix reader should check out immediately.