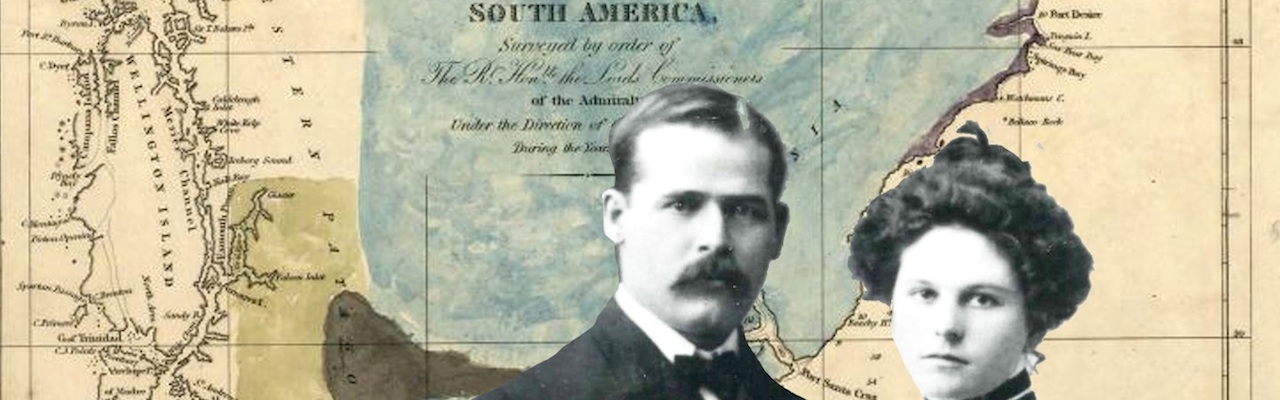

Digging for traces of legendary outlaws in Patagonia (pictured here: Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, aka the Sundance Kid, and Ethel Place in 1901.)

Digging for traces of legendary outlaws in Patagonia (pictured here: Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, aka the Sundance Kid, and Ethel Place in 1901.)

Spelunking the “Murk of Outlaw History”

Like most people, I knew nothing of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid apart from what I’d remembered from the 1969 movie: two wisecracking bandits went off to Bolivia and got themselves shot. Oh, and a girl tagged along but left before the bullets flew.

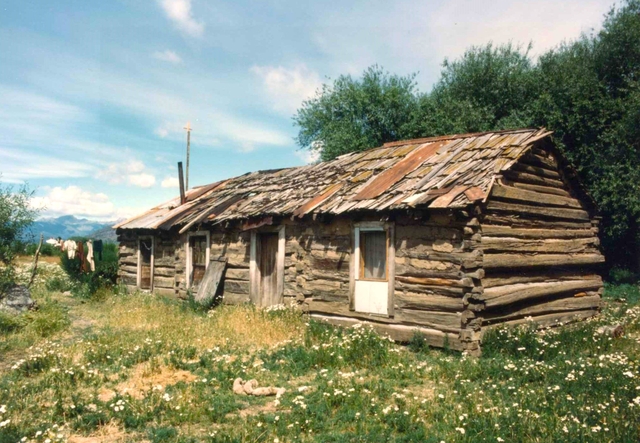

In 1985, while prepping for a trip to Patagonia, my wife Anne Meadows and I read that the trio had actually first settled there, homesteading a small ranch in Chubut for several years before being chased out by the authorities. We stopped by their old cabin in the Cholila Valley one December afternoon and visited with its sole occupant, Aladín Sepúlveda, a grizzled, stoved-up gaucho whose father had taken a lease on the property not many years after the bandits had fled. Born there in the early 1920s, Sepúlveda had lived in the cabin his entire life. He was more than a little fuzzy about the bandits, though he did repeat several times that he was one of 15 brothers and sisters. We interviewed a few neighbors, who added some anecdotes, and thought that we might write an article about the Wild Bunch trio in Cholila.

Upon returning to the United States, we checked in with a few Old West researchers and soon learned that a controversy simmered about what had become of Butch and Sundance. Did they die in Bolivia or elsewhere? All in all, there were more than 60 accounts of their deaths in South and North America, not to mention Europe (Butch had been stabbed to death in a Paris alley), from the late 1890s to the mid-1970s. Several people claimed, or others claimed for them, that they had survived the Bolivian shootout and returned to the Rockies safe, sound, and well tanned.

Welcome to, as Bruce Chatwin once put it, “ the murk of outlaw history.” Chatwin had been in Chubut a decade before us, fell head over heels for the Butch and Sundance saga, and featured it in his classic travelogue, In Patagonia.

The article we planned morphed into many, and Anne wrote a book, Digging Up Butch and Sundance, recounting our adventures chasing Butch and Sundance’s vapors. The digging of the title refers both to quarrying archives and, in an ironic sense, the excavation of a grave in Bolivia that turned out to contain the remains of a German miner named Gustav Zimmer. No one is ever buried where they’re supposed to be, we learned. Untangling the mystery of the bandits’ fate proved to be a more a matter of weighing untidy accumulations of evidence. The evidence supporting the idea that they died in Bolivia is better than the evidence supporting some other scenario. One cannot get out of a field of study, in this case, “the murk of outlaw history,” more than the rules of that field allow.

You can read more in my Appendix article “Bandit Resurrections: Who Was the Real Sundance Kid?,” and in the books linked to below.