Inside an Edwardian paleoanthropological hoax that remains shrouded in mystery.

Inside an Edwardian paleoanthropological hoax that remains shrouded in mystery.

Piltdown Man: Untangling One of the Most Infamous Hoaxes in Scientific History

Few scientific forgeries have captured the scientific and public imaginations as completely as that of the 1912 Piltdown Man hoax. While examples of blatant fraud can be found in many scientific disciplines over the centuries, out-and-out forgeries and hoaxes prove to be relatively rare. The Piltdown Man is one of the most studied and least resolved incidents in the history of paleoanthropology—an episode surrounded by mystery and intrigue.

It would seem that just about everyone who is anyone in the paleo-community of the last sixty years has a theory about who perpetrated the fossil hoax; why it lasted as long as it did (forty years); and what Piltdown meant (and means) to paleoanthropology. Suspects charged with perpetrating the hoax have included the fossil’s discoverer Charles Dawson, scientific notables like William J. Sollas and Sir Arthur Keith, and even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

-medium.jpg)

A 1915 group portrait by John Cooke, Charles Dawson and others associated with the Piltdown find. Wikimedia Commons

In the first decade of twentieth-century, the fledgling discipline had few fossils to hang its science on. A couple of Neanderthal skulls, a few specimens from France, some scattered skeletal elements from around Europe, a skull from Australia—to say nothing of Eugene Dubois’s famous 1891 find in Java (which he termed Pithecanthropus erectus) which firmly established Southeast Asia as an epicenter of human evolution for the scientific communities of Europe. Equally as debated as the geographic origin of human ancestry was the evolutionary sequence of “human-like” traits and the order that these traits appear in the fossil record. For the early twentieth-century paleo-community, the question of whether brains (read: a surrogate for culture) developed before or after bipedalism (read: non-cultural anatomy) occupied a good proportion of paleo-research efforts.

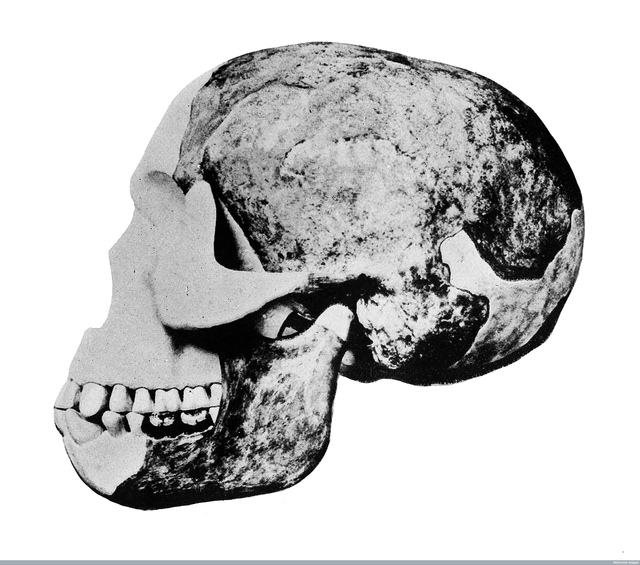

The Piltdown material itself came to the attention of British intellectuals, like paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward, via the British Museum upon the fossil’s excavation in 1912. The Piltdown fossil consisted of a mandibular fragment (the lower jaw) as well as portions of the crania (the skull), recovered from the Piltdown gravels of East Sussex by antiquarian Charles Dawson. The find was promptly and rather grandiosely named Eoanthropus dawsoni.

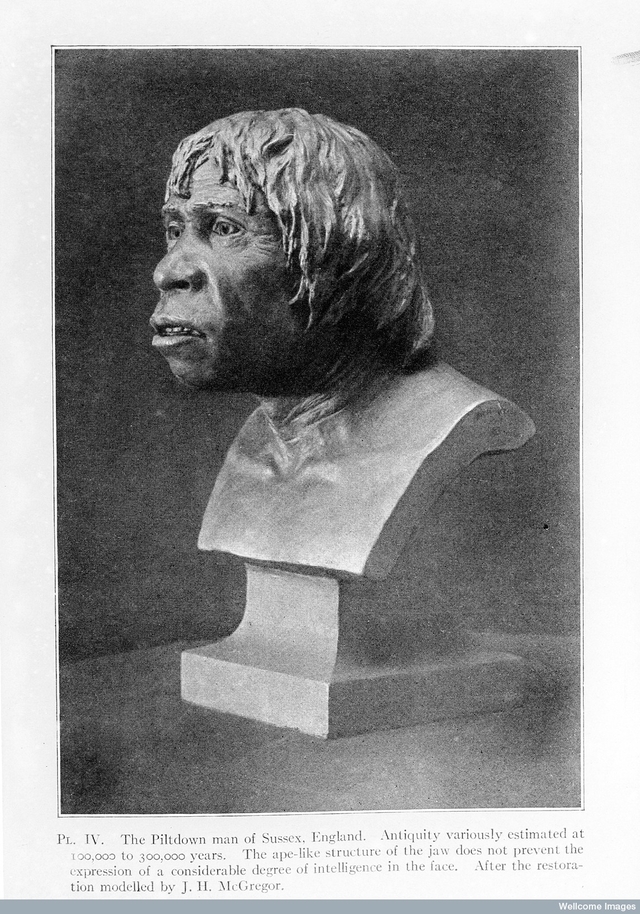

Woodward claimed that the find pointed to a “missing link” in the chain of human evolution—a fossil that could be reconstructed as a human ancestor with a large brain. This would have been a testament to the long-term significance of culture and intellectual prowess in the evolution of Homo sapiens.

Woodward wasn’t alone in his interpretation. The Piltdown fossils became readily accepted by the paleo-community. Indeed, many fossils found in subsequent decades (such as the 1925 Taung Child in South Africa) were ignored due to the influence of Piltdown. Even prominent American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn (then-president of the American Museum of Natural History) declared the skull and jaw a perfect fit and the specimen fascinating.

A photograph by John Frisby of Uckfield, showing excavations at the Piltdown gravels in 1912. Standing centre left in the picture is the white-bearded figure of Arthur Smith Woodward and working in the trench on the right is Charles Dawson, the local solicitor who had “discovered” the skull of “Piltdown Man.” Photo and caption courtesy of photohistory-sussex.co.uk

Arthur Smith Woodward and Uckfield photographer John Frisby inspect the excavations at Piltdown in 1912. Arthur Smith Woodward was a palaeontologist and Keeper of Geology at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. photohistory-sussex.co.uk

In 1953, a committee of sorts convened to evaluate the growing dissatisfaction with the fossil and the evidence against it being legitimate. In the end, “fossil” was demonstrated to comprise three “modern” species—a human skull, an orangutan jaw, and chimpanzee teeth. The teeth had been filed down and the entire set of bones stained with an iron solution. A few scientists in the early days of the fossil’s fame (like Franz Weidenreich, discoverer of the 1930s fossils ascribed to the so-called Peking Man) declared the fossil a forgery, but it wasn’t until 40 years after the fossil’s entry into the paleo community that is was exposed for what it was.

But what was it? A forgery? A hoax? A joke? A gross error in bending facts to fit a theory?

On some level, the Piltdown “fossil” is all of these things. However, it is also an important lesson not only about early twentieth-century science’s search for a missing link, but also our own. In a discourse where chains, links, and linearity are treated not only as helpful metaphors (“the Great Chain of Being,” “the Tree of Life”), but as actual explanation for biological phenomenon, Piltdown Man serves as a reminder that missing links can also be invented ones.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to acknowledge the Pennoni Honors College, Drexel University and the generous time and conversations of Dr. Francis Thackery (University of Witwatersrand.)