Inside the imagined futures of Cold War annihilation.

Inside the imagined futures of Cold War annihilation.

How to Hide a Nuclear Missile

After its Cuban Missile Crisis experience, Kremlin leaders wanted to ensure the USSR would never again be outgunned: one might call it ‘Cuban Missile Syndrome.’ The result were new missile systems, including schemes to cache nuclear warheads in the deep ocean and outer space. But before the strange logic of nuclear warfare could move off-world—and partially because the very effort placed too much strain on its economy—the Soviet Union collapsed. What follows is a history of these imagined futures of Cold War annihilation.

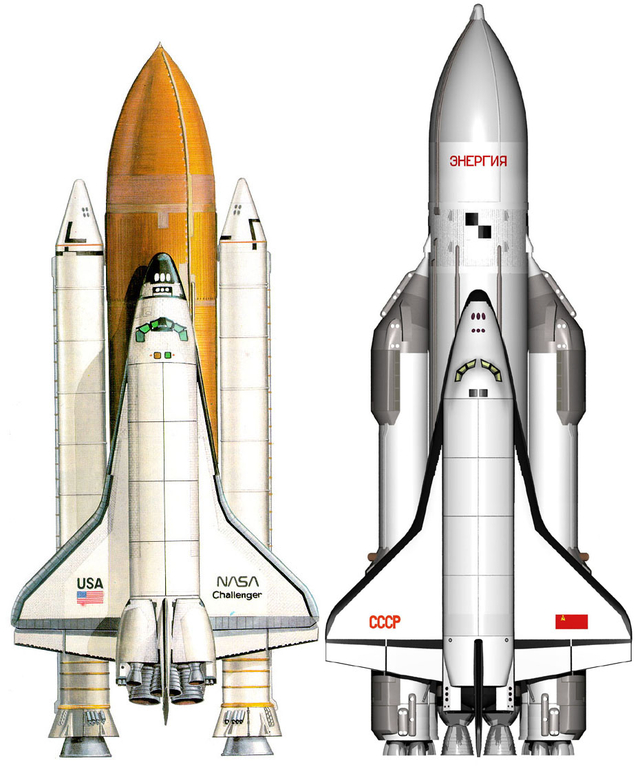

Throughout the 1970s, the Soviets launched a number of intimidating new weapons systems, from the SS-18 Satan missile to the Kiev, the Soviet Navy’s first aircraft carrier. Meanwhile, the Soviet Air Force launched the Tu-22M ’Backfire’ strategic bomber, which could deliver nuclear weapons over long distances. By 1974, meanwhile, Soviet engineers were working on a reusable spacecraft prototype that could be used to easily launch spy satellites—a program that resulted in the Buran craft, otherwise known as the Soviet space shuttle.

NASA’s space shuttle compared with its strikingly similar Soviet counterpart, the Buran. Both were the product of a heated technological race between the two superpowers in the 1970s and ’80s. Wikimedia Commons

Many US defense analysts wondered what the Soviet Union was up to here. Was this an effort to achieve a military victory in the Cold War?

We now know that the Soviet Union were building massive missiles and rockets for a simple reason: they were good at it. It was their area of comparative advantage.

American missiles were smaller because their guidance systems were more sophisticated, ensuring greater accuracy and requiring a smaller warhead to hit the designated target area. Soviet missiles needed to be bigger so they were guaranteed to hit their target, and building big rockets with big warheads was something Soviet weapons designers could do well.

At the time, however, this was unclear to American defense analysts. To some of them it seemed that the Soviets were developing ‘silo busting’ missiles.

A number of those concerned about Soviet deployments joined the Committee on the Present Danger (CPD), a group dedicated to voicing concern about the survivability of the US nuclear force. These new Soviet missiles could potentially destroy US missiles in their silos in a devastating first strike, and thus win the cold war.

How so?

In this scenario, CPD analysts reasoned, the submarine leg of the nuclear triad was useless, because seaborne nuclear warheads were not big or accurate enough for any mission other than ‘city busting’. But ‘city busting’ was a terrible option: would a president order a retaliatory strike on Soviet cities knowing that to do so would invite the destruction of American cities? (The ‘Second Strike’ problem).

Dr. Strangelove pondering second strike options in Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film of the same name. Wikimedia Commons

This conundrum encouraged new, imaginative thinking on how to ensure that American nuclear missile would survive a surprise Soviet attack.

In 1981, a number of Committee on the Present Danger members participated on an ‘MX Missile Basing Advisory Panel’ and wrote a detailed report 3 on how to better ensure the survival of American nuclear missiles.

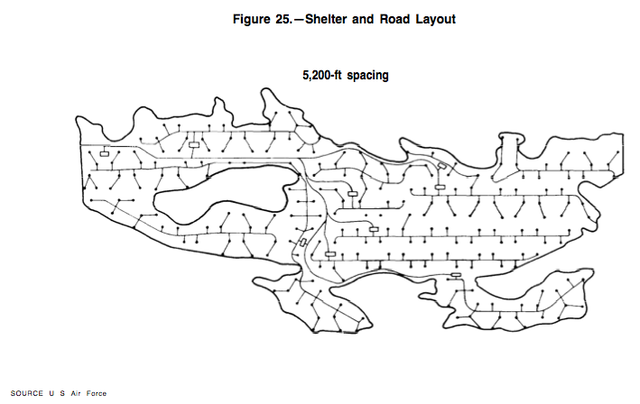

In the report, the basing option that received the most attention was the ‘Multiple Protective Shelter (MPS)’ option. A new generation of American missiles, the MX missile, would move on road tracks between a number of silos. This would increase the number of targets for Soviet warheads, as Kremlin military planners would not know which silo a missile was in at any given moment. They would be forced to target them all, which would reduce the Soviet advantage in missile numbers.

There were also more extravagant suggestions, including a ’Small Submarine’ option. Four missiles would be housed in numerous diesel powered mini-subs, operating within 1000 miles of the continental United States. A new submarine fleet, the report conceded, was ‘a major undertaking’ and wouldn’t enter service until at least 1992-94: too far away. The program never got started.

Incidentally, the report might have mentioned ‘Project Sunrise’; a prototype system from the 1960s that envisaged missiles based on the seafloor. Now there’s a morbid name for a missile system.

Another particularly fantastic solution was the ‘Deep Underground’ option. The idea was to bury a missile deep inside a mountain, entirely sealed off from the outside world. Affixed to the top of the missile would be a ‘tunnel boring machine’ that would drill through the mountainside to reach a launch position. Sheltered by the mountain, the missile could survive a surprise attack and be ready for a retaliatory strike.

Unsurprisingly the costs of developing this ‘mole missile’ were enormous—or, more accurately, cost estimates were reported as being ’highly tentative’—and the design never left the drawing board.

Aside from cost, a problem with all these solutions was verification.

Arms control agreements rested on the ability of each side to check whether the other was cheating. Hiding missiles in mountains or in undersea platforms would have made verification impossible.

The ‘race track’ option lived on for several years because it did permit verification: at an agreed time, all the silos could be opened for Soviet satellites to check there weren’t more than the permitted number of missiles. (This was surely the best time for a surprise attack.)

Ultimately an even grander solution was devised: Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars program (the Strategic Defense Initiative). Rather than hiding or protecting American missiles to ensure a force capable of answering a surprise Soviet attack, a space-based platform would shoot down incoming missiles.

Of course, typical cold war paranoia ensured that some American analysts assumed the Soviets were well ahead in their own version of the Star Wars program.

An earlier version of this post originally appeared at Nick Blackbourn’s research blog.