This distinctive brand of apocalyptic and anti-government belief has long figured as a powerful counter-current to the utopianism of American culture.

This distinctive brand of apocalyptic and anti-government belief has long figured as a powerful counter-current to the utopianism of American culture.

Technology and Apocalypse in America

In April of 2014, televangelist Pat Robertson devoted a segment of his 700 Club TV program to discussing what he ominously termed the “biblical implications” of radio-frequency identification, or RFID. In the tech world, RFID rather mundanely refers to technology that allows information to be stored and transferred on radio-sensitive tags at a distance of at most a few feet, aiding in commercial micro-transactions and other smartphone-enabled conveniences of modern life.

As Robertson and his guest, author and biblically-oriented “privacy expert” Katherine Albrecht explain, matters on Earth are never merely as reported. For them, new developments in the world of techno-commerce align in troubling parallel with the Book of Revelation. RFID is nothing less than a strong candidate for the Mark of the Beast. According to chapter thirteen of John of Patmos’s book, this 666, “the number of his name,” shall be inscribed upon the bodies of “small and great, rich and poor, free and bond” so that none may buy or sell without such a mark. The mark divides the sinners from the Christians who will refuse branding and suffer persecution and martyrdom in the Last Days.

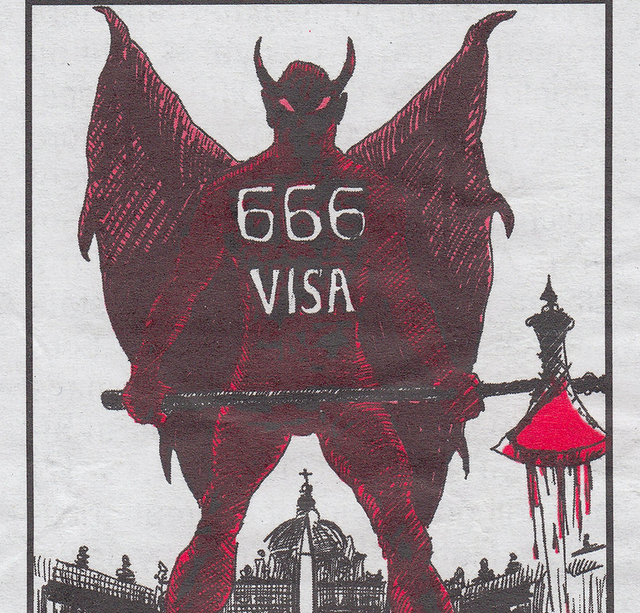

RFID is, of course, not the first novelty to be singled out as the Mark of the Beast. A famous image from the fierce vernacular art of twentieth-century American biblical tracts shows a Satan-figure, rising above Saint Peter’s Square and a multitude of human corpses, clutching an executioner’s axe. The words “666 VISA” are emblazoned on his broad chest. Radio-frequency identification technology thus merely figures as the latest supposed harbinger of the end times in a culture obsessed with both the apocalypse and technology. “We’re going into some strange worlds ahead of us, ladies and gentlemen,” Robertson warns. He’s not wrong.

These anxieties about the entanglements of human life and technology, of the movements of the body mapped onto the geographies of power, have a deep pedigree in Judeo-Christian thought. Biblical scholar Robert Alter notes that, as early as Exodus 30:12, when a census of Moses’s people comes bundled with a “ransom” of a half shekel in symbolic exchange for the counted’s life, there has been “a folkloric horror of being counted as a condition of vulnerability to malignant forces.’” Beginning in the Davidic narrative of the Book of Samuel, Israel’s most famous monarch chooses to count his subjects, with disastrous results. Mapping and counting, in these stories, acts as a sort of dowsing rod, auguring the collision course between the profane world and the divine. This is only cast in deeper relief by the long obsession America has had with its own teleological importance. Puritan ideologues sought to establish their utopian City on the Hill. In the post-Revolutionary years, influential preachers such as David Tappan and Timothy Dwight, of Harvard and Yale respectively, proclaimed the young republic’s providential role in world history, laying the groundwork for the Second Great Awakening.

Prognostications of doom abounded in nineteenth-century and twentieth-century American folk cultures. In his work on popular eschatological beliefs in early twentieth-century Ohio, folklorist Newbell Niles Puckett recorded “cows lowing at night, bad thunderstorms” and the sudden fashion of women wearing “glass high heels” as a sure indication that the end times had arrived. This very twentieth-century image, which seems to mingle the quiet surrealism of advertising displays with the cryptic visions of the Revelator, combines consumerism and apocalypticism in a disquieting manner. An undercurrent of anti-government thought has long informed this particularly American brand of eschatological belief.

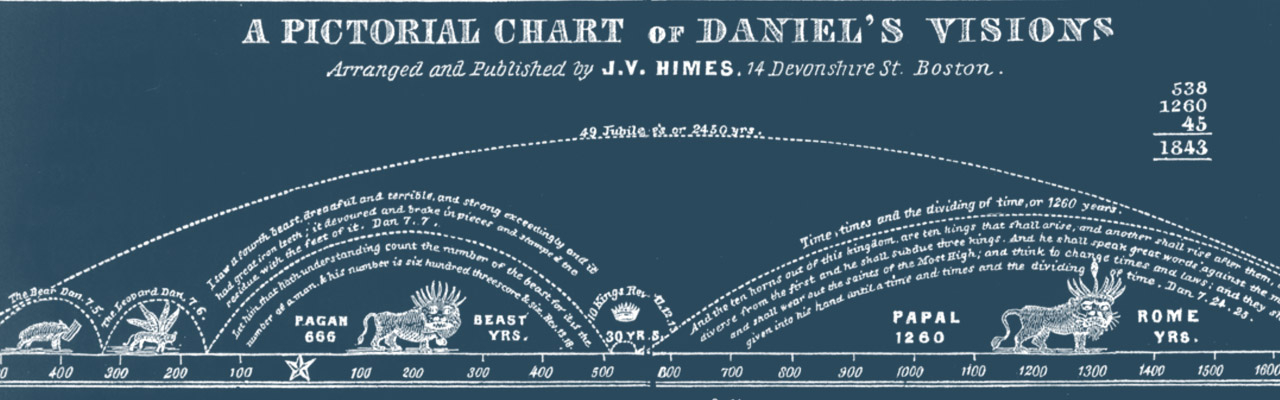

Millerite prophetic chart from 1843, from P. Gerard Damsteegt, Foundations of the Seventh-day Adventist Message and Mission (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1977), 310.

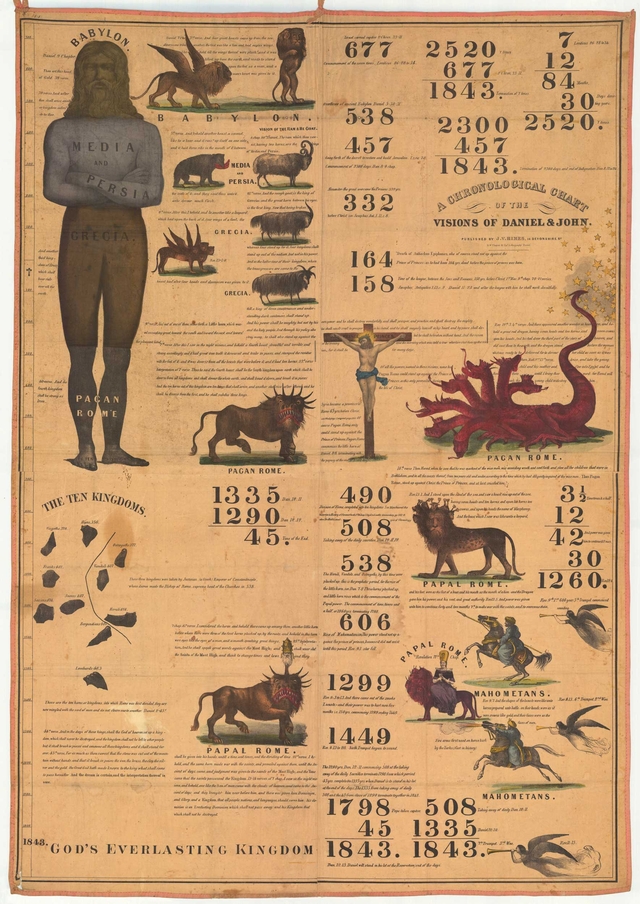

Groups like the Millerites, who weathered numerous unfulfilled prophecies and subsequent schisms in the nineteenth century, exemplified this strain of American apocalypticism. From the very beginning, William Miller and his followers identified the United States as a potential enemy, drawing on “the apocalyptic visions of the biblical books of Daniel and Revelation, where he saw governments portrayed as wild beasts which hurt God’s people.” Miller reversed America’s eschatological significance as the City on a Hill, positioning the appearance of the republic on the world stage not as a positive harbinger of a golden age, but as a dark force pointing towards a coming cataclysm.

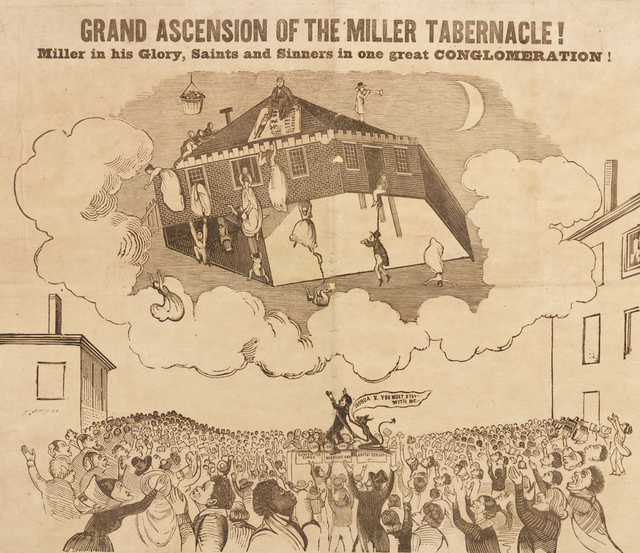

A broadside depicting the chaos of the end of the world, 1844, via the New York State Historical Society.

In the fallout from the Great Disappointment (when Miller’s predicted apocalypse on October 22, 1844, utterly failed to arrive) the Millerites fractured. One off-shoot would become the Seventh-Day Adventists, who believed in a looming worldwide conflict centered on the correct observance of the Sabbath and who denied the government’s right to conscript them to military service.

Today, the message boards of conspiracy websites and the world of shortwave radio resound with conspiracies about the deadly significance of gun-owner registries, FEMA camps, government-run healthcare, national ID cards, or any other form of centralized data-collection. As the anthropologist Susan Lepselter writes in her work on UFO-oriented conspiracy buffs, “just as the power of the state tries to usurp the power of God, the power of a monarchlike, computerized system usurps the power of democracy.”

This distinctive brand of apocalyptic and anti-government belief has long been a powerful American counter-culture. Contemporary public debates about privacy, government intrusion, and the limits of state security dip into these wells, often without knowing it.