Journalist Chris A. Smith searches for “the Mick Jagger of Zambia.”

Journalist Chris A. Smith searches for “the Mick Jagger of Zambia.”

Searching for Jagari

In 2010, my friend Nick and I traveled to Zambia looking for lost rock stars. It felt like a long shot. The country’s once-vibrant 1970s rock scene was long dead, the victim of economic collapse, geopolitical strife, and the AIDS epidemic. Most of the musicians were dead, too, many from AIDS. We knew, however, that the biggest name in Zambian rock ‘n’ roll, Emmanuel “Jagari” Chanda—Zambia’s Mick Jagger—was still alive. We just didn’t know where he was.

The search began in Lusaka, the easygoing, slightly ramshackle capital. We checked into a cheap government-run hotel, which was attached to a casino frequented by Chinese businessmen. After a small army of friendly desk clerks copied our passport details onto carbon-paper forms, we set out to follow our best lead.

Our first stroke of luck was Nick’s nationality. Simply by virtue of being English, it seems, my friend had a few key connections to this former colony. We caught a cab to the Polo Grill, a colonial relic popular with the local elite, to meet a guy who had gone to school with Nick’s sister in London. This man’s father, a reformist government minister, had been murdered in a home invasion in 1998. The robbers didn’t steal anything. Many say it was a political assassination.

The information emerged in dribs and drabs; our new friend had a cryptic manner. But he said he knew one of Jagari’s sons. We toasted our good fortune, looking out over the freshly mown polo field, wondering if it could possibly be so simple.

Jagari’s son Dale was waiting in the hotel lobby the next morning. He told us Jagari was tending to his gemstone mine on the Congo border—a world away over bad roads. Spreading a map across a patio table, we hatched a workaround: We’d drive north to the Copperbelt city of Kitwe, Jagari’s hometown, and he would catch a minibus across the southern tip of Congo to meet us. If all went well, we’d be hanging out with him by dinnertime the next day.

Kitwe, the center of Zambia’s industrial heartland, had a lush, sinister air, all pitted roads and leafy, overhanging trees. En route to our guesthouse we stumbled into a political rally that had just broken up. The crowd was riled up, probably drunk, and spilling out into the street. We couldn’t turn around, so we drove slowly through the crowd, the sea of men parting reluctantly at our passage. One man walked alongside my window. He cocked his hand into a pretend pistol and aimed it at my head. With a smile, he pulled the trigger.

A few hours later we met Jagari. He held court for the next three hours over rump steak and Coca-Cola, an Internet rumor made flesh. We had been in the country less than 72 hours, and we had found our man. It had been laughably easy.

So we began to think bigger. Maybe we could make a film—another Buena Vista Social Club, another Searching for Sugar Man. To make a documentary, though, we needed film of Jagari and his band, the Witch, from the 1970s.

Jagari didn’t have any footage, but he thought some must exist. He recommended we look up Billie Nyati at the Zambia Music Parlour, home to dozens of Zambian bands over the years. The label’s founder was dead but Nyati was still around, winding up operations at company headquarters in Ndola, another Copperbelt city. Jagari didn’t have Nyati’s number, so he gave us directions: It’s near a filling station at the junction with the downtown post office.

Armed with those rather vague coordinates, we spent a half-day asking around. When we found Nyati, he was dressed in a hip-looking safari suit and a baseball cap emblazoned with a dollar sign—pretty close, actually, to my fanciful idea of what a Zamrock record magnate might look like. He didn’t have any footage, but he graciously showed us a backroom stacked with piles of old reel-to-reel recordings of Zamrock, disco, Congolese, and kalindula music. Nyati seemed nonplussed by the mess. “I must organize it,” he said.

The quest continued back in Lusaka. Searches at The Times and The Post came up empty; same with DB Studios, where a host of famous Zambian albums were recorded. We asked the media impresario Errol Hickey. No luck.

Everyone, though, pointed us to ZNBC, the state broadcaster, which documented everything during the first few decades of the country’s existence. People told us there had been a devastating fire there at one point. We wondered, too, if the state archives were any better maintained than the Music Parlour’s—the 1970s were turbulent years, and funding was scarce. Still, if anyone had footage it would be ZNBC.

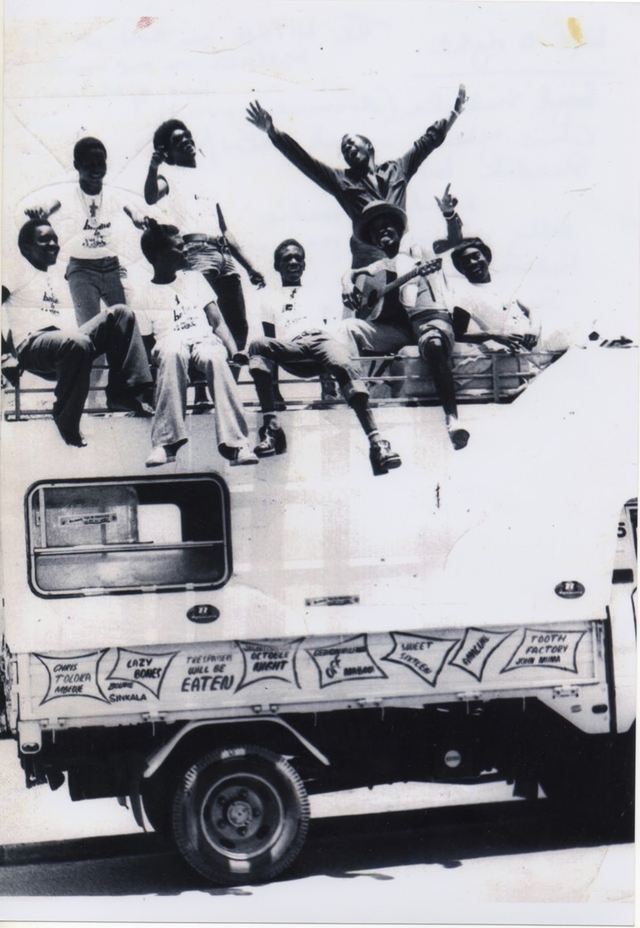

The Witch’s touring van (seen here in Malawi, in 1975) became famous in its own right. The Lusaka music journalist Felix Nyambe remembers, “If you saw that van, you knew the Witch was in town.” Psychedelic Baby Blog / Jagari Chanda

We had to leave Zambia before we could find out. I deputized an A/V entrepreneur I had met at Radio Phoenix to continue the search. As the months passed, Theo’s initially hopeful emails grew pessimistic. Finally, in March 2011, he conceded defeat. “They seem not sure of what they are doing or just telling us stories,” he wrote. “Looks like they don’t have the footage coz it’s been weeks now they are not coming up with anything.” He signed off: “Sorry sir I tried be blessed.”

That particular dream was dead. (At least for us. There are now two Zamrock documentaries. One doesn’t use old footage; the other isn’t out yet. Maybe those filmmakers dug up what we couldn’t.)

Then again, we had found more than we dared hope. I thought of our encounter with a worker at the government hotel after we met with Dale. We were in the lobby, lingering over breakfast. “Not to be nosy,” the worker said. “But I saw your map. Are you here in search of gems?” Nick and I looked at each other. The large copper mines were owned by foreign companies, but mining was off-limits to individual foreigners. Was this guy going to report us? Or did he want in?

I told him the truth. It must have sounded absurd, because his face clouded for a moment. Then he smiled politely and walked off. He didn’t believe me for a second.