Isle of the Dead, 3rd Version, Arnold Boecklin, 1883.

Isle of the Dead, 3rd Version, Arnold Boecklin, 1883.

The Studs Terkel Effect Pt. 2: When Experimental History Is Personal History

It’s the summer after I graduated college, 2003, and my father gives me a reprint of a lecture by his mentor in anthropology, Lambros: “With Ithaca on My Mind.” I don’t read it, though it’s easy to pretend that I have. Visits to Lambros’s office have gone from embarrassing to a pleasure. I used to read comics to avoid talking to the smart and beautiful graduate students that popped in to say hello. Now I sit and listen, sip Lambros’s rum, take in his stories of World War II, and field work in the Caribbean and South America. I know it all already, I think, and I tuck “With Ithaca on My Mind” in a box that trails me in my new life as a journalist.

As a phrase, ‘oral history’ has been around for a while, with striking continuity of meaning. “I have been amazed by observing in my own local researches, the ravages made by a single decade, among the fountains of oral history in a community,” lamented one Vermont local historian in 1863. Its first institutionalization, however, initially had a stricter idea of whose spoken account of the past mattered: national leaders, mostly men. Absent were the sort of lives recorded by ethnologists in the late 19th century, by interviewers under the Federal Writers’ Project of the 1930s, or that “Professor Sea Gull,” Joe Gould, claimed to capture in New York during that same era. (Further down the rabbit hole: Joe Gould might have called his mostly mythical magnum opus the Oral History of the Contemporary World, but it was as much about himself as anyone else. For his amazing story and its echoes, see Joseph Mitchell’s Joe Gould’s Secret, and Mitchell’s own slice-of-life accounts of New York.)

What Studs Terkel did to ‘oral history’ was popularize it. Born Louis Terkel in New York City in 1912, he was employed by the WPA in the 1930s and was an on-air radio professional through 1997. Most importantly, Studs explored U.S. history using the words of its people. Starting with Division Street: America in 1967, and continuing with 1970’s Hard Times, and 1984’s The Good War, Studs staked out a big-hearted Whitman-esque (better: Carl Sandburg-esque) patch of ground, winning plaudits from critics and the marketplace while forwarding a not-so-subtle moral standpoint (The Good War won the Pulitzer Prize while laying out why World War II was not that good.)

But here’s the thing: despite his gingham checked shirts, and homespun rhythm, Studs Terkel’s populism was deeply, radically experimental. The interviews that appeared in his books weren’t transcripts—they were curated narratives. We do not speak in full, complete thoughts and paragraphs. He gently shaped and edited the narrative of his interviewees to create first person through-lines that still reflected their idiosyncratic take on which history mattered, what made them laugh and weep, and what they wanted in their lives.

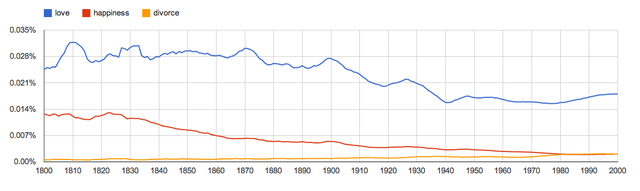

This is a radical power, turned to a popular end. Narrative history, a cousin of oral history, I’d argue, can thus be a hundred times more complex and meaningful a technology than Ngram, the Google search engine that lets you trace (published) word use (in books that Google has scanned) over time. To re-jigger my co-editor Ben’s experiment: I enter case-senstive, comma-separated ‘happiness, divorce’ into the Ngram Viewer and get a long decay and a mild rise. I add ‘love’ and see something else:

Image courtesy of Google Ngrams

This is vaguely comforting, and, as Ben pointed out in his original post, I can project onto it all I want. But to go in the other direction—taking people’s stories—whether oral, written, or gathered from a thousand census reports—and shaping them into a larger narrative aggregate will tell us more about the subjective experience of living history than how many more people talked about love in 2000, versus 1980. It will tell us about ourselves.

It is 2005, and I am an interview facilitator for StoryCorps, the new York-based oral history program inspired by the WPA and Studs Terkel. It is the best job I will ever have, though I will leave it too soon. I record a Sri Lankan couple singing about a lost fisherman after the 2004 tsunami, laugh with bohemian aunts, struggle through overwhelming interviews with 9-11 survivors, and fall in love three times weekly. Today is different. I’m waiting at the recording booth in Grand Central Station for my father, who is going to interview Lambros, his mentor. They arrive flustered, thrown by navigating midtown traffic, and I am anxious and fail to set them at ease. Lambros’s stories are great, as always, but I’m off. I am prompting Lambros too much, silencing my dad. I am trying to control the narrative by removing my father from it. I am trying to make it be about Lambros’s funny stories when perhaps what it should be about, what I’m maybe afraid of it being, is why three men of three generations are sitting in a soundproof box underground and one of them is not my grandfather.

Happily, I know I’m preaching to the choir. There are established academic historians out there who are playing with narrative form, using the techniques of fiction and screen to craft well-documented histories as thrilling as any novel. There’s a young generation of historians coming up who are interested in nurturing the writerly and subjective part of their craft. “We’re talking about how form and content are necessarily intertwined,” one fellow PhD candidate (and contributing editor for issue 2 of The Appendix), Amy Kohout, recently told me. Kohout’s a member of “Historians Are Writers!” at Cornell, a group meets monthly to discuss the writing of history and holds a History Slam each spring. (For pieces from one recent slam, see this terrific issue of Rethinking History, another fantastic venue for the ideas I’m grappling with here). Expect to see pieces from them in The Appendix soon.

In the meantime, The Appendix will be engaging in its own kind of narrative play. Our first issue includes some histories of a more recognizable shape—a murder trial in 18th century Sierra Leone, Pentecostalism and the Guatemala Maya—but others will be comics, poetry and historical fiction. Others embrace the first-person experience of being shaken up personally by an archival find, or narrate a history from not one but two authorial voices. Our hope is that by not only giving space to the strangeness of history, but the strangeness of narrative itself, we can write histories that bring more people aboard, and sail us farther than we imagined.

It’s the summer of 2012. I have come and gone from StoryCorps, and begun an academic career of my own, studying the history of anthropology in the Americas as a discipline—why individuals from one country collect the stories and bones of the living and dead from another. My wife and I are packing for a year in South America. From a forgotten box I pull Lambros’s “With Ithaca on My Mind,” and I absently tuck it into my backpack. I finally read it on the plane and learn more about Lambros’s work than I ever knew: stories of Jamaican fishermen and rural Bolivia, interviews with Greek hashish users forcibly ‘repatriated’ from Turkey more evocative than fiction: “… There we were in the stinking port of Pirawus. The sound of thievery echoed there, there were card sharks, pickpockets, lottery sellers, hashish users and others, manges and criminals and koutsavakia.”

Still, though Lambros mentions that his mother and father were born on the Greek island of Ithaca at the lecture’s beginning—a fact that probably everyone in the audience knew—and ties them to Kavafy’s poem, Ithaca, he speaks little of himself, concerning himself with cultural and social innovation, research, and service. I look at the reprint’s cover, wondering why my father gave it to me, and I see the date, 1989. I think of my father moving out, migrating back to New York, his children cycling through on weekends. I think of parents and grandparents. The family we have, and the family we make. The history we have and the history we make: </p>

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you would not have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you will have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

- C. P. Cavafy, "Ithaka"