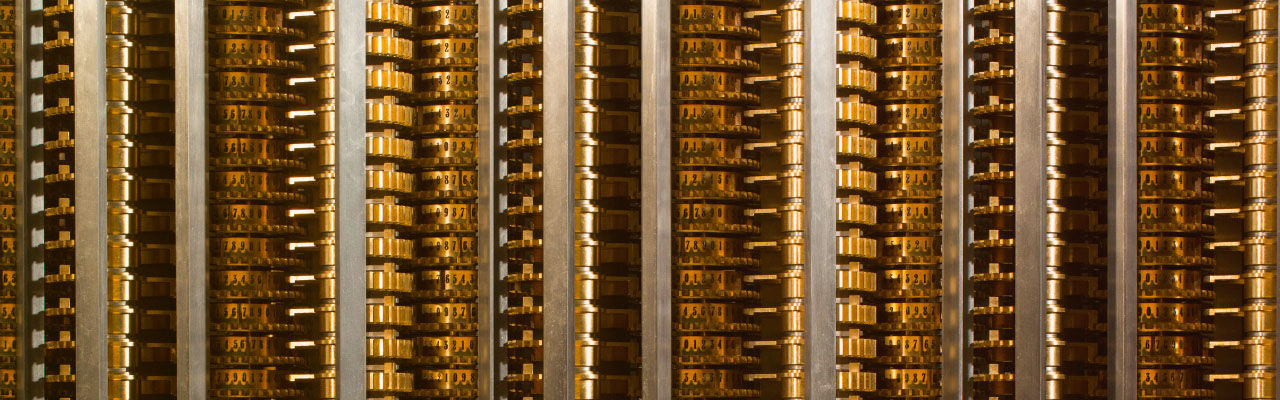

The London Science Museum’s replica of Charles Babbage’s “Difference Engine #2,” (1847-9), one of the earliest mechanical computers.

The London Science Museum’s replica of Charles Babbage’s “Difference Engine #2,” (1847-9), one of the earliest mechanical computers.

A Nineteenth Century “Digital” Humanities?

Reading Ben Breen’s blog post on the experimental techniques available to historians today, including digital tools like data visualization, OCR, ebook databases, Google Ngrams and culturomics, I was struck by a sense of déjà vu. Suddenly I remembered having read about similar debates in the late nineteenth century. Since my doctoral degree was on the history of the social sciences, with such concentration fields as the history of Victorian social thought, I spent countless afternoons crouching in dark carrels in libraries reading Victorians like William Jevons, Adolph Quetelet, Francis Galton, and Henry Thomas Buckle.

If Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Karl Marx narrated their way through political economy, Javons experimented his. Javons thought that value was completely detached from the labor that went into producing an object. For him, value depended entirely on use. His major insight was that utility seemed to increase and diminish following a curve that could be graphed and rendered into an equation: the law of marginal utility. The graphics and the math were so powerful that after Javons political economy dropped the “political” and became simply “economics”, a “science” that like astrology requires practitioners to use math.

In the Victorian era, the smart and the curious fell in love with experimental techniques that spelled the end of narrative. Numbers, graphics, and data took over. The Belgian astronomer Quetelet found strange regularities in quantifiable human events: the number of letters that got lost or misplaced in the Parisian postal service, for example. Statistics seemed to describe striking numerical patterns in the way societies behaved: Societies and collectivities had laws of their own. The hope of understanding these laws had consumed August Comte a generation before Quetelet. Yet Comte narrated his way through the laws, producing several thick volumes on “Sociology,” a word Comte coined. Quetelet had no patience for Comte’s longwinded narratives. Statistics, a science of numbers, graphics and data, was the shortcut.

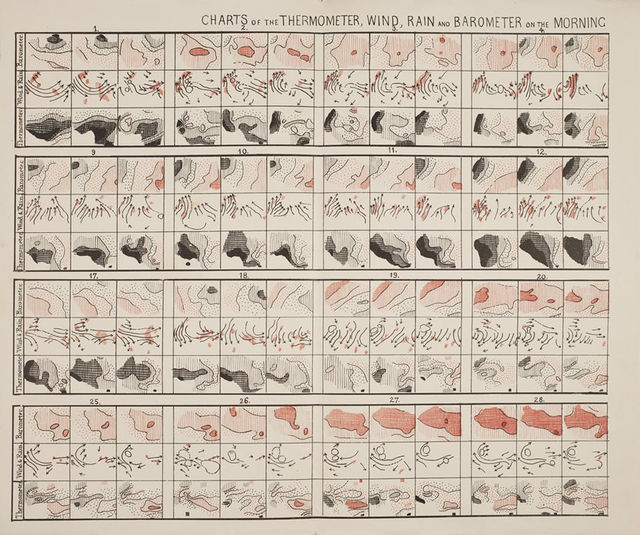

Galton doubled down on Quetelet’s insights and transformed everything in sight into graphs and numbers: fingerprints, faces, skulls, “intelligence.” He invented IQs and craniometry. Galton and his Victorian peers became enamored of numerical regularities to be found in large “databases.”

A weather chart from Galton’s Meteorographica (Macmillan, 1863). Image courtesy of the Wellcome Trust

Yet it was up to Buckle to transform history into a “science.” Buckle sought to do for history what Javons did for political economy and Quetelet and Galton did for sociology, namely, do away with narrative. Statistical regularities would yield true, deep understanding onto the changing behavior of collectivities though time. Buckle represented the triumph of statistics over narrative among historians.

Has anybody read Javons, Quetelet, Galton, or Buckle lately? I read them often some 20 years ago; every afternoon they waited for me patiently on sagging old bookshelves. Eventually I took my seminars on Victorian social thought and passed my qualifying exams. I have to confess that ever since, I have not opened their dusty old books again.

However, as evidenced by the profusion of historians and other academics working in the digital humanities today, their legacy is all around us.