David Bailly, Self-Portrait, 1645, sourced from the Rocaille blog.

David Bailly, Self-Portrait, 1645, sourced from the Rocaille blog.

Responses to Cabinets of Curiosity

Our November 28 blog post on Cabinets of Curiosity elicited a range of comments from as far away as Sweden and Italy. Below I’ve collected some of the more notable.

On our Facebook page, historian Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra offered an interesting comment on the human face of curiosity cabinets:

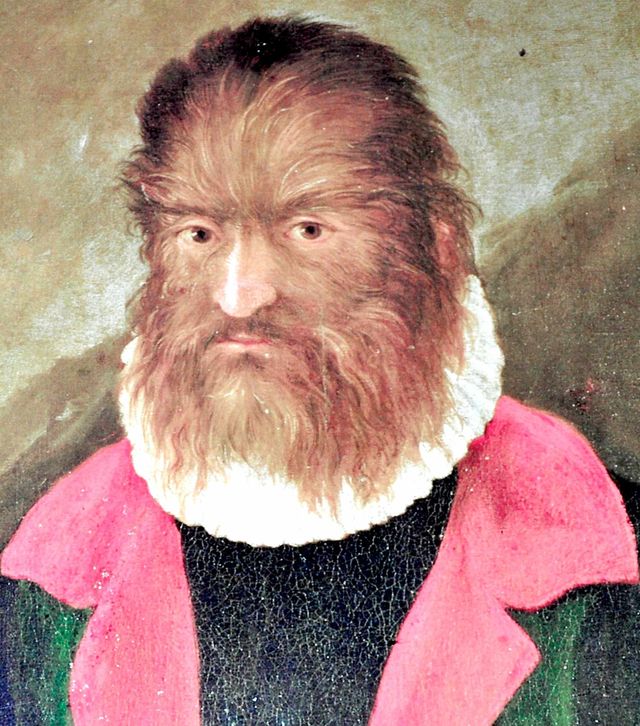

I feel like honoring the humans in these collections: Petrus Gonsalvus, doubly monstrous because he was wolf-like and a dwarf, a Canarian item in Margaret of Parma’s cabinet in Antwerp; the family of spotted albinos in the Portuguese court from Pernambuco. There is the moving letter of Isidoro Martín y Morales addressed to Charles III and Charles IV, respectively, now at the Archive of the Indies (AGI, México, 3143). Born with a legless torso, Isidoro first begs the king to be compassionate and send him money. Years later a desperate Isidoro volunteers to go to Madrid to enhance the cabinet of curiosities. Somehow Mexico, Brazil, and Tenerife became suppliers of men and things for the Wunderkammer. Worth remembering in this age of virtual cabinets.

This featuring of human beings is an aspect of early modern curiosity cabinets that I neglected to mention, and it is surely the most unsettling and saddening aspect of the phenomenon. Below is a portrait of Petrus Gonsalvus, the Canary Islander born with hypertrichosis (hirsutism) who was traded between various European royal houses as a curiosity. The preserved remains of “monstrous” or otherwise unusual humans also featured prominently in these displays—in fact, the library of St. Johns College at Oxford University apparently possessed the tattooed skin of Giolo, a Filipino man kidnapped by the privateer William Dampier until the early 20th century. A macabre and sad reminder that curiosity cabinets came from the age of slavery as well as the era of Rembrandt and Vermeer. And also, I think, another link with the present—contemporary readers of the Internet, after all, love the “monstrous” at least as much as Europeans of the Baroque era did.

Petrus Gonsalvus as portrayed in a painting from the Chamber of Art and Curiosities in Ambras Castle in the Netherlands. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, on Twitter, Annalisa, an art history graduate student in Rome, linked me to her wonderfully illustrated blog post on Why a Wunderkammer is Kitsch. Annalisa writes on her curiosity cabinet-inspired site:

It’s a little bit anachronistic to define [as] Kitsch a Wunderkammer, but they share the same accumulation principle. An eclectic space where objects are considered for their singularity, completely disconnected from the context.

Likewise, The Vault, a new blog of “historical treasures, oddities and delights” on Slate, had this to say:

Also on Facebook, Lindsey Fitzharris of the Chirurgeon’s Apprentice blog (and research fellow at the University of London) linked to the post, which solicited the following comment. (I’ve cropped it for length—it goes on like this).

The contents of a curiosity cabinet:

1) A cup and saucer made of cherry stones

2) A piece of Queen Catherine’s skin

3) An asbestos handkerchief

4) The Lord’s Prayer written on a silver penny

5) A pair of dice used by the knights’ templar

6) A purse made of spider’s web

7) Consecrated wafers

8 ) A pair of garters from South Carolina

9) A crucifix made by a French prisoner at Winchester, from the bones in his food

10) A very curious young mermaid fish

11) The head of an Egyptian

12 Instruments for scratching the Chinese ladies’ backs

13) Mary Queen of Scots Pin-cushion

14) A necklace of Job’s tears

15) Bones from a spring called Boney Well near Ludlow.

16) The pizzle of a raccoon

17) A statue of Priapus god of Gardens

Although fascinating, this list also demonstrates the pitfalls of a Wunderkammer-like approach to knowledge: because it has been decontextualized and passed around the web “unlabeled,” as it were, I initially had trouble finding out where this list was actually from, or if it indeed was even genuine! After some digging, it seems to be from the Chelsea curiosity cabinet of one Don Saltero (or Salter), an enterprising Londoner circa 1700.

Finally, as Amy Kohout pointed out, I was remiss not to mention the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, a modern-day curiosity cabinet if there ever was one (here’s a link to the book about it). And, closer to (my) home on the east side of Austin, TX, I wanted to mention the Museum of Ephemerata, a charmingly odd-ball Wunderkammer that a husband and wife maintain in the front rooms of their house. Highly recommended!