The earliest spam email, sent by a Digital Equipment Corporation tech named Carl in spring of 1978.

The earliest spam email, sent by a Digital Equipment Corporation tech named Carl in spring of 1978.

The Deep History of Email Scams [Updated]

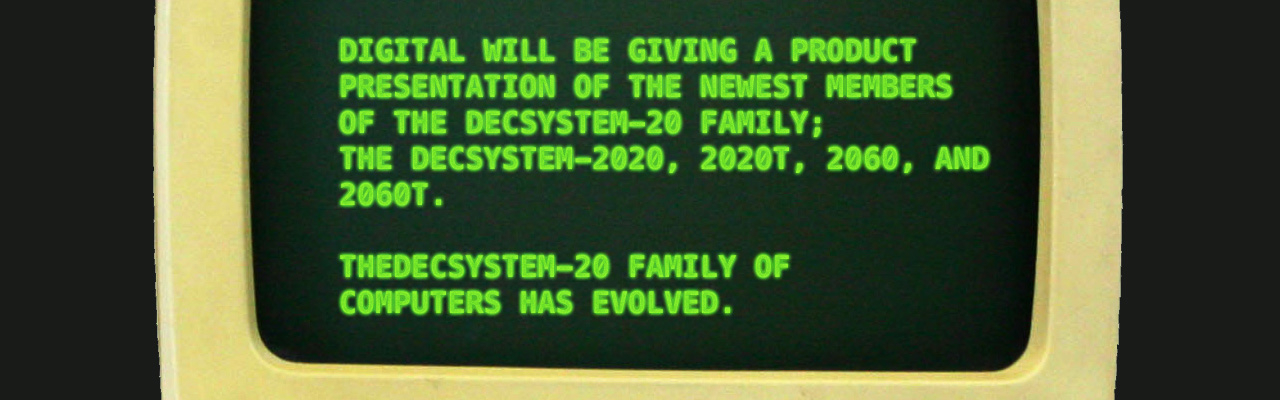

In May of 1978, a computer tech named Carl Gartley typed an email into the flickering, black and green screen of an early computer terminal. The company he worked for, Digital Equiment Corporation (DEC) was eager to publicize its new computers to the users of Arpanet, the network that would grow into the Internet.

The email’s address list is a catalog of the scientific and government elite (at places like UCLA, PARC, and the Rand Corporation) who sent emails back in the late 70s. The message itself is not exactly a model of the writer’s art, but it gets the point across:

DIGITAL WILL BE GIVING A PRODUCT PRESENTATION OF THE NEWEST MEMBERS OF THE DECSYSTEM-20 FAMILY; THE DECSYSTEM-2020, 2020T, 2060, AND 2060T. THE DECSYSTEM-20 FAMILY OF COMPUTERS HAS EVOLVED FROM THE TENEX OPERATING SYSTEM AND THE DECSYSTEM-10

COMPUTER ARCHITECTURE…

WE INVITE YOU TO COME SEE THE 2020 AND HEAR ABOUT THE DECSYSTEM-20 FAMILY AT THE TWO PRODUCT PRESENTATIONS WE WILL BE GIVING IN CALIFORNIA THIS MONTH.

This was, as NPR reported on its 30th anniversary, the first spam email in history.

The email users who received the message were appalled and confused in a way that seems quaint today. “This was a flagrant violation of the use of Arpanet,” huffed one, with these famous last words: “Appropriate action is being taken to preclude its occurrence again.”

Arpanet, its worth remembering, was a U.S. Government property at the time, “not intended for public distribution although not ‘top secret’ either,” as another response to the DEC spam put it. In another interesting response, a lone defender of the spam argued for a freer use of the email medium. In the process, this devil’s advocate made what is probably the earliest reference to internet dating: “Would a dating service for people on the net be ‘frowned upon’ [by Arpanet administrators]? I hope not.”

On the whole, though, spam was hugely unpopular among these earliest denizens of the web. It was a first glimpse of a future where the communications of digital gatekeepers selected by government agencies and elite universities might become swamped by a horde of anonymous jerks and unscrupulous capitalists.

In other words, it was the harbinger of the Internet as we know it.

As historian Robert Whitaker explores in our article “Proto-Spam”, however, the history of long-distance trolling stretches back to the Victorian era.

Whitaker is an expert in the scam known as the Spanish Prisoner Scheme. “In this confidence trick,” he explains,

the criminal contacts the victim offering a large sum of money in return for a small advance of funds that the criminal—posing as a distressed yet reputable person—cannot provide because of some impediment (usually imprisonment or illness)… The successful prisoner is one that can combine a too-good-to-be-true offer with a compelling narrative that the victim can, literally, buy into.

As Whitaker notes, such a scheme appears at first glance to be a modern invention, the provenance of Nigerian email scammers and shady characters on Craigslist trying to get you to wire them money. Yet the human desire for lucre—and unscrupulousness about how we obtain it—is more or less a universal, and as he notes, the main difference between these twenty-first century cons and those of the Victorian period is one of delivery method.

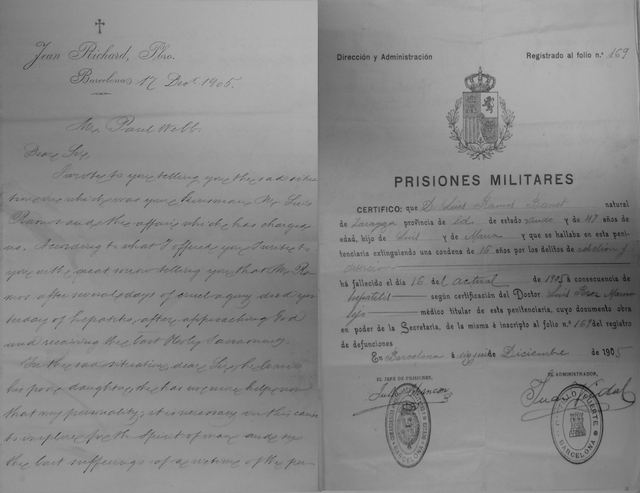

Whitaker has uncovered documents from 1905 supposedly written by a distressed Spaniard named Luis Ramos and Jean Richard, a prison chaplain. Addressed to a London shopkeeper named Paul Webb, these letters are straight out of the scam email playbook: Ramos claims to have “property valuable to £37.000” deposited “in a sure English Bank,” and he’ll give Webb a cut if the Englishman agrees to send Ramos a small amount of money to bail his fourteen-year-old daughter out of prison.

This early scam letter is also very much of its time, though: Whitaker shrewdly observes that it resembles a Dickensian novel, complete with an imprisoned child who “seeks a new guardian to share a large inheritance amidst the backdrop of continental political intrigue.”

These 19th-century letters also have an imperial context that links them not only with the Dickensian novel, but with the Nigerian email scams of today. A striking number of these early letters hailed from Spanish-speaking countries, lending an aura of exotic corruption to their narratives. In his book Spam: A Shadow History of the Internet, NYU media professor Finn Brunton uncovered a 1910 New York Times account that described Havana as a common point of origin for Spanish Prisoner letters in the preceding decades, “but it is not used now, probably because communication with it is so frequent and easy.”

Indeed, the 1910 article cited by Brunton is almost uncanny in the way that it matches contemporary Nigerian scam emails:

The letter is written… as fairly well-educated foreigners speak English, with a word mispelled here and there, and an occasional foreign idiom. The writer is always in jail because of some political offense. He always has some large sum of money hid.

As Brunton writes, both the Spanish Prisoner and Nigerian scams rely upon the vagueness of tropical spaces in the Western imagination, as well as their reputation for “political chaos” and untapped riches. Post-colonial prejudices, in both the declining British Empire of the 1910s and the declining American hegemony of the 2010s, might be regarded as a necessary precondition for scams like the Spanish Prisoner letter.

Yet the rise of mail fraud and proto-spam owed most to technological change. Following 1897, when the directory Who’s Who began including the mailing addresses and biographies of prominent Anglo-Americans, it became easier for unscrupulous capitalists to identity potential marks. “The pomposity and vanity of the British elite listed in Who’s Who,” Whitaker notes, “could place them in harm’s way.”

In short, the globalization of personal data via compendia like Who’s Who and the earliest phone books gave rise to a new form of confidence game: Hucksters no longer had to fool their marks in person. They could now exploit global networks of communication to trawl for gullible souls in countries they might never visit—and they could even identify individuals whose biographies hinted at a vein of narcissism or greed that could be profitably mined. And people would fall for it, then as today, because, Whitaker writes, not only are we “always looking for easy money, but we are perhaps even more eager for a good emotion.”

Check out the rest of Whitaker’s piece to learn more about the letter and other early scams, or read this post based on his research into Interpol and the Church of Scientology—another pioneer in the shady world where technology and confidence games collide.

Update, November 3, 2013: NPR’s *On the Media program has interviewed Appendix contributor Bob Whitaker about his article on the Spanish Prisoner scam.*