Proto-Spam: Spanish Prisoners and Confidence Games

Dearest Readers, I beseech you,

Please accept this humble letter from a poor stranger seeking your help. Although we are not acquainted, I have heard word of your excellent taste in historical writing from a consumer analytic program that knows you quite well. I write to you in the most desperate of circumstances to ask you to help secure my freedom. I sit now in a cell within a modernist dungeon known as a ‘library,’ imprisoned after failing to heed common sense and attending graduate school in the humanities. The machinations of my enemies have forestalled correspondence with my next of kin, but the editors of The Appendix have kindly agreed to forward this letter to you. My imprisonment prevents the publication of my historical monograph, which would surely collect no less than $100,000,000,000 on the open market. I offer a portion of this sum to you in return for a small advance on your part. I will discuss the specifics of my request at the end of this letter, but please begin by considering the following sample of my final work.

My writing concerns the history of advance fee fraud, better known as the “Spanish Prisoner Scheme.” In this confidence trick, the criminal contacts the victim offering a large sum of money, or other comparable treasure, in return for a small advance of funds that the criminal—posing as a distressed yet reputable person—cannot provide because of some impediment (usually imprisonment or illness). Readers with an email account have undoubtedly encountered a variation of this scheme. The proliferation of the Nigerian Letter or 419 scam during the late twentieth century encouraged the development of spam filters. While early iterations of this electronic grift were accompanied by preposterous stories involving Nigerian royalty, recent versions have made the scheme more credible by hacking the email accounts of the law-abiding and using their lives as the basis for letters sent to individuals on their contact list.

The success of this con may appear, at first, to rely entirely on elements intrinsic to an Internet age awash in attention-seeking anonymity. We hear stories almost daily about marks getting duped by a comment troll, twitter bot, or catfish relationship. Yet compared to the historical versions of this swindle, our current Spanish Prisoners only differ in their method of delivery. The past is filled with Manti Te’os, and many of them suffered fates much worse than a broken heart and declining NFL draft stock. The enduring success of the prisoner swindle relies as much on the mark’s sentimentality and need for emotional connection as it does on their desire for a quick buck. The successful prisoner, then, is one that can combine a too-good-to-be-true offer with a compelling narrative that the victim can, literally, buy into.

One of the best sources for Spanish Prisoner letters from the past can be found in the files of the Foreign Office (FO) and Metropolitan Police (MEPO) at the British National Archives. Britain has long been a target of the Spanish Prisoner, dating back at least to the Peninsular War in the early nineteenth century. Waves of the scam hit the island every twenty years or so afterward, as clever criminals used the backdrop of successive Spanish civil wars, known collectively as the Carlist Wars, to spin tales of wrongful imprisonment, political intrigue, and hidden treasure for their victims. It should be noted that many of these criminals probably did not write from Spain. In fact, as some members of the Met surmised, many of these “prisoners” were writing from England. Spain’s criminal reputation then, not unlike Nigeria’s reputation today, was as much the indirect result of endemic conflict as of actual wrongdoing. Nevertheless, the fact that some of these first letters originated from Spain makes the prisoner scheme one of the earliest and most enduring examples of international crime.

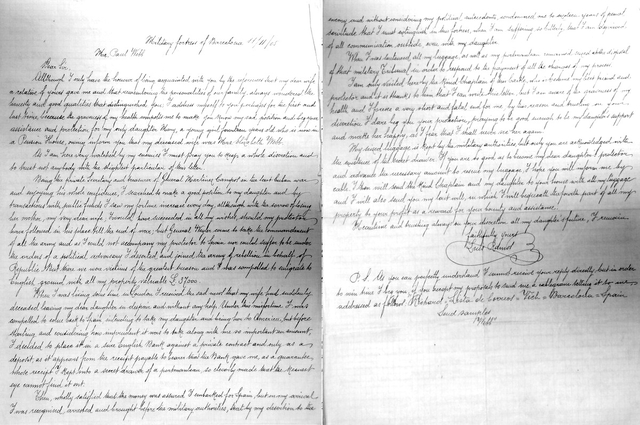

What is remarkable about these letters from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is their level of craftsmanship, both with regard to the prisoner’s narrative as well as the physical trappings of the letters themselves. Take for instance the series of letters sent to Mr. Paul Webb, a Sloane Street shopkeeper, in 1905. Using above average diction and writing in a pleasant cursive, the prisoner “Luis Ramos” implores Mr. Webb to send funds to assist and protect his daughter, “a young girl of fourteen years old who is now in a Prison House.” Ramos, drawing from recent history, explains that he was the private secretary of General Martinez Campos during “the last Cuban war,” but owing to the replacement of Campos by Valeriano Weyler—“a political adversary”—Ramos left the army and joined the rebellion on behalf of the republic. Thanks to “the greatest treason,” Ramos was “compelled to emigrate to English ground with all my property valuable £37.000.” He decided to return home after the death of his wife in order to take care of his daughter Mary. Ramos tells Webb that he left for Spain after depositing his money “in a sure English Bank,” but was intercepted by the authorities upon disembarking and placed in a military prison in Barcelona. Complaining of an illness and certain that he will have “a very short and fatal end,” Ramos begs Webb to send funding that will release his daughter and his confiscated luggage, which contains the receipt for his English bank account in a secret drawer.

Webb responded to this correspondence by telegraphing Ramos’s designated intermediary, a prison chaplain named “Jean Richard,” to inquire about the situation. This telegraph led to another Ramos letter, which reiterated his impending death as well as his fear that his political enemies would surely find and punish his daughter if help did not arrive soon. Ramos also warned Webb not to alert authorities in Spain or Britain as it would put his child at risk. This second Ramos letter, however, broke the drama, as it was sent to Webb, but addressed to a Mr. Thomas McGill, no doubt another potential target for the scheme. The criminal compounded the mistake by sending the same letter, now addressed to Webb, four days later. A follow-up letter was sent the next week in which Ramos wrote, “I feel that my life is going away…I have made my will by which I name my daughter my only heiress, appointing you her guardian.” He would “write no more, [as] neither my head nor my hand allow it to me; I pray you to forget not my prayer and to abandon us not as we have but you to save my poor Mary of her distress.”

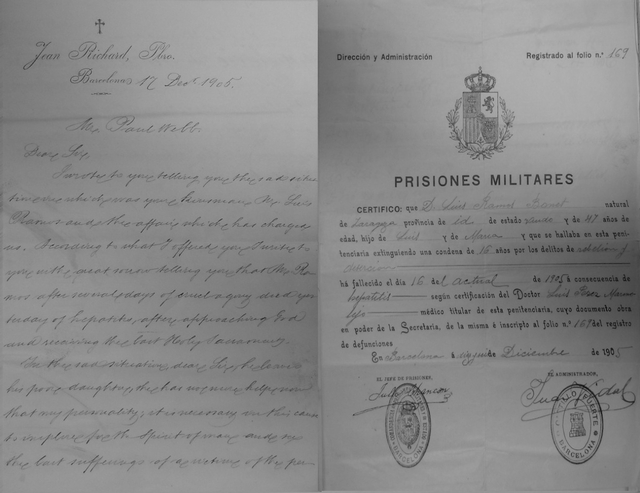

That same day, Webb received a message from “Jean Richard,” the impostor prison chaplain, written in a different hand on what appears to be church stationery. This letter verified the points of Ramos’s story, and encouraged Webb to act, promising “God will protect you.” After nearly a month of silence, Richard wrote again to tell Webb that “Mr. Ramos, after several days of cruel agony died yesterday of hepatitis, after approaching God and receiving the last Holy Sacraments.” The chaplain included in this letter a copy of Ramos’s will, his death certificate, and a Spanish newspaper notice regarding the prisoner’s death. This final letter was the first to mention the advance needed from Webb in order to free Mary and Ramos’ luggage: £59. Webb, however, did not fall for the ruse, and reported the correspondence to the Metropolitan Police (Met) the following week.

In the “Ramos” letters we have all the elements of a classic Victorian drama: faced with the death or imprisonment of parents, a child seeks a new guardian to share a large inheritance amidst the backdrop of continental political intrigue. The drama is reinforced by the educated content and sophisticated appearance of the writing as well as a seemingly genuine collection of supporting documents. Webb’s telegraph after the first letter shows that, even if he was still skeptical, he believed the correspondence could be real. The criminal, though, squandered his chance by addressing the next letter to the wrong person.

“Ramos” made even worse mistakes, however. After receiving a long and detailed “Ramos” letter addressed to Mr. William Topley, the partners of Wm. Topley & Sons wrote to Scotland Yard informing them of the correspondence and explaining that the company’s namesake had been dead for over twenty years. A year later, Mrs. Mary Bates brought the police a similar letter addressed to her husband, who had passed away seven years before. Mr. Harry Robertson of Mincing Lane wrote the Met with another example in 1908. Robertson explained that this was the fourth such letter he had received in his life, but the first to switch his Christian name and surname (Dear Robertson Harry), and to claim familiarity through the prisoner’s deceased wife (Mrs. Mary Harry)—a “new and rather amusing” touch, Robertson smirked. Other potential victims were not so amused, and went to great lengths to see that something was done. William Thomlinson, a mining executive based in British Columbia, wrote to Scotland Yard complaining about a prisoner letter and declaring, “if you are in touch with the authorities in Spain, perhaps these fakers can be caught and put to honest work, in jail.”

Yet for the many of Ramos’s letters that missed their mark, just as many found willing victims. “About 16th January last,” wrote Superintendent Gordon of the Stirlingshire Constabulary, “Mrs. Margaret McAllister…received letter No. 1 of the enclosures [from “Jean Richard Pbro”]…and cabled in reply that she agreed to co-operate with the writer.” After receiving additional letters from Richard, “she sent a cheque for £60 payable to Jean Richard Pbro…She received letter No.7 dated 13th February in acknowledgement of the cheque; but although she immediately thereafter wrote asking for more information, she received no word.” Gordon wondered if “there is a chance of getting at Jean Richard Pbro,” and if “the Barcelona Police would act much more readily for [the Met] than for [Stirlingshire].” “It seems a pity,” Gordon continued, “that there should be no way of getting at that scoundrel.”

A similar situation confronted George and Mary Sophia Vooght of Cricklewood, who

received a letter from a man signing himself as Alvaro de Guzman, stating he was in Prison at Murcia, Spain, undergoing twelve years imprisonment…and that he had a daughter who was in a college in Spain who he was anxious to have sent to England to be educated and to live under the care of Mr. Vooght.

Guzman claimed to be a relative of Vooght through Guzman’s deceased wife Mary. “As Mr. Vooght had a sister Mary whom he had not seen for many years,” Sergeant W. Kemp reported, “he induced his wife to write to Guzman, offering to accept the girl Amelia, and have charge of her.” Guzman replied by requesting that Vooght send £200 to his intermediary, Chaplain Jose Roig, in order to secure the girl’s safe passage and the collection of her inheritance. Mrs. Vooght, becoming suspicious, wrote to a Magistrate in Murcia, but received a letter from Jose Roig, stating that this letter had been handed to him and that Guzman had passed away since their last exchange. Roig wrote that he needed £115 to help process the passage of Guzman’s estate to his daughter and her new guardians. Mrs. Vooght responded by sending the money, but did not receive a reply. Mr. Vooght then asked a friend to write to Roig asking for an explanation. Roig replied to this letter by “stating he was in Prison for some offence he could not explain, but required £35 more to enable him to bring Amelia to England.”

Mrs. Vooght went to the police after this letter, at which point Sergeant Kemp “informed [her] the whole thing was a swindle and that we could not assist her, beyond forwarding the documents to the British ambassador at Madrid.” The British Embassy in Madrid, when they received word of these frauds, forwarded notices on to Spanish authorities, but warned that individuals living at the local addresses used by the criminals often “turn out to be mere innocent accessories to the fraud, who can prove their ignorance of the contents of the letters sent to their address; while the real swindlers remain uncaught, and continue their correspondence under a different name.” The ability of these swindlers to intercept incoming letters from marks before they reached their local destination—as was the case with Mrs. Vooght’s letter to the magistrate of Murcia—suggests that the “prisoners” were postal employees that handled foreign deliveries.

While most of these criminals eluded capture, authorities sometimes successfully foiled their correspondence campaigns. In one instance, the Spanish ambassador to Britain, Marquis de Villalobar, sent a list of addresses of potential British victims to Metropolitan Police Commissioner Edward Henry. The Met used this list to prevent at least one fraud aimed at Mr. Charles Clark, a London cycle dealer, who had already sent a positive reply to his first prisoner letter, but fortunately had not included any money. On other occasions, members of the public who suspicions had been aroused helped the police. In 1910, a member of the advertising department of The Daily News warned police that he had received a series of strange notices for inclusion in the paper’s classified section and believed they could be related to fraud. The Met followed up with the individuals that had placed these ads, and found that they had each received a prisoner letter that instructed them to place their reply in the newspaper. The police responded by placing warnings regarding this fraud in post offices across the country. Of course, even with these precautions and examples of public vigilance, the letters continued to arrive. Not unlike victims of the scheme today, those who were duped often left the incident unreported out of embarrassment.

As can be surmised from the Met’s files, the Spanish Prisoner Scheme witnessed a notable surge in Britain at the beginning of the twentieth century. This increase was undoubtedly influenced by the greater ease and reliability of cross border communication as well as the recent Spanish-American War. The technique of using war as part of the dramatic background for these frauds continued throughout the twentieth century, most obviously during the Spanish Civil War, but also earlier during the First World War, when several prisoners claimed to be wealthy Belgian refugees who fled to Spain after the Siege of Liège. Certainly, this type of opportunistic criminality is not unfamiliar to modern readers in the aftermath of Katrina and Sandy.

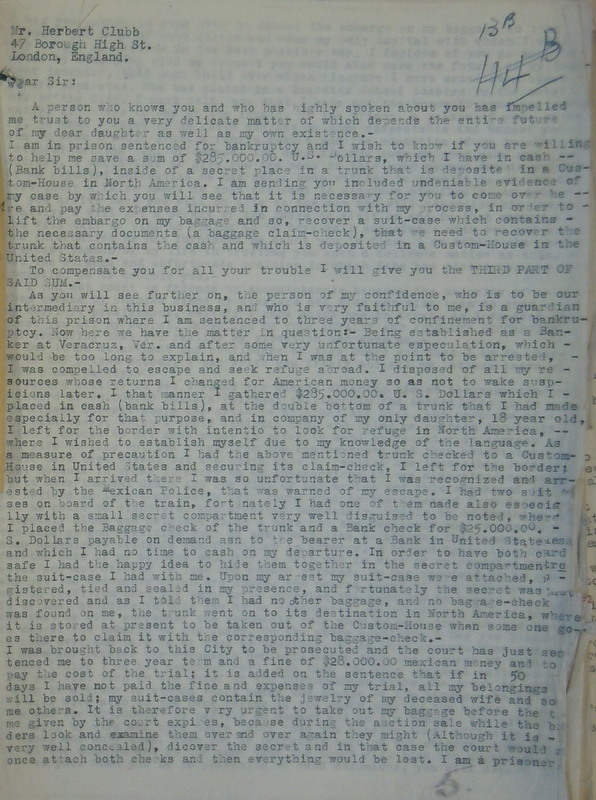

Another development specific to Britain—though part of the long history of social media—played an important role in that era’s upsurge of prisoner letters. Beginning in 1897, Who’s Who—a publication you might call a precursor to Facebook—began to print fuller descriptions of prominent individuals that included short biographies and vitas alongside official addresses and club memberships. Much like your oversharing friends today, the pomposity and vanity of the British elite listed in Who’s Who could place them in harm’s way. That fact was evident in a series of prisoner letters from Mexico collected by the Metropolitan Police during the 1930s and 1940s. “Vincente Olivier” of Mexico City sent dozens of letters to the cream of British society, including prominent business executives, military officers, ministers, and politicians. “A person,” Olivier’s letters began, “who knows you and who has highly spoken about you [i.e. Who’s Who] has impelled me trust to you [sic] a very delicate matter of which depends the entire future of my dear daughter, as well as my very existence.”

Olivier’s letters followed the basic formula of Ramos’s correspondence from decades earlier (prison, orphan, intermediary), but Olivier’s typewriter allowed him to send a larger number of letters. Additionally, his use of Who’s Who gave him a steady source of potential targets and helped him avoid making Ramos’s frequent mistake of writing to the deceased. Although the Met never determined how Ramos chose his targets, his constant references to the deceased relatives of his letters’ recipients could be a sign that the criminal laboriously scanned local death notices and obituaries for mention of residents with ties to Britain. Olivier’s letters anticipated the modern spammer’s preference for quantity over quality in prisoner letters. His work was hurried and only occasionally included the elaborate narratives and supporting documents developed by Ramos and other swindlers decades earlier. Ramos had been a criminal, but with a class and skill utterly lacking in the average bot scammer today. The effort he undertook in order to commit crime almost makes you wish you could give him money, if for no other reason than to reward him for his dedication to his nefarious work.

Though Olivier’s letters lacked Ramos’s panache, they retained the tactic of appealing as much to the victim’s emotions and sentimentality as to their wallets. For those victims recently bereaved or simply lonely, the ability to lend aid to a dying man and his innocent daughter (who was presented as a possible distant relative) often led to a response. Certainly, other victims were taken in by the opportunity for fortune or by the drama of political intrigue that these letters provided. More often than not, however, successful letters worked because the victims believed the story and felt that they played a crucial role in it. Earlier this year, people expressed amazement that Manti Te’o could be in love with someone he’d never seen in person; imagine the public incredulity if he had agreed to be the guardian of a non-existent orphan child. And yet it seems equally possible. We are always looking for easy money, but we are perhaps even more eager for a good emotion.

Here ends my story. I would gladly share the remainder of my narrative with you in return for a formal book contract from an academic publisher that I can use to escape my imprisonment and secure my future wellbeing. If you are willing and able, please forward said contract to my intermediary Robert Whitaker, courtesy of The Appendix. Please hurry! My graduate student funding runs short!

Your Most Insincere Servant,

Caraboo Ponzi Madoff-Meinertzhagen III, Esq.