This is what an authentic book of magical spells looks like.

This is what an authentic book of magical spells looks like.

The Key of Hell: An Enlightenment Sorcery Manual

Cyprianus was, by all accounts, a shady character. In her book Remedies and Rituals: Folk Medicine in Norway and the New Land, Kathleen Stokker writes that medieval Scandinavians spun tales of a Dane named Cyprianus who was so evil that Satan cast him out of hell: “This act so enraged Cyprianus that he dedicated himself to writing the nine Books of the Black Arts that underlie all subsequent Scandinavian black books.”

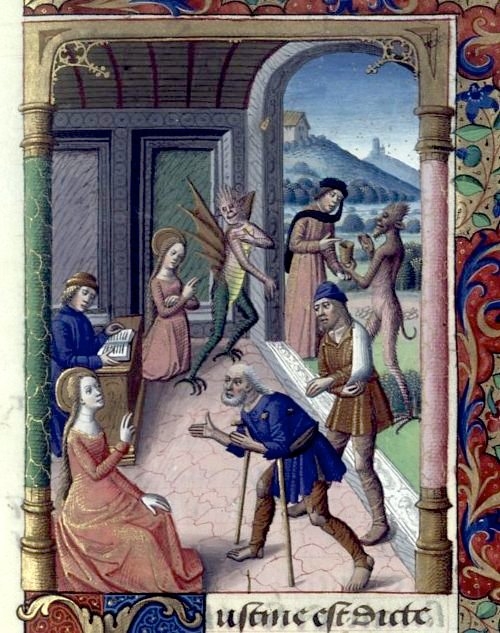

Bizarrely, another tradition maintained that the true Cyprianus was “a ravishingly beautiful, irrestistibly seductive, prodigiously knowledgeable, pious Mexican nun.” And yet another tradition traces the name back to St. Cyprian of Antioch, a powerful Greek wizard who was famed as a demon-summoner before converting to Christianity. Despite Cyprian’s saintly later life, medieval authors appear to have been more interested in the demon part—here’s a 15th century French painting of Cyprian striking up a bargain with two devilish characters, for instance.

What we know for sure is that “Cyprian” became a common pseudonym for people at the edges of society who were trying to do real black magic. And thus we find “Pseudo-Cyprianus” listed as the author of this jaw-dropping book of magical spells from the late 18th century, which the Wellcome Trust has just made public domain. The title is Clavis Inferni (The Key of Hell) and the images are magnificent and thrillingly mysterious:

“Maymon—a black bird—as King of the South.” Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, late 18th century. Wellcome Images

“Uricus—a red-crowned and winged serpent—as King of the East.” Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, late 18th century. Wellcome Images

“Egyn—a black bear—like animal with a short tail—as King of the North.” Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, late 18th century. Wellcome Images

“Paymon—a black cat-like animal with horns, long whiskers and tail—as King of the West.” Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, late 18th century. Wellcome Images

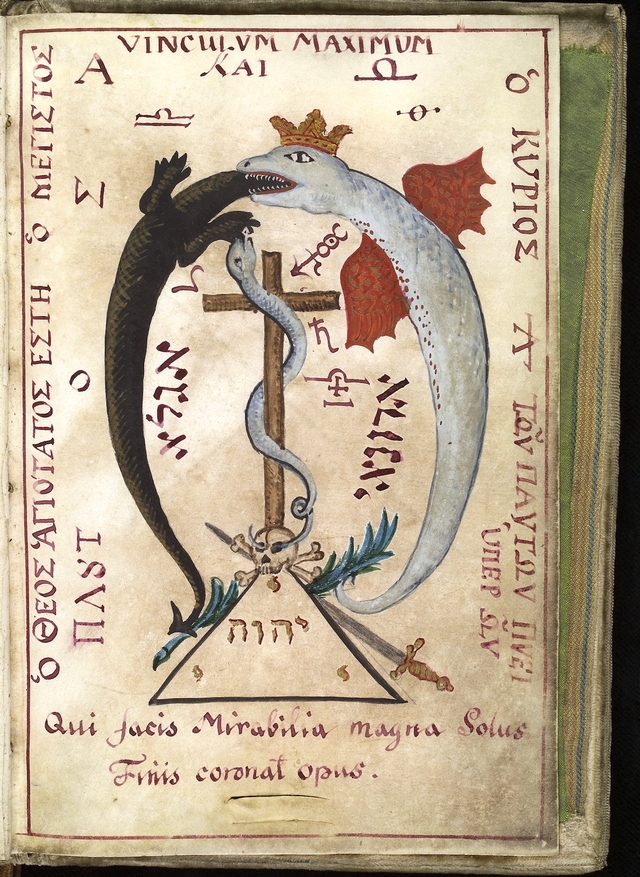

“Ink and watercolour showing a red-winged dragon wearing a gold crown and devouring a lizard.” Cyprianus, Clavis Inferni, late 18th century. Wellcome Images

The sword and branch in that last image (my favorite of the bunch) probably refer to the common iconography of God’s twinned powers to create destruction or peace. The Latin text reads Qui facis mirabilia magna solus finis coronat opus. I translate this to something like “You who act alone with great miracles [or miraculous things]: the end shall crown the work.”

Beyond this type of basic iconographic reading, those looking for reliable answers about the origin or meaning of these images will be disappointed. The Wellcome Trust itself gives a description of the book that sounds like it’s lifted verbatim from Harry Potter:

Cyprianus is also known as the Black Book, and is the textbook of the Black School at Wittenburg, the book from which a witch or sorceror gets his spells. The Black School at Wittenburg was purportedly a place in Germany where one went to learn the black arts.

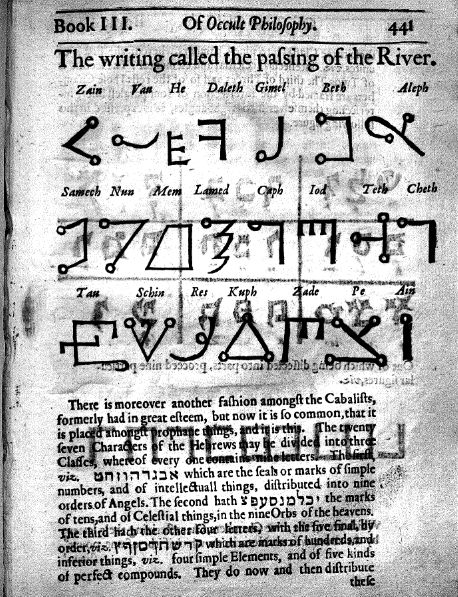

Hoping to find out more, I posted about this bizarre text on my blog Res Obscura three years ago, and some knowledgeable fans of early modern magic came out of the woodwork to help me with translations. One pointed out to me that the cipher alphabet being used here is Cornelius Agrippa’s Transitus Fluvii “Passing through the River” script, adapted from Hebrew by the famed occultist in 1510 (fun fact: it was also used in the Blair Witch Project):

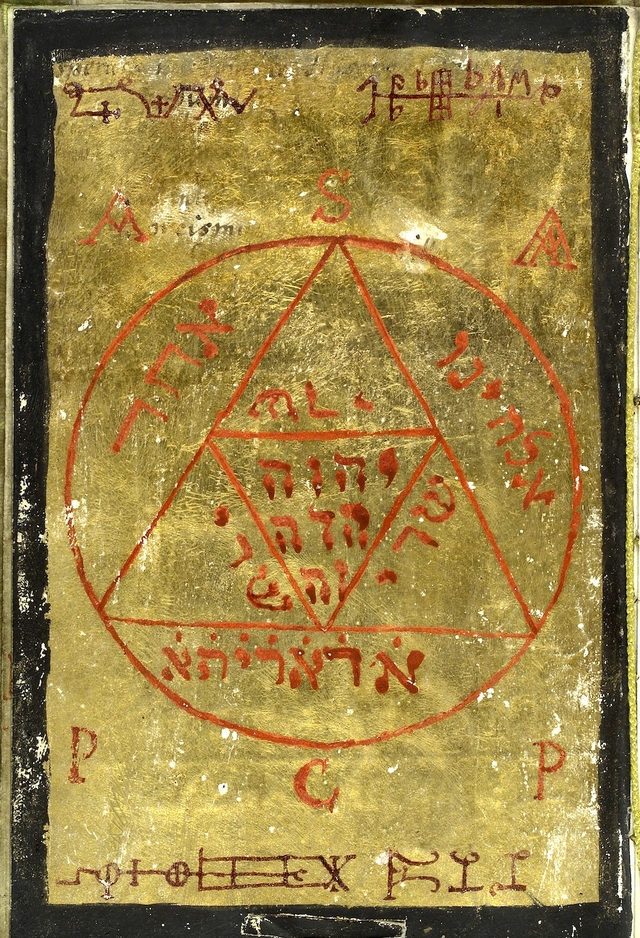

The book also uses actual Hebrew, such as in this gold-leaf sigil. (A challenge to readers: can anyone translate this?)

For the most part, though, these images and writings reach the twenty-first century without context, and without a key to unlock them. Their authors intended it that way. Only the elect, or those with direct knowledge passed down from a magical practitioner, were thought to be worthy of understanding books like this. Contemporary practitioners of “magick” might try to unlock them, and historians might successfully contextualize them, but in a very real way, these books will always be ciphers to us.

That doesn’t mean that they’re relics of a “dark age” of superstition and ignorance, however. As Appendix contributor Lisa Smith wrote in her article “Bespelled in the Archives,” the desire to perform magic didn’t die out with the Enlightenment: spellbooks stuffed with black magic actually proliferated in the same period that Voltaire, Hume and Kant were celebrating the dawn of reason.

And this wasn’t necessarily a contradiction: in his fabulous book The Dark Side of the Enlightenment, Princeton professor John Fleming points out that magic and Enlightenment thought could coexist. Worldly sorcerors like Count Cagliostro, Fleming argues, were actually made possible by the globalization of the 18th century, namely “extensive and rapid international communication of ideas” via the Republic of Letters and the “well-organized international intellectual elite of Rosicrucians and Freemasons.”

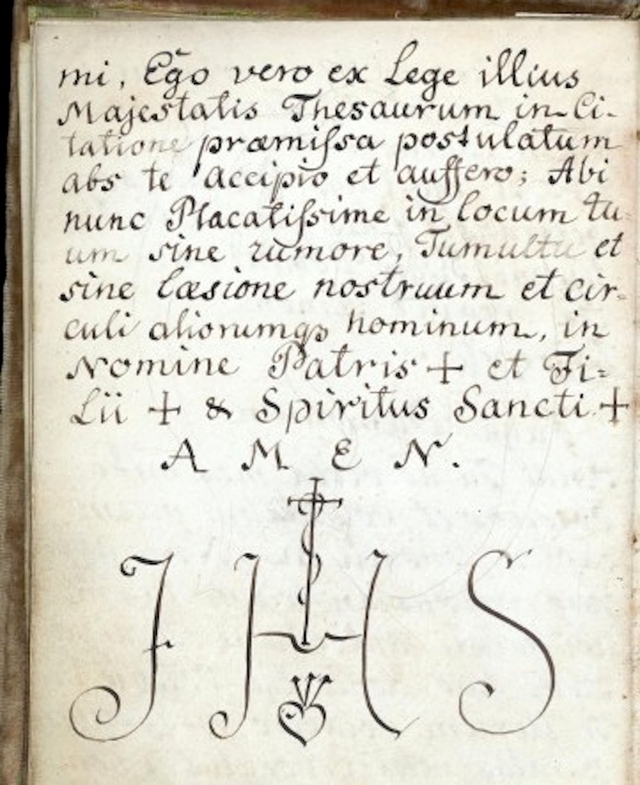

Today they circulate still, buoyed by the more sophisticated global networks of the internet. Since this post is an invocation of these spells, of a sort, I thought I’d end with the final page of the book, and a rough translation which shows it to be a magical command to a summoned creature to return from whence it came.

“I truly, from the law of that Majesty, do receive and take the treasure requested by you in the sent proclamation. Go away now most calmly to your place, without murmur and commotion, and without harm to us and to the circle of other men. In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, AMEN.”

You can browse high resolution scans of the complete book at Wellcome Images.

February 1 update:

Thought I’d add a translation note from a reader, plus this new image from the manuscript which garnered one of my favorite responses to an Appendix post to date:

@appendixjournal @craftyhanna There. Now mine matches. pic.twitter.com/on9oLss5UV

— + = (@sumares) February 1, 2014And in regards to the golden image featuring Hebrew writing above, many thanks to David S for emailing me with this information:

The top right arc of the circle says “Eloheynu” which means roughly “Our God.” The top left says “Echad” (ch sound as in chutzpah, chanukah) meaning “one.” I’m unsure of the bottom word, but it would be pronounced like A-ra-ree-hah, or A-ra-ray-hah, though the vowel sounds could be different. The center triangle has the word for god that in english is “Yahweh.” the letters are Yud, Hay, Vav, Hey, which would be pronounced “Yahvah” or “yahava” but is never pronounced this way It’s a common word for God in the Torah.

Thanks to all who have read the piece, and please do get in touch with me if you have any further information to share!