Hans Baldung, “Witches Sabbath,” woodcut circa 1510.

Hans Baldung, “Witches Sabbath,” woodcut circa 1510.

Bespelled in the Archives

I grimaced, examining the neat box of pale blue cardboard in front of me. Manuscript number 4171? This wasn’t the one I’d ordered, and I was conscious of my rapidly passing research week. With only a couple hours left until the library closed, I wouldn’t be able to order the correct manuscript before the next day. I shrugged, deciding that it was a sign—take a quick look, leave early.

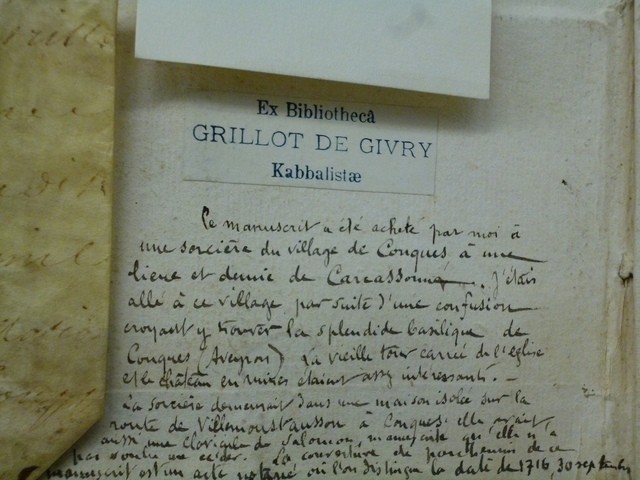

The manuscript seemed unusual, even as I opened the small box to unwrap the book’s protective layer of thick, creamy archival paper. Not much larger than a slim paperback, it was bound inside a recycled French legal document from 1716: smooth, stiff vellum with faded writing, its front cover marred by a burn from some long-ago stray cinder. The title was intriguing: Recueille de diferents secrets (“Collection of Different Secrets”). The real treat, though, was on the inner leaf. Two book plates indicated that the manuscript had been owned by the famous occult historian, Émile Grillot de Givry “Kabbaliste” (1874-1929), who had written a short account of its acquisition. Grillot de Givry’s own discovery of the manuscript had been as serendipitous as mine.

Le manuscript a été acheté par moi à

une sorcière du village de Conques à une

lieue et demie de Carcassonne. J’étais

allé à ce village par suite d’une confusion

croyant y trouver la splendide basilique de

Conques (Aveyron). La vielle tour carrée de l’eglise

et le château en ruines étaient assez intéressants.

La sorcière demeurait dans une maison isolée sur la

route de Villemoust aussou à Conques. Elle avait

aussi une Clavicule de Salomon, manuscrite qu’elle n’a

pas voulu me céder. La couverture de parchemin de ce

manuscrit est un acte notarié où l’on distingua la date de 1716, 30 septembre.

The manuscript was bought by me from

a witch in the village of Conques a

league and a half from Carcasonne. I had

gone to this village due to a confusion

believing I’d find there the splendid basilica of

Conques (Aveyron). The old square tower of the church

and the chateau in ruins were interesting enough.

The witch lived in an isolated house on the

route between Villemoust and Conques. She also

had a Key of Solomon, a manuscript that she did not

want to let me have. The parchment cover of this

manuscript is a notarial act in which one makes out the date of 1716, 30 September.

“The manuscript was bought by me from a witch in the village of Conques.” Émile Grillot de Givry’s account of how he came to possess WMS 4171. Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London. Photograph by the author.

A witch. A kabbalist. A magic book.

I was hooked.

Flicking through the pages, I spotted recipes and charms to find lost objects, cure nosebleeds, prevent animals from eating, hold snakes, and—of course—make someone love you. But there was so little time.

What had intrigued me most, as I sped through the fragile pages, was the slippage between magic and religion in the manuscript.

The eighteenth century is often studied as part of ‘the Enlightenment,’ treated as a period when people moved away from ‘superstition’ (as Enlightenment thinkers would have disparagingly termed it) to rationalism. The Catholic Church, which was aware of the overlap between religion and magic, had long been concerned with magical practices that involved divination or invoking demons. Historian Keith Thomas, for example, suggested that the shift started during the Reformation when the power of sacraments such as the Eucharist was dismissed by Protestants.

The true extent of change is questionable; Stephen Wilson has shown that many European magical beliefs persisted through the nineteenth century. That the educated elites and the general populace developed an increasingly different worldview is clear, though. Or at least that is what the educated elites were determined to believe. An educated physician and a cunning-man—a folk healer—had more in common than either would have liked to admit. In the mid-eighteenth century, for example, physician Vivant-Augustin Ganiare observed epidemics and weather closely to uncover God’s secrets. Ganiare believed that God had left patterns in nature for man to discover, which would provide man with solutions for controlling disease.

This was not entirely different from a peasant who used secret charms (often religious) to protect his cattle from disease and crops from withering. At the same time as the study of natural philosophy became popular among the French educated elite, those lower down the social scale were purchasing the cheap almanacs, magic books and hagiographies sold by pedlars (the Bibliothèque Bleue). Learned natural philosophy and popular magic each tried to explain and to manipulate the natural world.

Years later, when I finally returned to this curious manuscript, I had become more intrigued than ever by the ambiguities of the Enlightenment. The manuscript beckoned. Now, I had more time and, armed with Twitter and Storify, was able to share my delight and disgust in equal measures as I tried to understand the little book and its magical recipes.

A secret to repel snakes advised throwing a blank piece of paper (folded into four) at the snake, while saying “Stop yourself, beast! Here is a forfeit!” and “ozi, ozia, ozi.”

Secret pour arretter les serpens

il faut prendre un morceau de papier Blanc quil

faut ployer en quatre en disant arrette toi

Bette voila un Gage vous lui jetteres en prononçant

Les dittes parolles on dit de plus – ozi –ozia –ozi.

These were heavy demands. Few people carry a blank piece of paper with them, let alone are able to fold it quickly and throw it in the length of time it takes a snake to get close. The rationale, at least in part, was clear—the snake was being offered a substitute victim.

The boundary between magic and religion was permeable in pre-modern Europe, which might also explain the charm. The number four might suggest the points of the cross, the transliteration of the Hebrew name for God (YHWH), the Biblical gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John), or the elements (earth, water, wind and fire). There are religious hints as well in the “Ozi-ozia-ozi”, which perhaps was derived from the name of a Biblical king, Uzziah (Latin: Ozias). A powerful ruler, Uzziah designed wall-defences to shoot arrows and hurl stones—hence the thrown paper—but his pride led to a fall, rather like Satan (represented by the snake). This seemingly religion-free recipe only makes sense when considered within a religious context.

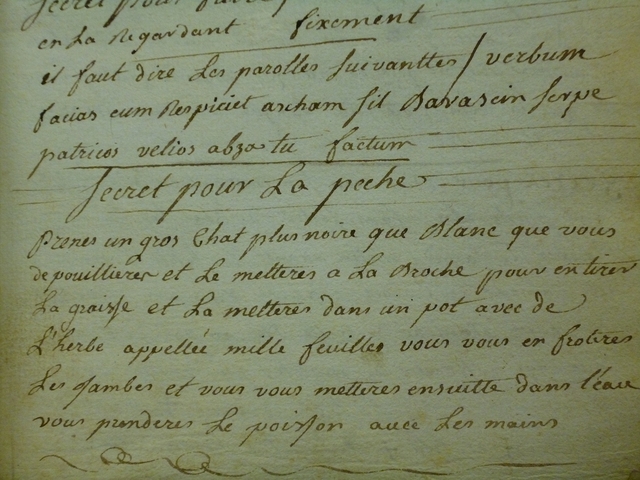

Not all spells were religious: many overlapped with medical ideas. To be successful at catching fish, for example, one recipe recommended that the reader “take a large cat, more black than white, skin it and put it on the roasting spit.” Mix the fat drippings with some yarrow, then “rub your legs and go next into the water. You will catch the fish with your hands.”

Secret pour la Peche

Prenes un gros chat plus noire que blanc que vous

de pouillieres et le metteres a la Broche pour en tires

La graisse et la metteres dans un pot avec de

L’herbe appellée mille feuilles vous vous en froteres

Les jambes et vous vous metteres ensuitte dans l’eau

vous prenderes le poisson avec les mains.

The manuscript’s ‘secret for fishing’ involved doing unwholesome things to “a large cat, more black than white.” Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London. Photograph by the author.

The use of animal parts—including those of puppies, kittens, and other cute creatures—was not unusual in early modern medicine. Indeed, there was much overlap between magical and medicinal properties. Within the wider worldview, every person and object was a balance of hot, cold, wet and dry properties. Puppies at once represented youth, warmth and moistness and so would be good for, say, diseases of age, which were cold and dry. Magic extended the possibility of transference even further. The logic of the spell for fishing was that the cat’s skill in catching fish could be directly transferred to the human.

The Recueille reflects a close relationship between magic, medicine and religion, but to get a sense of it as a whole, I counted and categorised the entries. There are 169 entries, sixty-seven (40%) of which are about medicine or medicinal ingredients. Forty (24%) aim to control people in some way, from making them fall in love to stopping enemies. Another thirty-seven (22%) focused on controlling nature, such as talking to the animals or summoning birds. Only five entries included divinatory or spirit-summoning activities. The remainder dealt with:

• luck (winning the lottery, escaping from prison or finding lost objects);

• weapons (avoiding injury from firearms and swords);

• mind or body (improving memory, seeing the invisible, or reading in the dark).

The charms in the manuscript—narratives, images and symbols—are similar to much older ones, as well as to others from the eighteenth century that appeared in printed books.

The book was intended to be useful on a daily basis rather than for arcane or demonic knowledge, allowing glimpses into eighteenth-century rural life. The concerns revealed are unsurprising, as magic was an attempt to control the uncontrollable. Keeping foxes and wolves away. Removing the pain of teething children. Preventing chimney and field fires. Staying safe from thunder and lightning. Ensuring pregnancy. Making someone fall in love. More surprising, though, were ten spells to avoid being harmed by weapons and one to escape recruitment by ballot for the militia. The countryside had its human dangers, too.

Secret pour empecher de tomber a la milice

Lorsquil sera question d’aller tire au sort pour la

Milice il faut Lorsque Lon vous appellera a

votre tour marcher a grand pas et etant arrivée

au Chapeau ou autre chose dans Le quel feront

Les Billiets profers les parolles suivants tout

Bas en tirant dans le Chapeau, et en faissant

un signe de Croix ╋ avec le d[oig]it index en disant)

Jesus passant par le milieu deux son alloit) et

Consumation est.

Secret for preventing [one from] falling to the militia

If there is the question of going to draw lots for the

Militia, it is necessary that when your turn is called,

you walk with large steps and, having arrived

at the hat or other thing in which the tickets are,

utter in a whisper, holding it in the hat and making

the sign of the Cross ╋ with the index finger, saying

(Jesus passing by the middle two his success) and

it is fulfilled.

The most poignant entries were to restore domestic harmony. To make a drunk hate wine, for example, one might mix eels in a vat of wine, later giving the drunk a glass. A charm “to maintain the peace in a house between husband and wife or other person” involved saying Latin fragments of prayer: “peace of our Lord Jesus Christ, between us through the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.”

Another compared anger within the household to a betrayal. When someone in the household or family was “in a bad humour or choler against you, it is necessary to whisper the following words, ‘Oh man appease your fury and your heat, as Judas lost his colour when betraying our Lord. The word became flesh.’”

The charm also suggests an early modern way of understanding anger: as much physical as emotional, and something that undermined family stability. Reading these charms, though, I could only imagine how bad a situation must have been for a person to look for magical assistance in restoring household peace. The willingness to use protective magic suggests that the threat posed to domestic stability by family disharmony was significant indeed.

These examples suggest that magic did not exist in opposition to religious faith, but relied on it. At one point, the author even stressed the importance of making confession within a day of one spell designed to prevent fire. The charm, which was “very dangerous for the soul”, involved drawing a cross and writing one’s baptismal name in blood taken from the right little finger. Religious belief—mingled with these ‘superstitions’—offered a meaningful framework for modelling relationships, understanding the natural world, and solving problems.

It is difficult to know why these charms were written down, or by whom. The manuscript is written in one legible hand and is in generally good French, which suggests the author had some education. At least part of the book was copied from a famous magic book, the Enchiridion Leonis Papae, as a note indicates: “fin des secrets de l’Enchiridion”. There is also the possibility that, for some of the text, the author had collected local folk knowledge out of interest. The author did not always take the charms seriously. The secret for understanding the language of animals included going into the forest at the end of autumn, then cooking the first animal and bird that had been killed in a stew seasoned with fox heart. After eating the stew, “you can persuade yourself that this secret will be good.” A strange choice of words.

Other remedies suggest a form of counseling. In a charm to know whether or not a wife was faithful, a husband might put a fine diamond under her pillow while she slept. The unfaithful wife would wake up frightened, but a wise wife “will kiss him lovingly.” To know the name of the seducer, the husband should “take the heart of a turtle and the head of a frog,” dried and pulverised, and throw the powder on his sleeping wife’s stomach. While sleep-talking, his wife would reveal “what he wants to know, or rather what he might like to ignore it for his own happiness.” Excellent advice. As Keith Thomas suggested, many such spells relied on a practitioner’s knowledge of the people involved. An observant wife, innocent or guilty, was already likely aware of her husband’s suspicions, while a wise husband might consider more deeply his need to know at all emotional and financial costs.

There are some hints that WMS 4171 may have been a working book. The burn on its cover evokes an image of someone leaving it near the hearth fire or a candle, perhaps after reading it. The Recueille was typical of other contemporary recipe collections with its emphasis on remedies. Although the recipes do not appear to be organised, the list of medicinal materials and their properties forms a significant and coherent section in the middle of the manuscript. This would have been useful for quick reference. Writing down the recipes in a personal book, particularly those from the Enchiridion, might even have heightened their power for the user.

Two charms even specified that they have been “proved,” which meant that they had been tried and found good. One was a secret to stop a field fire. Another aimed to persuade people to disarm, cautioning that it should not be tried when people were drinking. The first one entailed whispering a series of prayers, some in Latin and each in multiples of three, into the burning fire. The instructions began, “it is necessary to say the following words 3 times 3: Blessed St. John hear my request. Accord me, I beg you, the power to stop this fire by my breath.” After saying the Benediction three times, “blow the fire three times.” The rest of the prayers could be undertaken from a safe distance “without any dangers.” This one included an important number, a saint and the breath of life—and was practical, too, allowing the charmer to do work from a safe distance.

The second charm required collecting the white skin from the tongue of a newborn on a clean piece of paper or linen, which was then secretly placed under the infant’s bonnet during baptism. Bodily secretions and human body parts were regular components in both medicine and magic, such as feces to treat eye problems, human skull incorporated in epilepsy remedies, or the “hand of glory” (a preserved hand from an executed man) to unlock doors magically. The charm for putting down weapons would have worked on multiple levels, with the newborn representing the liminal states of new life, baptism and innocence, as well as literally embodying a Biblical verse: “out of the mouths of babes and sucklings” (Matthew 21:16). The tongue, with its ability to curse or bless, was considered a potent body part. A strong charm, indeed, bringing together body and soul, magic and religion.

Neither of the approved charms was any less magical than the spells for talking to the animals or sleeping wives. Each blurred seemingly religious actions with magical enhancements: a focus on specific numbers or a devious method of obtaining a sacramental blessing. If the book was being used, it was being used for its magic as well as its remedies.

For the historian, decoding the underlying rationale of the individual secrets is the easy part. Making sense out of a text and trying to identify its use without the details of its original context is a challenging business. The manuscript does not yield its own secrets readily.

And so we return to Grillot de Givry and the mysterious sorcière. Just as the manuscript gives little away, so too does Grillot de Givry. How did he know the woman was a witch? Or did he simply assume it because she had magical books in her possession and lived in an isolated house? And why did she refuse to sell the Key of Solomon, a well-known magic book?

That she was so willing to part with the Recueille suggests that she didn’t find it useful, although Grillot de Givry, with ‘Kabbaliste’ so proudly emblazoned after his name, clearly anticipated it might be. If the woman was a witch, the magic she practiced had moved on since the eighteenth century—even though the eighteenth-century practices had remained remarkably consistent from medieval ones. If she wasn’t a witch, perhaps her reluctance to sell the Key of Solomon was a failed ploy to persuade Grillot de Givry to raise his offer. She might have done better taking a chance with the old ways. Tucking a red swallow stone in her mouth during negotiations would, the manuscript assures us, have allowed her to obtain “anything that you ask of someone.”

In any case, Grillot de Givry left the village pleased with his purchase, and I left the archives, pleased with my day’s work. Both of us were grateful to the sorcière of Conques and her discarded spells.

Although in my case, I couldn’t help but wish that the manuscript included a charm to reveal the rest of its secrets.