While Darwin was writing his masterpiece, his children were drawing pink birds and carrot soldiers on it.

While Darwin was writing his masterpiece, his children were drawing pink birds and carrot soldiers on it.

Darwin’s Children Drew All Over the On The Origin of Species Manuscript (Updated)

Yesterday was Darwin Day, marking the 205th anniversary of the great naturalist’s birth on February 12, 1809. One of the great things about Darwin is that a huge amount of his work is digitized and freely available via sites like Darwin Online.

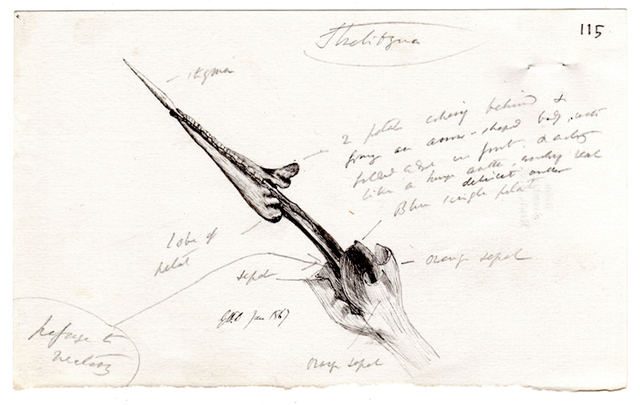

Interested browsers can also check out the Darwin Manuscripts Project, a collaborative initiative based at the American Museum of Natural History. Here you can read through Darwin’s personal notes, including gems like his scratched out book title ideas. There are also a number of nature drawings that Darwin prepared while writing his masterpiece, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859). Here, for example, is Darwin’s rather skillful drawing of the stamen of a Strelitizia flower:

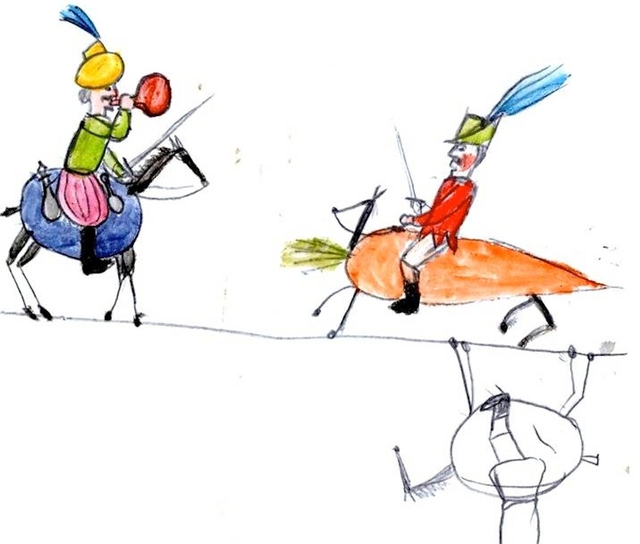

But there are other drawings in Darwin’s papers that defy explanation - until we remember that Darwin and his wife Emma (who, famously, was also his cousin) had a huge family of ten children. Scholars believe that a young Francis Darwin, the naturalist’s third oldest son, drew this on the back of Darwin’s manuscript for On the Origin of Species.

Remarkably, this is one of only twenty-eight pages of the manuscript that still exist. The Cambridge University Library has given it the descriptive name “The Battle of the Fruit and Vegetable Soldiers,” and so indeed it seems to be. As near as I can make out, it shows a turbaned soldier mounted on a blueberry squaring off with an English dragoon on a carrot-steed. Perhaps inspired by the 1839-1842 Anglo-Afghan War, and filtered through the Darwin household’s fascination with plants and gardening?

Here’s another drawing from the talented Darwin children, this one seemingly directly inspired by their father’s work. Birds are in the act of catching a spider and a gnat or bee, while flowers and a butterfly appear in remarkable detail. Clearly the family had a knack for acute observations of nature (in fact young Francis ended up becoming a naturalist as well).

This one’s my personal favorite: a child’s-eye view of the Darwin family home with cozy details like a tea kettle on the boil and a fluffy orange cat in the attic window.

Fascinatingly, this image might be detailed enough that it actually depicts Darwin’s famous sandwalk, his “thinking path” that led to the family greenhouse (which is, perhaps, the structure visible at the end of the path). The area was later made into a playground for the Darwin children.

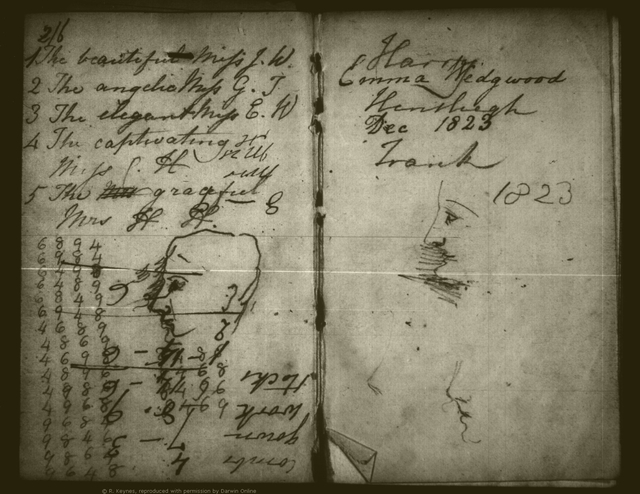

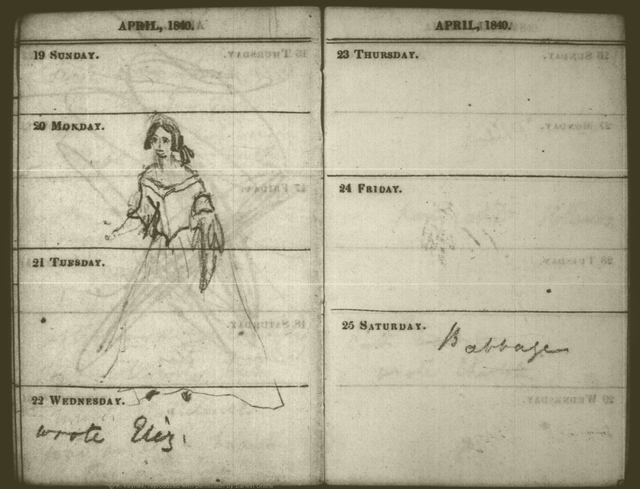

I poked around the items available at Darwin Online and came across Emma Darwin’s diaries, which are a fascinating resource. Emma seems to have been a talented sketch artist in her own right, doodling profiles and faces in over her daily schedule:

Here’s another, perhaps a self-portrait? Write us on Twitter or Facebook if you have any ideas as to whether this is Emma’s self-portrait or a drawing of another family member.

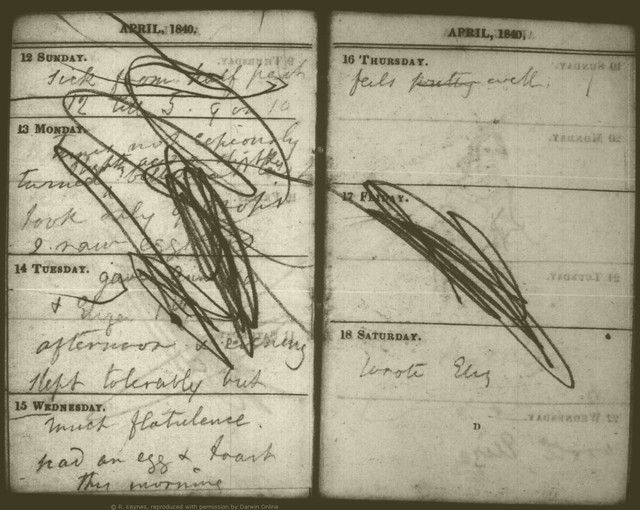

Amazingly, the Darwin kids even got into Emma’s diary, with several pages rendered unreadable by what is almost certainly a crazed toddler’s pencil. In fact, the back page of Emma’s potential self-portrait was defaced in precisely this way:

It’s all a great reminder that even legendary scientists had family lives, and that when we think about history, it’s important to remember that famous figures weren’t working in isolation. They were surrounded by far less famous friends, family members, acquaintances, and enemies. And sometimes, when we get lucky, we see some of their artifacts from the past too.

A tip of the hat, by the way, to Open Culture, a website that we’re avid fans of and which wrote the original post about the Darwin kids’ drawings that brought them to our attention. Also be sure to check out Darwin Online and the Darwin Manuscripts Project, two wonderful resources for anyone interested in the naturalist and his times.

Update:

I also wanted to include a short note on Annie Darwin, who died from tuberculosis at age ten and was Charles’ favorite child (or so he told his cousin). This box of items relating to Annie’s life that was collected by Emma Darwin offers another, sadder testimony to the tight-knit dynamic of the Darwin family, and to their artistic knack. Annie’s pink flowers in careful needlepoint seem to echo the exuberant nature drawings of her siblings:

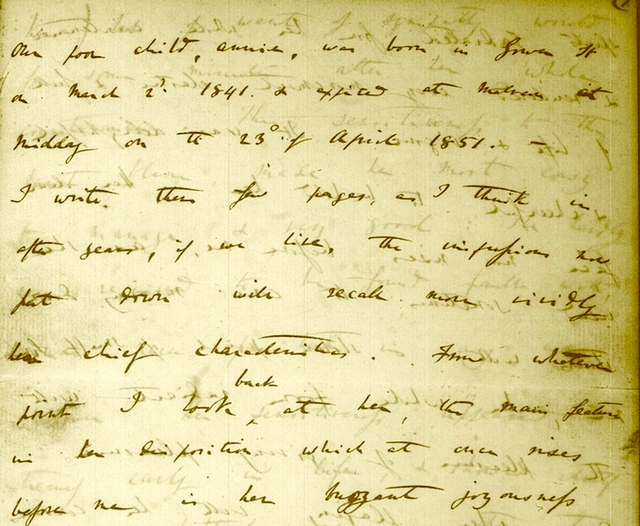

Darwin wrote about Annie after her death with touching earnestness as he tried to set down his memories of her before they faded:

Our poor child, Annie, was born in Gower St on March 2d. 1841. & expired at Malvern at1 Midday on the 23d. of April 1851.— I write these few pages, as I think in after years, if we live, the impressions now put down will recall more vividly her chief characteristics. From whatever point I look back at her, the main feature in her disposition which at once rises before me is her buoyant joyousness.

In his book Annie’s Box: Charles Darwin, His Daughter And Human Evolution, Randal Keynes argues that Darwin’s scientific thought was closely entangled with his family life, and that the death of Annie just before Easter in 1851 spelled the end of Darwin’s already weakening Christian faith. Students of the past are often leery of making overly explicit and binary links between work and life (I remember being amazed when I learned that Shakespeare’s son Hamnet died several years before he wrote Hamlet, and that literary scholars don’t make more hay with that fact). But if nothing else, it again reminds us that when historical figures become legendary icons, they lose much of the context that makes them human to us at the remove of decades or centuries.