A Much Too Distant Mirror: Against Animal Histories

A response to “The Meerkats Without History”—also featured in this issue of The Appendix.

“Am I not a fly like thee? Or art thou not a man like me?”

- William Blake

Back when I taught high school in West Virginia, I lived in a $400-per-month efficiency apartment near an abandoned post office on the banks of the Little Kanawha River. Mine was one of six units in the complex, a cross between a 1970s log cabin and a 1950s motor lodge, and renting it entitled me to the use of all the shared amenities: a great bird watching blind off the back porch, a free power washer for my Volkswagen, and—the pièce de résistance—a lukewarm jacuzzi beneath the grilling patio.

We also shared, in an informal and more or less involuntary sense, the monkeys. In a backstory too long and strange to go into here, our landlord had relinquished his ownership stake in a number of regional strip clubs, gone to prison for tax violations, and left his pet monkeys—a female white-faced (Cebus capucinus) and male tufted capuchin (C. apella)—in the care of his son, our super. In one version of the story that I later pieced together from my neighbors, the monkeys sometimes hung out in the clubs, traipsing around the light rigs and supplying all the ambience and sophistication of a rum commercial. By the time I moved in, they’d been forced into early retirement, and spent their days stalking back and forth through a long series of connected cages that ran through the garage and out around the hot tub. The female was sweet and quiet, usually too busy eating fruit to notice me, but the male was a constant nightmare of bared teeth and thrusting privates. He was loud, bawdy, and ready, if not downright eager, to bite my finger off. He was, and this is as gently I can put it, kind of a creepy dude.

All that was almost a decade ago, and even now I don’t remember that nameless primate sex offender with much fondness; in fact, I don’t think of him much at all. But reading an early draft of Ben Breen’s article in this issue of The Appendix got me thinking about the life that poor creature must have lived, the complete, impenetrable otherness of even our closest relatives, and what we really mean when we talk about “animal histories.”

Strip club monkey, if you’re still out there, this one’s for you.

First, some reductio ad absurdum. Do rocks have histories? I don’t mean in the geological sense, in which case the answer is clearly yes, but rather in Breen’s sense of history as a narrative arc played out by characters with their own motivations, hopes, and fears? Does the story of tectonic subduction have a protagonist? Are there tragic elements in the Rise and Fall of the Appalachian Mountains?

I would argue, and I suspect most would agree, that the answer is no. Rocks are historical objects in the sense that they change through time, and that those changes may or may not be reconstructed through hypothetico-deductive reasoning, but that doesn’t make them historical actors. To paraphrase an old rock song, they don’t show, they don’t share, they don’t need.

This distinction becomes less clear, however, when we put the same question to animal individuals. Rocks are hard to relate to, but furry creatures with soulful eyes and a familiar inner ear anatomy? Now the empathy comes easily: it doesn’t take much to look into their eyes and imagine ourselves. But do these acts of imagination get us closer to the truth? Or should we approach our instinctive empathy with caution?

The meerkat, Suricata suricatta: historical actor or historical object? Wikimedia Commons

Biologists who study behavior have been here before. The early twentieth-century movement toward a Darwinian ethology built itself up more or less in explicit opposition to this brand of overt anthropomorphism. This post-post-Cartesian shift was already underway when Conwy Lloyd Morgan set out his canonical rule, that “in no case is an animal activity to be interpreted as the outcome of a higher psychical faculty, if it can fairly be interpreted in terms of faculties which are lower in the psychological scale.” Sure, it may be true that honeybees worry about the oncoming winter and stock up accordingly, but it’s much more likely that simple changes in environmental cues trigger transcriptional cascades that in turn lead to changes in foraging behaviors. Since ghosts in the machine aren’t necessary to describe most animal behaviors, postulating them is usually neither science nor history, but something more akin to creative writing.

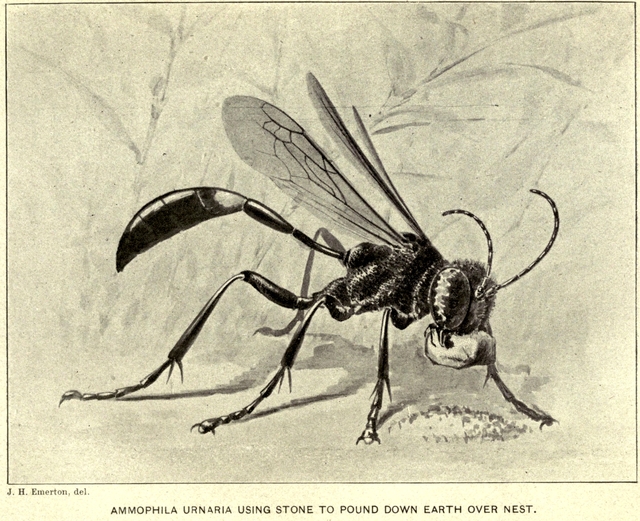

Even among biologists, this lesson took some time to sink in. One of the classic examples comes from my own field, entomology, where early researchers ascribed human-like intelligence to the digger wasp, Ammophila urnaria. Females of this species are solitary hunters who build nest tunnels in loose soil and feed their larvae on the caterpillars of moths and butterflies; in order to protect their nests from predators and parasites, the wasps fill the nest entrance with dirt, then tamp it in tight using a small pebble that they hold between their jaws. Imagine a wasp with a hammer, and you’re pretty much there.

The first widely read account of this “tool use” was published by the husband and wife team of George and Elizabeth Peckham in their 1892 book On the Instincts and Habits of the Solitary Wasps. To convey a sense of the tone, I have to quote the report at some length:

Just here must be told the story of one little wasp whose individuality stands out in our minds more distinctly than that of any of the others. We remember her as the most fastidious and perfect little worker of the whole season, so nice was she in her adaptation of means to ends, so busy and contented in her labor of love, and so pretty in her pride over her completed work … When at last, the filling was level with the ground, she brought a quantity of fine grains of dirt to the spot and picking up a small pebble in her mandibles, used it as a hammer in pounding them down with rapid strokes, thus making this spot as hard and firm as the surrounding surface. Before we could recover from our astonishment at this performance she had dropped her stone and was bringing more earth … in a moment we saw her pick up the pebble and again pound the earth into place with it, hammering now here and now there until all was level. Once more the whole process was repeated, and the little creature … intent only on doing her work and doing it well, gave one final, comprehensive glance around and flew away.

Thinking that they had observed a singular event—the extraordinary innovation of a tool by a particularly intelligent individual—the authors jumped to the extreme conclusion that Ammophila’s intellectual powers were comparable to, or even exceeded, those of the higher mammals. The idea proved so attractive that a figure from the text was widely reproduced in both biology and psychology textbooks throughout the first quarter of the 20th century, side by side with extended discussions of “wasp intelligence.”

Ammophila urnaria, thinking it over. From the Peckhams’ On the Instincts and Habits of the Solitary Wasps (1892). Internet Archive

And lest you suspect that the Peckhams were writing outside the bounds of the biological mainstream, here’s no less a personage than naturalist and essayist John Burroughs, waxing poetic in his introduction to the their later book, Wasps, Social and Solitary (1905):

[This volume] opens up a world of Lilliput right at our feet, wherein the little people amuse and delight us with their curious human foibles and whimsicalities, and surprise us with their intelligence and individuality … Such a queer little people as [the book] reveals to us, so whimsical, so fickle, so fussy, so forgetful, so wise and yet so foolish … verily a queer little people, with a lot of wild nature about them, and human nature, too.

This kind of thing is preposterous, of course. Wasp “brains” are about as far removed from our own as you can get and still be recognizable as a central nervous system, and subsequent studies of tool-use in wasps have put the old intelligence debate more or less to rest.

Still, the Peckhams’ almost manic brand of anthropomorphism lives on in nature docudramas like Meerkat Manor, March of the Penguins, or, most egregiously, any of the recent confections produced and distributed by the Disneynature label.

And that, of course, brings us back to Breen’s meerkats. Are they real protagonists? Or are we, like turn-of-the-century entomologists, just seeing what we want to see?

If ever individual animals had histories worth telling, surely those mismatched capuchins were worthy of a biopic. Born into captivity, sold into the pet trade at an early age, they ended up living inside a JT LeRoy short story, swinging from the rafters of a hillbilly gentlemen’s club while “Indian Outlaw” blared out across the PA system. We may be able to imagine the scene, but can we imagine their feelings?

The answer, unfortunately, is no, at least not honestly. While I suspect that most apes and monkeys share with us certain aspects of interiority, subjective experience, maybe even some form of hopes and dreams and fears, the differences between our species are very real, as any serious primatologist will tell you; while these animals may have “souls” of a sort, they must be of a distinctly different flavor than ours. To ascribe our own motivations, our own interior feelings—our stories of revenge and passion and purpose—to primates with different brains and different evolutionary histories is a supremely hubristic thing to do. And if we can’t really know our closest relatives, how can we expect to relate to meerkats, separated from us by more than 75 million years of divergent evolution?

So where do we go from here? Are the only animal histories worth talking about the kind evolutionary biologists study, histories that treat individual animals, their genomes, and their characteristics the way we treat rocks, as mere historical objects? These will never be the stories of plucky individuals beating the Darwinian odds, of Shakespearean schemers at loose on the African plains. Instead, they’re absurdist tales of rising mountains and crumbling species groups, of lineages doomed, of gene motifs that carry on, tangling and duplicating across billions of blind generations. And their defining characteristic, the source of their simultaneous attraction and repulsion? Their sheer, discomfiting inhumanity.

Absurdist tales of lineages doomed: An approximately 99-million-year-old extinct ant species (Zigrasimecia tonsora), trapped in amber. Depressing stories like these are nature’s specialty. Phillip Barden/Antweb.org

I sometimes think of the historical sciences—geology, evolutionary biology, certain branches of astrophysics—as analogous to trying to reconstruct a complicated “night before” with a drunk in a bar. In this case, nature’s the drunk: It knows what happened, but it’s sure as hell not going to give it to you straight. The big difference is that you can at least relate to a drunk. Nature is a dark narrator, an artist of indifference, Cormac McCarthy on a cosmic scale. When the stories it tells don’t fit easily onto a narrative storyboard, we force them, willfully blind to inconvenient truths about our fellow animals, their nature, their mysteries.

Please do keep that in mind if Disneynature decides to make a film about digger wasps and the challenges of being a single mother.

That this Hobbesian universe gave rise to humans—troubled, but well-meaning children desperate for a bedtime story—may not be a miracle, but it’s still a remarkable thing. It may well be the case that language, narrative, and imagination are our major evolutionary discoveries. If so, then what a strange gift: eyes to see, voices to speak, and souls to hear the stories of our species.

At the end of the day, shows like Meerkat Manor or March of the Penguins are delightful, but they’re also a trap. They promise us a connection, but give us no more hint of their subjects’ interior lives than The Jersey Shore did for JWoww, Ronnie, or Snookie. Clever editing may cover a multitude of sins, but it’s not a gateway to empirical knowledge, and as often as not it’s downright disrespectful, both to the animals and to the scientists who study them. While I don’t think Breen is advocating that we take those shows seriously, I’m not sure I see how any “animal history” can escape their fundamental flaw: the projection of our own personalities onto the unknowable animal mind. What is it like to be a meerkat? I’m afraid I have to side with Montaigne on this one.

Que sais-je?