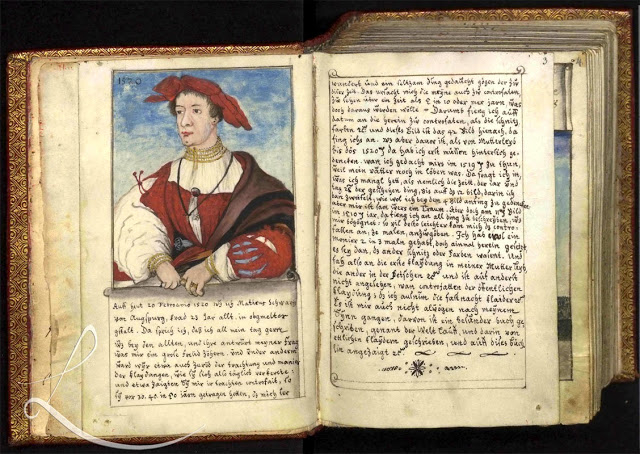

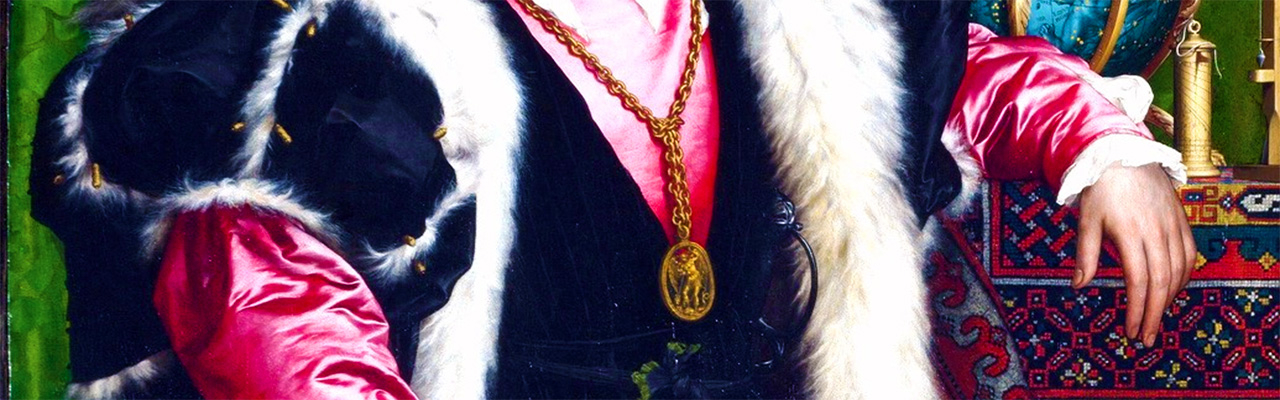

For the haute bourgeoisie of sixteenth-century Europe, bodily adornment was a route to worldly success. (Detail from The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein, 1533)

For the haute bourgeoisie of sixteenth-century Europe, bodily adornment was a route to worldly success. (Detail from The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein, 1533)

Did the Renaissance Invent Fashion?

Fashion, the historian Ulinka Rublack has suggested, is a manifestation of modernity. Although humans have always expressed themselves through personal adornment, the contemporary sense of fashion as a changing set of styles which fall out of vogue on a yearly basis had to be invented. And one of the people who helped invent it was an otherwise unexceptional sixteenth-century German accountant named Matthäus Schwarz.

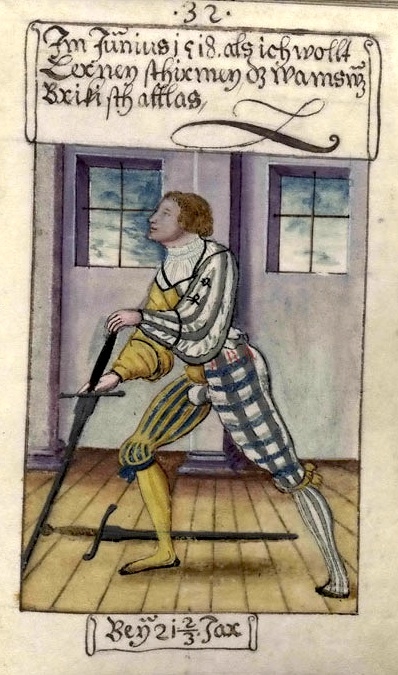

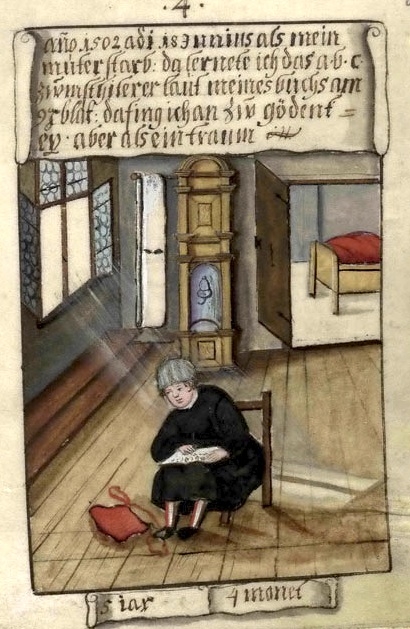

The images below are from a remarkable book of portraits that Schwarz (1497-1574) commissioned of himself at various ages and stages of life. I hesitate to call them selfies, exactly, but they do capture the exhibitionist nature of the form: Schwarz’s Trachtenbuch (Book of Clothes) was clearly designed for display, and on the whole it paints him in a good light—aside from a rather unflattering nude portrait of his paunchy late twenties. The book is an act of what Stephen Greenblatt has called “Renaissance self-fashioning”: it announces Schwarz as a person of taste, a supporter of his city and family, a courtly lover, and a well-rounded Renaissance man. It is also, arguably, one of the first fashion books, a distant progenitor of a Vogue lookbook, as it were.

This week marks the end of the Appendixl’s sixth issue, “Bodies,” and in the past three months we’ve covered a lot of ground in the realm of the human form, from Lincoln’s quasi-beard to Tipu’s tiger. But we haven’t done much on fashion and its history, and I wanted to remedy that with this post. We can debate to what degree these paintings are early manifestations of a distinctly modern ethos or simply a reflection of the abiding narcissism and love for self-display of all human beings (on this, see more below). But I think we can agree that they’re a remarkable testimony of a life in clothes.

A bit more about Schwarz and his remarkable book, the early pages of which you can read above. Schwarz, a resident of the German Imperial Free City of Augsburg, was an employee of the powerful Fugger banking dynasty, and as his wealth grew in his late twenties he began to commission a series of illustrations from local Augsburg painters. In these images we see a man’s life play out as if in a film: the infant of the early paintings grows to become a proud 15-year-old riding a horse, then a young man wearing elaborate Italian suits of red silk. When his employer Anton Fugger is married we see Schwarz as a handsome man of thirty attending the wedding in rich velvet with a dueling sword at his side; when Fugger dies, Schwarz is a sixty-three year old wearing black robes and a wintry white beard. These aren’t just images of fashion: they’re a life in miniature.

##Age One

Schwarz as a new-born infant. Note the five-pointed star on his cradle: perhaps a charm against evil? Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Five

At age five, Schwarz is learning the alphabet and mourning the death of his mother. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Eight

Schwarz rides in the back of a wagon at eight and a half years old. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Nine

Hawking in the countryside with a friend, nine years and four months old. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

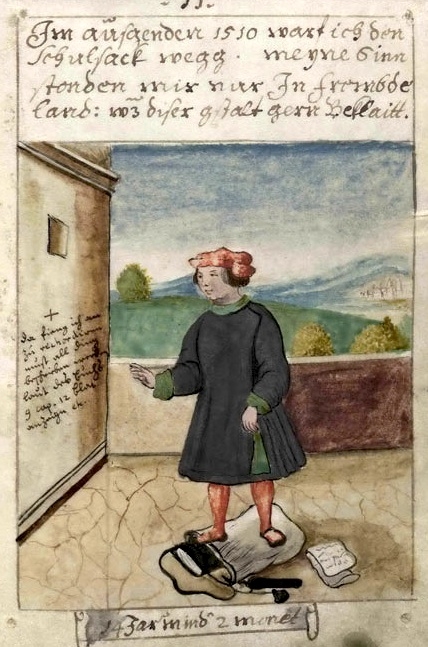

##Age Fourteen

Schwarz trampling on his schoolbooks as a rambunctious fourteen-year-old. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Fifteen

##Age Nineteen

Hawking at nineteen and seven months in a fashionable suit with codpiece, sword at side Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

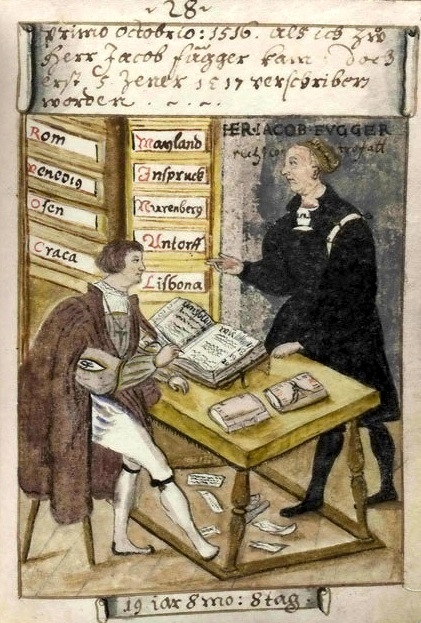

##Age Nineteen

A month later, working as a clerk to Jakob Fugger, one of the richest men of his era. This is the most interesting painting in the book to me, offering a peek into the world of high finance during the Renaissance. Note the pouches on the wall filled with letters to (or from?) major cities like Rome and Lisbon. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Twenty-One

##Age Twenty-Two

At an archery contest at twenty-two years of age, wearing a similar suit and a foppish ruffled hat. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

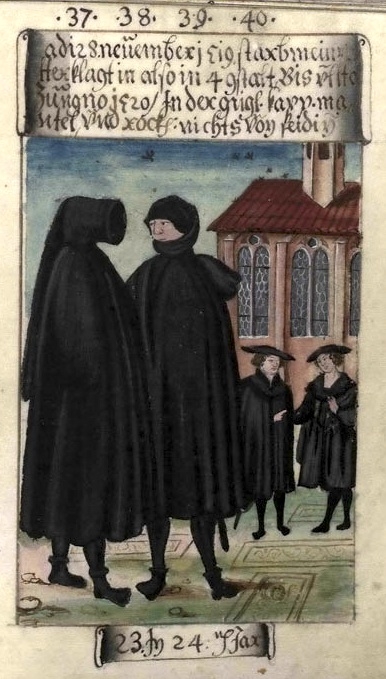

##Age Twenty-Three

A fop no more: Matthäus mourns the death of his father. All four figures in this picture depict Schwarz wearing different varieties of mourning dress. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Twenty-Six

This is a particular favorite of mine. Here Schwarz is a businessman of twenty-six visiting Nuremburg, and looking a little put out by the stray dog peeing at his right! Note the money-sacks at his belt and the fashionable cloak with arm holes. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

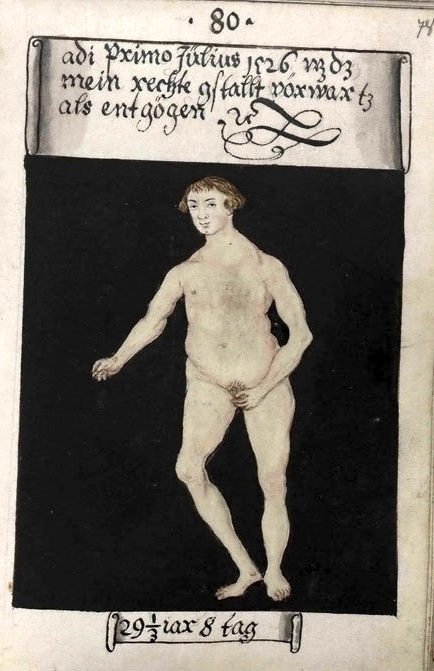

##Age Twenty-Nine

Stark naked at twenty-nine. Schwarz noted in relation to this picture, "I had become fat and large." Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Twenty-Nine

Wearing plate armor and bearing halberd in preparation for the attack of Emperor Charles V, age forty-six. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

##Age Forty-Eight

Now middle-aged and bearded at forty-eight, Schwarz walks with his squire (and perhaps son?) Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

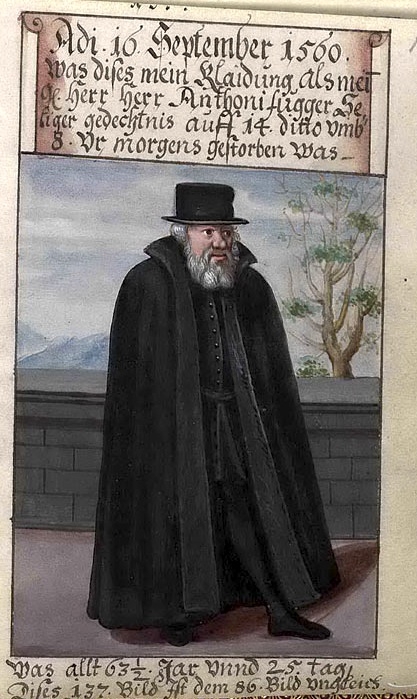

#Age Sixty-Three

The final portrait of Schwarz in the album. Wearing formal black in the “Spanish style” that would later evolve into the modern business suit, suffering the effects of a stroke, a sixty-three-year-old Schwarz attends the funeral of his employer, Jacob Fugger. Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig

You can look through a digitized version of the full book here—what I’ve selected above is just a sampling of the images on offer. But for those looking for some context, I can’t recommend Ulinka Rublack’s Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe highly enough. It’s simply the best book about fashion, and one of the best works of early modern history, that I’ve ever read.

Rublack’s strength is to contextualize fashion in a very big picture. She sees the frenzied style-chasing of merchants like Schwarz as part of a far larger movement toward mass consumption and mass production of luxury goods in the early modern period. During the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a new world of goods became available to an ever-broadening segment of the earth’s population. In both early modern Europe and in Ming China and Tokugawa era Japan, goods like silk textiles, prints, fine furniture and medicinal drugs became available to ordinary tradesmen and craftspeople.

The rise of urbanization (led by Edo, the city which would become Tokyo, which reached one million inhabitants by the early 18th century) made it possible for merchants to set up lavish shops catering to the shifting tastes of an emerging urban middle class: glovers, goldsmiths, perfumers, dyers, druggists, shoemakers, drapers, and costumers. The common thread connecting these trades, and the people who consumed them, was the body. Altering bodily states, whether by consuming an exotic drug like opium tincture or powdered mummy, or by adorning oneself with costly silks and jewels, was central to the rise of modern capitalism as we know it. As Rublack points out, moreover, clothing was actually a form of monetary exchange in the early modern world: “textiles stored value far more effectively” than coins, she writes, and they offered an economic outlet for women of means to retain their wealth even after marriage: “marriage contracts stipulated that clothes and jewelry were a woman’s ‘inalienable’ possession.” And global trade routes relied on ever-changing demand for new textile patterns and clothing styles to sustain them. East India Company merchants in Bombay worried about the fashions of lady’s dresses in London precisely because they knew that clothing styles helped make their long-distance trade possible.

Fashionable clothes, in other words, might not simply have been a manifestation of an emerging modern world. They might have helped create it.