Robot of Jihad? A Guide to Tipu’s Tiger

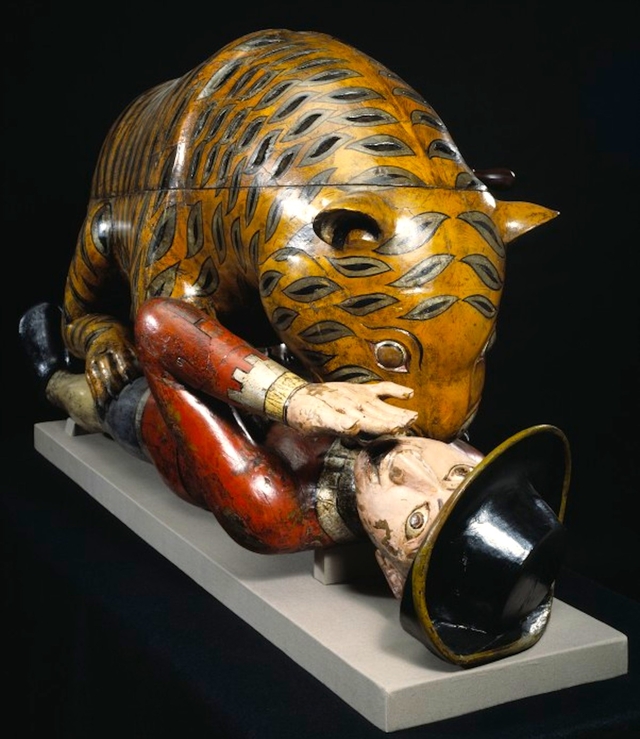

An eighteenth-century automaton in the image of a tiger mauling a British soldier, whose groans mingle with his killer’s roar, has thrilled millions of tourists and inspired some of the English language’s finest poets. It is one of the British Empire’s most celebrated prizes, stolen in 1799 from the court of Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore. Over the previous half-century, Tipu and his father Haider Ali had repeatedly trounced British armies and flaunted ties to France, Britain’s rival superpower. Although France refused to grant Mysore a formal alliance, it filled the Mysorean capital of Srirangapatnam with European mercenaries, artisans, and mechanics, some of whom seem to have contributed to the creation of the machine now known as Tipu’s Tiger.

From his rise to power in 1783, and even after his death beneath the walls of his citadel in 1799, Tipu was an iconic figure in Europe, parodied or glorified in cartoons, paintings, and a forged set of memoirs. In South Asia, however, he was the master of his own celebrity. Tipu stamped nearly every conceivable sort of object with the features of his reign’s symbol: the tiger. No other rulers in the Subcontinent represented their authority with such flamboyance and insistence. A mechanical man-eating tiger was only the most astonishing example of Tipu’s commitment to his brand.

Now Tipu’s Tiger is a brand in its own right, with all of the YouTube clips and apps requisite of modern celebrity. An anchor of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, it attracts crowds and the attention of scholars from diverse fields. But however seen and studied, the Tiger remains mysterious. Unlike the countless tiger-headed or tiger-striped swords, guns, and thrones of Tipu’s palace, the Tiger bears no inscription. Its pedestal, if it had one, was left behind by British looters, perhaps not valuable or not light enough to be taken.

Little written evidence exists to suggest where the Tiger might have been placed originally, how it might have been used, or why it was built. Did it stand in one of Tipu’s private chambers, to amuse the sultan? In an entrance hall, to amaze dignitaries? Or in a storage room, to await its destiny? No one knows—which hasn’t kept anyone from speculating. For two centuries, Western writers have guessed the meaning of the spectacular machine. Their answers reveal less about the Tiger than about the persistence of Orientalist clichés and Islamophobia from the Victorian era to our own.

Despite the variety of personalities weighing in, from poets to art historians, two interpretations of the Tiger have predominated. The first holds that it was a monstrous device dreamed up by a tyrannous madman; the second, that it was the plaything of an obsessional man-child. For variety, the two interpretations are sometimes combined.

The earliest British observers maintained that Tipu’s Tiger was a vicious simulacrum capable of entertaining only a depraved and cruel mind. Colonel Mark Wood, co-author of an 1800 book on the British defeat of Tipu Sultan the year prior, described the Tiger as a “characteristic emblem of the ferocious animosity of Tippoo.”

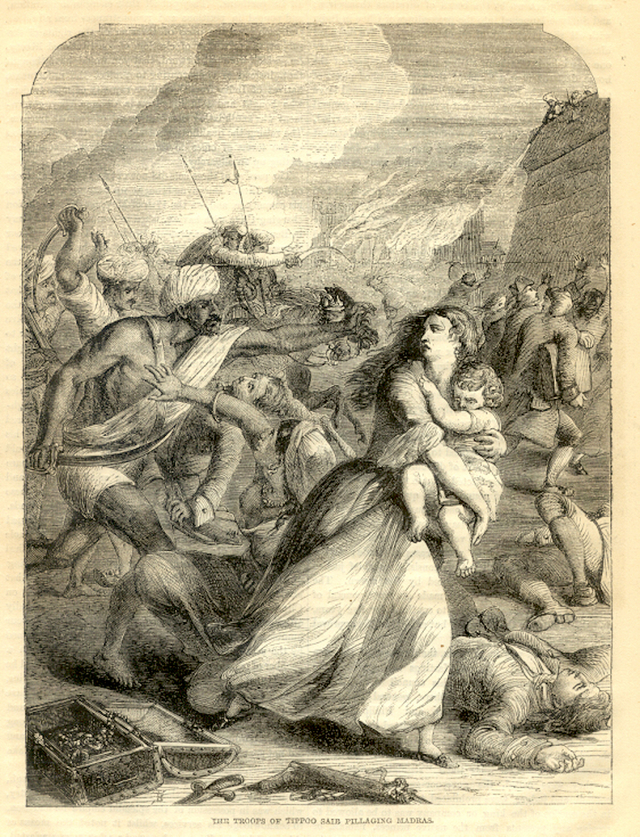

Mark Wood’s story, a hit in its own day, haunts contemporary perspectives on the Tiger. Wikimedia Commons

Wood was referring to Tipu’s notorious treatment of his British prisoners of war. Hundreds of British soldiers had been captured by Mysorean forces during the Second Anglo-Mysore War (1780-1784). Tipu kept them imprisoned in the dungeons of Srirangapatnam for years longer than originally stipulated, and subjected them to humiliating and excruciating circumcisions. Circumcision was rare in Europe, and generally associated with ‘turning Turk’: conversion to Islam. Although Tipu, a pious Muslim, doesn’t seem to have had the forced conversion of his hostages in mind, his slighting of British manhood was interpreted as an act of sectarian as well as personal violence. Upon their return to Britain, a number of the former prisoners published widely-read accounts of their indignities, bolstering Tipu’s image as a depraved fanatic.

This image was a powerful weapon of British propaganda during the next wars against Mysore, which culminated in Tipu’s defeat and death in 1799. Colonel Wood’s reaction to Tipu’s Tiger was a symptom of Britain’s war-time vision of the machine’s former owner. Yet as the British came to love watching the Tiger themselves, commentators toned down their rhetoric about such amusement being fit only for bestial minds. The Tiger went on display in London’s East India House in 1808 (where it remained until its transfer to the V&A in 1879), and proved an immediate hit. The museum’s 1851 guidebook advanced the same thesis as Colonel Wood, but with a cool, light irony: “We may conceive” it sniffed, “how refined must have been the mind which designed such an invention.” No telling how refined must have been the British minds that crowded to see it. These delighted so much in hearing the machine’s roar that, twenty years later, they wore out the original handle.

As time passed and memories of the Anglo-Mysore Wars grew hazy, Western interpretations of the Tiger might have moved ever farther away from the views of Colonel Wood. Instead they have circled back.

Not that there isn’t fine, careful writing about the Tiger. In her 2009 book on tiger-imagery at Tipu’s court, for example, art historian Susan Stronge has contributed more than any single person to what we can objectively say about the device, proving it to be a variant of broader Indo-Iranian artistic and literary styles that identified kingship and heroism with big cats. She observes that most rulers used lions to represent themselves, and suggests that Tipu’s idiosyncratic choice of the tiger reflected a commitment to the Shia martyr Ali, who was often compared to tigers in Persian literature. In the midst of this, however, she proposes that the tiger motif expressed the sultan’s “constant preoccupation with jihad.”

But perhaps we are the ones preoccupied with it. The importance of Islam to Tipu’s reign continues to be debated, often viciously, in South Asian academia and popular culture. Certain Hindu fundamentalists and conservatives portray him as a Muslim bigot who does not deserve the reputation for anti-colonial nationalism he has been given in an influential strain of nationalist history-writing. Without a doubt, Tipu oppressed some native Christian and Hindu communities, which he suspected of collaborating with his British enemies. But ‘jihad’ is a poor, and politically dangerous, way to characterize his policies. He fought Muslim rulers like the Nizam of Hyderabad, and sought alliances with non-Muslim states such as France. He may have been ruthless, but he was hardly the archetypal Islamist war-monger of neo-con nightmares.

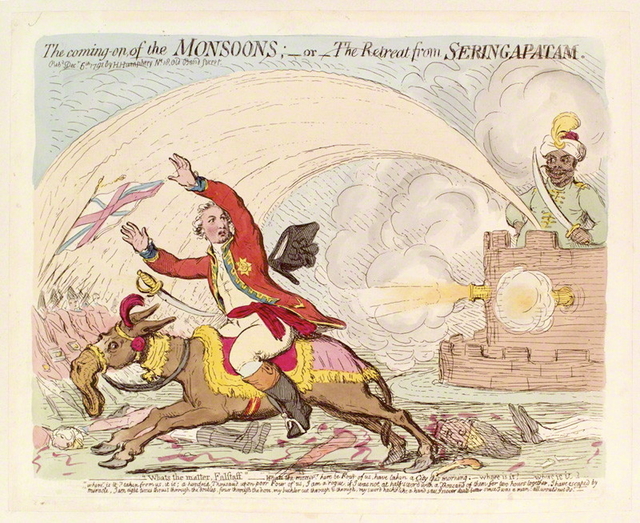

While Tipu was seen as a war-mongering fanatic, British violence in Mysore was portrayed as a laughing matter. Wikimedia Commons

Asking what kind of fanatical man created this machine, many observers forget to ask about the violent men who made it a museum piece. But others fail to see violence in the automaton at all, and find only a big toy made for Tipu’s entertainment. In an essay for a 1990 exhibition guide on the treasures of Tipu’s court, art historian Mildred Archer managed to call the Tiger a toy three times in two paragraphs, saying twice that Tipu must have loved playing with it. Literary figures have endorsed the toy-thesis as well. Marianne Moore anticipated Archer in her poem “Tippoo’s Tiger.” After several stanzas listing all the things Tipu owned printed with tiger stripes or capped with tigers’ feet, she came at last to the Tiger “a vast toy, a curious automaton.”

John Keats, who had seen the sultan’s automaton in person while working on his unfinished narrative poem “The Cap and Bells,” played the Tiger for laughs. He smuggled a description of it into his poem, calling the machine “a play-thing of the Emperor’s choice … a Man-Tiger-Organ, prettiest of his toys” and comparing its noise to a snore. This jocular reaction is perhaps preferable to seeing the tiger as a kind of mechanical mujahadeen—but if the tiger is a toy, what does that say about Tipu? He must have been, as scholar W. J. G. Ord-Hume puts it, a man with a “warped and almost childlike mentality.” Who else could have such a “pronounced and bizarre … preoccupation” with childish things?

Nor are the two interpretations really so far apart. Creative minds have always found ways to combine them. In his 1837 poem “Le joujou du Sultan” (The Sultan’s bauble) French writer Auguste Barbier managed to depict Tipu’s Tiger both as the amusement of an infantile tyrant and as a herald of jihad:

As day’s divine glimmer lit up the sky;

One of his servants cranked the machine

And the master, awoken, passed his eyes

Over the hellish plaything; its horrid noise

Relit his fury and raised up his hate

Against the conquerors of India.

Barbier’s portrait of Tipu is reflected even on the website of the Tiger’s current home, the Victoria and Albert Museum. In an extensive webpage devoted to its star attraction, the V&A claims that “the toy tiger” bears witness to “Tipu’s much publicized tiger-mania and anglophobia” (Tipu of course was ‘anglophobic’ in the sense that a man watching his house burn is afraid of fire). Rather than see Tipu as a rational sovereign trying, like his European counterparts, to remain in power and resist his enemies, the Museum treats Tipu as a fervent Muslim with serious psychological problems, evidence for which, it claims, can be found in his dream journal.

Tipu did indeed record a number of his dreams in a Persian-language diary, translated into English in 1957. But this record hardly reveals, as the V&A claims, “his preoccupation with tigers, and his association of the cult animal with the extermination, or at least the driving out, of infidels.” Tipu dreamed of tigers, but also of bears, cows, elephants, beryl, mangoes, dates, almonds, and plaintains—a treasury of things animal, vegetable, and mineral. He fantasized about defeating the British, but also about making peace with the Nizam and allying with French. His dream-self went on pilgrimage to Mecca and crushed the unbelievers, but also rebuilt a Hindu temple. As in waking life, the dreaming Tipu was a complex man too large for our clichés.