Welcome to Atlantis: The Solid Illusions of History

Matthew Gildner’s pithy article “Andean Atlantis” is a good example of what makes The Appendix both alluring and fun to think with. While I look forward to the more complex version of this piece in academic print, which will no doubt go far beyond these musings, the online format and the journal’s predilection for “narrative and experimental history” invites a more playful and immediate engagement, so here goes.

The April 2013 issue theme of “Illusions” is, it seems to me, by definition both unlimited and periodic. Since at least the eighteenth century one could say the same about “History.” What is not history? What is not illusion? The Holy Grail? The Eucharist? God? Babel? As historians, we can count on their unlimited iterations. Like the fictional character in “The Library of Babel” who traverses the seemingly endless labyrinth of the library of all possible knowledge, I am consoled by the ingenious Borgesian solution: that the extent and variety of the Library’s hexagonal halls is not “infinite” but instead “both unlimited and periodic,” that is to say, that the “number of possible books is limited” by the letters of the alphabet, and so the same volumes (let us, in an anthropological spirit, call the library a “museum” and its books, “artifacts”) repeat themselves in more or less the same chaotic disorder, which is to say, Order.

In this metahistorical faith in the order of the solidity of illusions I follow the equally fabled wisdom of Suárez Miranda, (fictional) author of the oft-cited “Del rigor en la ciencia” (Of Exactitude in Science) who reported (in the fictional mid-seventeenth century, remember) that

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied an entire City, and the map of the empire, all of a Province. With time, these Disproportionate Maps no longer satisfied and so the academies of Cartographers assembled a Map of the Empire that was the same size as the Empire, and that coincided punctually with that empire.

Of this map and its empire there remain “only tattered Ruins of the Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars.” These tatters are our future. And Tiawanaku is one of them. So is Bolivia or Peru or America or Atlantis, or, for that matter, any solid collection of alphabetic memories.

“Del rigor” is the first piece in the last part of Jorge Luis Borges’ prosaic El Hacedor (The Maker). Although the “Empire” here appears to reference “the Yellow Empire” of an imaginary China that appears elsewhere in the JLB opus, it may very well also invoke solid illusions of the all-encompassing precision of the Inca Empire, whose administrative grid once covered the landscape of the northern reaches of what is today the poorest (then the richest) corner of Argentina. The aforementioned last part of The Maker is entitled, simply, Museo (Museum). “Museum” comes to an end a few pages later in a memorable Epilogue, where the author, identified as “JLB,” writes:

A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and people. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the lineaments of his own face.

In other words, JLB likely anticipated Baudrillard’s commentary (the joke is on Baudrillard?) that his fable “possesses the discreet charm of a second-order simulacra,” to the effect that the tatters of empire are us, and that the (imperial) map precedes the (national) territory. How, after all, was one to distinguish between the lines of the map, the territory, the museum, the text, and one’s own face? The possible iterations and simulacra of Tiawanaku’s aging face are, like Atlantis or Babel, youthfully unlimited and periodic. Four or five of these, Peruvian and Argentine, come to my mind at this moment, of which I will only touch the solid surface of lines.

We have an apartment in Palermo Viejo (an old barrio in Buenos Aires) on a shady street named Thames. The parallel street is named Jorge Luis Borges, although locals call it by its old name of Calle Serrano. If you walk down Thames or Borges past the Plaza Italia, the Jardín Botanico, and the Parque Zoológico (all Borgesian haunts), you will come across, at the edge of an upscale district, a small monument to Tiawanaku.

It is a scale model cast or reproduction of the frieze on the fabled Sungate or “Puerta del Sol.” What is the Sungate doing in Buenos Aires? Like the Inca Sun on the Argentine flag, the Sungate is an emblem of Argentine nationhood. It is not only that, upon its solid threshold, Casteli had declared, in an airy speech act, that Indians should share “in the miserable condition of man” as nationals. It is rather that, at least since the great Argentine historian and author of Les races aryennes du Pérou (1871), Vicente Fidel López (1815-1903), the archeological and ethnolinguistic tatters of “Inca” and “American” civilization have provided solid illusions of history for South America’s contemporary nations.

Perhaps the most convincing evidence of this solidity of illusion that is the nation is found in Argentine and Peruvian museums. In the Museo de la Plata, a natural history museum founded in 1884 (the same year as the publication of Richard Inwards’ Temple of the Andes, the source of the Andean Atlantis legends discussed by Gildner), there are several halls dedicated to “American civilizations” which have remained largely unchanged. These dark halls tell the archaeological story of “American man” and “Argentina.” In the main hall stands a striking cast model of the Sungate of Tiawanaku, which serves as a dramaturgical threshold to the mostly Inca collection of artifacts dug up in the northern provinces.

A more impressive iteration of the solid face of Tiawanaku is found on the façade of Lima’s Museo Nacional de la Cultura Peruana. The museum was designed in the “Neo-Incan” style by the Polish architect Malachowski for the private collector, Victor Larco Herrera. It was purchased in 1924 for the nation by President Augusto Leguía, just in time for the close of the extended centennial celebrations of Peruvian independence (1921-24, that is, from San Martin to Bolivar). Initially it was an archaeological museum called, simply, Museo Arqueológico. Notably, the museum’s successor, today called the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Peru (which served Bolivar as his headquarters in Peru) also sports a neo-Tiawanaku façade reminiscent of Inward’s vision in Temple of the Andes.

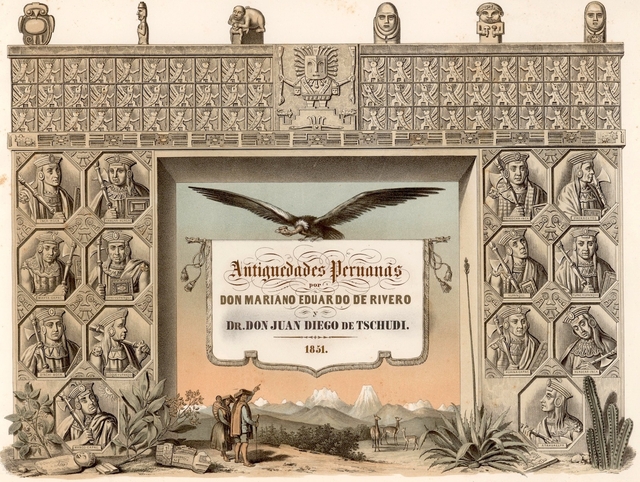

Perhaps inspiration for Malachowski’s museum was drawn from the frontispiece of volume 2 of Mariano de Rivero and Jacob von Tschudi’s Antigüedades Peruanas (Vienna, 1851). This frontispiece was an expression of the National Museum’s collections and mission, articulated by Rivero himself, who was the museum’s founding director.

Tiawanaku-inspired frontispiece, Mariano de Rivero and Jacob von Tschudi, Antigüedades Peruanas (Vienna, 1851), vol. 2. John Carter Brown Library

The Museum that once proudly stood on the edge of an upscale urbanization now languishes on a noisy thoroughfare in a rundown barrio, completely off Lima’s tourist circuit. But there is another, newer iteration of the face or façade of the Sungate that attracts larger crowds. This “Tiahuanaco” is located in the shopping and casino district near the airport. It is, in fact, a casino. Its neon Sungate beckons casual gamblers and hookers of the Lima night to wager on her alluring promise of spectacular treasure.

Following the Mexican philosopher and historian Edmundo O’Gorman, we might upon beholding the face of this nocturnal neon wonder or its cross-town museum cousin, lower our eyes and admit that historical truth is not “an eternal and passive possession” but instead “a demanding lover that, in effect, requires of us a continuous effort of adherence so that she will remain ours; it requires not only an initial acknowledgment or recognition [conocimiento] but repeated acknowledgment or re-recognition [re-conocimiento].”

We may find solid evidence of this demanding lover’s truth in the reconstructions of the original site at Tiawanaku, which have in part followed earlier solid illusions of history imagined by European and North American savants, or in the “coronation” of Bolivian President Juan Evaristo Morales Ayma by shamans (hardly original, since the same kind of rites have been staged for Peruvian Presidents at Machu Picchu).

Some of my favorites, though, are found on the internet, where websites like www.atlantisbolivia.org are only the tip of the virtual iceberg. Given O’Gorman’s reflections, it seems fitting to close these musings with a hyperlink to a foundational scene from “The Real Atlantis.” This image evokes earlier, nineteenth-century illusions of Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, for example, the frontispiece of Volume 1 of Rivero and Tschudi’s Antiguedades Peruanas, which presents the mythical founders of Peruvian or American (if not Atlantan) civilization: