Andean Atlantis: Race, Science and the Nazi Occult in Bolivia

Bolivia, 1928.

As the train steamed around the bend, Lake Titicaca became visible far to the north. The morning sun danced on the water. The majestic Cordillera Real towered beyond. The whistle howled. The engine lurched. After an arduous journey from Berlin, amateur archeologist and future SS commander Edmund Kiss had finally reached his destination: the ruins of the ancient city-state of Tiwanaku.

Tiwanaku had been an object of western fascination since 1549, when a motley band of Spanish conquistadors encountered the ruins deep in the Andes, in what is today Bolivia. Massive stone gateways, enormous granite megaliths, colossal earthworks, intricately-carved stele, mysterious glyphs—the Spaniards marveled at their discovery. Asked of the origins of the ruins and the fate of the civilization that constructed them, local indigenous caciques, or lords, stated that they were from a time long past, and that their original inhabitants had been destroyed by a great flood.

Its antiquity so obvious, its provenance so uncertain, Tiwanaku became one of the great mysteries of modern archeology. During the nineteenth century, the ruins attracted a host of European naturalists that speculated on the civilization that built the monumental structures. Some attributed the site to ancient Egyptians, others to bearded Europeans. All agreed that the ancestors of Lake Titicaca’s local peoples, the Aymara, would have been incapable of accomplishing such a magnificent feat. But if native Andeans hadn’t constructed Tiwanaku, then who had?

Kiss disembarked at Tiwanaku with a bold theory. Tall and bespectacled, his face pink from the unrelenting Altiplano sun, he stood out among the Aymara porters shuffling past. Their rural, ‘uncivilized’ condition only strengthened his conviction that the ruins were built a million years ago by his Aryan ancestors—an ancient Nordic race—who had migrated from the Lost City of Atlantis.

Kiss’s Atlantis theory may have been strange; but stranger still was the fact that it was hardly new. For decades, Bolivians themselves had been pondering their Altantean ancestry—in fact, for many of the same reasons that Kiss had. A connection to Atlantis empowered Bolivia’s European-descendant aristocracy for the very same reasons that it attracted Nazis. It gave them their own private Garden of Eden; and it reinforced the myth of white supremacy.

Athens, 350 BCE.

The legend of Atlantis traces its origins to Plato, who introduced the fabled city in the dialogues Timaeus and Critias. He told of an advanced island civilization beyond the “Pillars of Hercules” that was ruled by a “remarkable dynasty of Kings” endowed with unimaginable wealth. The Kings, having grown overzealous, set out to conquer Athens and enslave its peoples. The Athenians mobilized a heroic defense. But the conflict angered the gods. They sent earthquakes and floods, and Atlantis was “swallowed up by the sea and vanished.”

Classicists have long maintained that Atlantis was a fable that the ancient philosopher invented to warn of the arrogance of power. Over the centuries, however, Plato’s legend acquired an air of truth. During the Renaissance, tales of Atlantis circulated in the European imagination, borne on Humanist inquiry and the discovery of the Americas. Sixteenth-century Spanish chroniclers, from Bartolomé de las Casas to Francisco López de Gómara, drew parallels between the New World and Plato’s Lost City, as did Francis Bacon and Thomas Moore of Great Britain. For French scholars who believed that humans had multiple origins, Atlantis evidenced the existence of man before Adam.

But it was during the late nineteenth century that interest in the fabled Lost City exploded. A Minnesota politician and amateur antiquarian named Ignatius Donnelly is widely credited for the Atlantis revival. In 1882, his bestseller, Atlantis: The Antediluvial World, didn’t just argue that Plato’s Atlantis existed; it claimed that Atlantis had shaped other ancient cultures, from the Maya to the Egyptians. Popular and scientific interest in Atlantis flourished. The Royal Geographic Society of London and the U.S. National Geographic Society were soon sponsoring research on the lost city’s location and funding quixotic and, at times, unnecessarily deadly expeditions.

It’s often overlooked that this “Atlantis revival” coincided with the apogee of polygenesis, one of the fundamental assumptions of scientific racism. Polygenesis was an alternative theory of evolution that rejected the common origins of humans, a belief rooted in Christian creationism and sustained by Darwinian evolution. Polygenists divided humans into separate biological species, or races, that each originated and evolved independently. Races were classified according to innate, inheritable physical attributes—that is, not just skin color, but cranial capacity.

Locating those origins, however, was more complicated. If darker skinned peoples originated in Africa, as polygenists had long assumed, the where did the lighter-skinned peoples come from?

Atlantis would provide nineteenth-century polygenists with their own private Garden of Eden—an idea that appealed especially to Bolivia’s creole, or European-descendant, elite. Since securing their independence from Spain in 1825, they governed—often precariously—the most indigenous country in the hemisphere. Polygenesis provided irrefutable scientific proof of their biological difference and social superiority over native Andean peoples. And deployed alongside the Atlantis myth, it allowed them to claim Tiwanaku as a source of creole heritage.

La Paz, 1925.

Twenty kilometers southeast of Lake Titicaca, on the high plateau straddling Peru and Bolivia, Tiwanaku was once the administrative and ceremonial center of a vast Andean empire. Stratigraphic excavations carried out by Wendell Bennett in the 1930s indicated that the civilization emerged as early as 300 BCE and reached its apex between 600 and 800 AD. Radiocarbon dating subsequently confirmed its age, and archeologists today generally agree that Tiwanaku was built by the ancestors of the Aymara-speaking peoples who populate the Lake Titicaca basin today.

Such a claim was laughable in the Bolivia of Belisario Díaz Romero. Born in La Paz in 1870 to a wealthy family of Spanish provenance, Díaz belonged to an elite class of statesmen and intellectuals that reaped enormous profits by exporting natural resources and exploiting indigenous labor. The republic they governed was overwhelmingly made up of native Americans—largely Aymara- and Quechua-speaking peoples in the highlands and valleys of the Eastern Andean Escarpment.

Creole wealth rested on their access to indigenous labor; their social privilege and political legitimacy rested on a shared conviction that indigenous Bolivians belonged to an inferior race.

Among the creole gentleman scholars who shored up such beliefs, Díaz stood apart. He practiced medicine, wrote history, experimented with botany, and studied geography, linguistics, and archaeology. He was a member of the Geographic Society of La Paz, the National Institute of Statistics, and the National Academy of History. He directed the Meteorological Observatory and the National Museum. Sharp yet soft-spoken, he was the last of Bolivia’s great polymaths.

His most original contribution to Bolivian science was in evolutionary biology. Díaz vehemently rejected creationism, and was an early proponent of natural selection. Yet he dismissed Darwin’s belief in the common origins of the human species, embracing instead the polygenic theories of leading French and German biologists. He divided the human species into “three living and permanent races: the white race, the yellow, and the black.” Homo niger originated in Africa and Homo atlaicus in Asia. Homo atlanticus was a white, ancient Aryan race that came from Atlantis.

Díaz attributed the construction of the monumental architecture at Tiwanaku to Homo atlanticus. Two hundred million years ago, the ancient Aryans migrated west to South America from the original Atlantis across a long-lost land bridge. They settled in the Bolivian Altiplano, which was much different back then. Lake Titicaca was three times larger and the surrounding plain was not windswept and barren. It was lush and tropical, ideal for farming, and abundant in natural resources. Homo atlanticus settled in a shallow valley on the southern shore of the lake, where they constructed a magnificent city.

Díaz not only revealed the origins of the ruins, but explained their supposed contrast with Bolivia’s present-day indigenous population. By measuring skulls, he argued that the cranial measurements of Bolivian Indians were not consistent with those of Homo atlanticus. Rather, the Aymara were descendants of Homo atlaicus, barbaric Asians who arrived in a later migration. It was Homo atlaicus that conquered the ancient city and named it Tiwanaku.

Díaz’s “discoveries” were well received in the elite scientific and political circles of fin-de-siècle La Paz—so well received, in fact, that the government promoted Tiwanaku as the official icon of Bolivia’s Centennial celebrations in 1925.

The months leading up to Independence Day were marked by the typical flourish of statues, monuments, and nationalist speeches. The streets were cleaned and the Parisian townhouses lining the stately calle Montes were repainted. The President even issued a supreme decree prohibiting Indians from sidewalks and plazas. And when the big day finally came, creole aristocrats could raise their glass in the name of the Republic and toast their ancient ancestors from Tiwanaku, the “primitive metropolis of South American whites.”

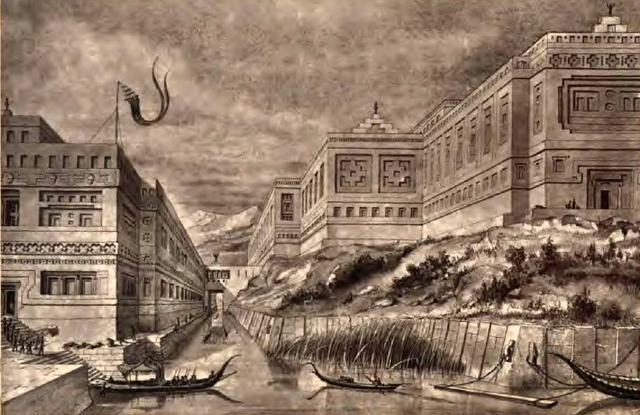

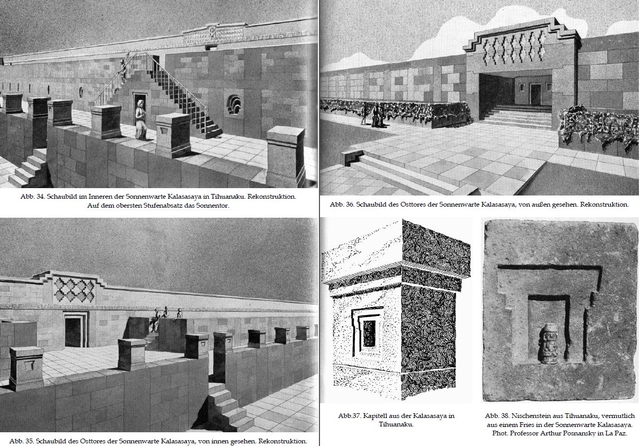

Edmund Kiss’s hypothetical reconstructions of Tiwanaku in his book Das gläserne Meer (Leipzig, 1930).

Berlin, 1939.

Whether or not the German writer Edmund Kiss met Díaz Romero during his stay in Bolivia remains uncertain. But Kiss was undoubtedly exposed to his ideas by Arthur Posnansky, a swashbuckling Austrian capitalist, amateur archaeologist, and international gentleman of science. Tiwanaku was Posnansky’s enduring obsession. From 1903, the year he settled in Bolivia, to his death in 1946, he published over 130 titles on the site, in four languages.

What brought Kiss and Posnansky together—and what drew Kiss to Tiwanaku in the first place—was Kiss’s commitment to German ethnic nationalism and his obsession with the mythic past. Neither were uncommon in the Weimar Republic. As the Nazi Party expanded during the 1920s and 1930s, right-wing romantic nationalists celebrated an idealized folk culture as the essence of German nationhood.

What brought Kiss and Posnansky together—and what drew Kiss to Tiwanaku in the first place—was Kiss’s commitment to German ethnic nationalism and his obsession with the mythic past. Neither were uncommon in the Weimar Republic. As the Nazi Party expanded during the 1920s and 1930s, right-wing romantic nationalists celebrated an idealized folk culture as the essence of German nationhood.

Where archaeological evidence of Aryan Atlanteans was lacking, an elaborate theory called Glacier Cosmology did the trick. A moon had once collided with Earth, destroying Atlantis and covering the planet with glaciers. What led Kiss to Tiwanaku was his belief that following the cataclysm, survivors of that ancient Nordic civilization took refuge in the high Andes, one of the few places where life was still possible. Kiss found Posnansky while researching the question and in 1928 he set off to Bolivia to study the ruins.

Kiss spent almost a year at Tiwanaku. Always wearing the same long white smock and Panama hat, he carefully surveyed the ruins and their relative position to the sun, stars, and moon. Kneeling, notepad on thigh, he studied the glyphs for meaning, sometimes for hours, seeking clues to the identity of the ancient architects. Day after day in the basement of the National Museum he studied skulls, wondering if the ancient Tiwanakan’s elongated crania were artificially deformed, or belonged to a superior Nordic race.

Back in Germany, his work was a wild success. “The works of art and the architectural style of the prehistoric city are certainly not of Indian origin,” Kiss had concluded. “Rather they are probably the creations of Nordic men who arrived in the Andean highlands as representatives of a special civilization.” Kiss further publicized his finding with a popular tertiary of science fiction novels that chronicled the rise, decline, and ultimate triumph of the ancient Aryans.

Nazi officials seized on Kiss’s work and featured the ancient Nordic city of Tiwanaku in party newspapers and Hitler Youth publications. Kiss was soon put in touch with Heinrich Himmler, leader of the Nazi SS and a principle architect of the Holocaust. In 1935, Himmler had founded a new SS think tank called the Ahnenerbe to conduct social scientific research into the history of the Aryan peoples. So far, he had sent archeological missions to Scandinavia, France, Tibet, and Antarctica in search of the ancient origins of the Aryan race.

Now he wanted Kiss to lead a trip to Bolivia, to Tiwanaku, the ancient Nordic civilization in the Andes. Working for much of 1938 and 1939, Kiss assembled a crack team of Nazi scientists for the job. Their objective: reveal the presence of the Master Race in prehistoric South America, and dispel, once and for all, the mystery surrounding the Tiwanaku ruins.

The expedition never happened. When Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, the war took precedence. Kiss, already an officer in the SS, was dispatched to Warsaw, and then took command of Wolfschanze, one of Hilter’s military headquarters in East Prussia. In 1945, he surrendered to the Allies and was imprisoned alongside other Nazi war criminals. At the “de-nazification” hearings, Kiss was initially classified a “major offender,” but he pleaded for and won the lesser status of “fellow traveler”—on account of his archaeological research. He remained committed to his Atlantis-Tiwanaku thesis until his death in 1960.

Here, Now.

Like Kiss, Díaz and Posnansky also died long ago—and their fantastic interpretations of Tiwanaku have since been thoroughly discredited. Nonetheless, their legacy lives on. Popular television series like Ancient Aliens and Secrets of the Dead continue to explore the Tiwanaku-Atlantis connection. Bestselling books by Erich von Däniken and Graham Hancock go further, attributing the construction of Tiwanaku to ancient extraterrestrial beings.

Though it may be hard to stomach, the survival of the Atlantis myth is certainly not surprising. Plato’s Lost City has proven both timeless and universal in the western imagination. Its timelessness lies in its capacity to reveal the mysteries of human origins; its universal appeal, in its unlimited imaginary potential. And lest we forget: the legend of Atlantis evolved alongside dangerous theories of race that reinforced white supremacy for Aryan nationalists and Bolivian creoles alike. Attributing the construction of Tiwanaku to ancient extraterrestrial beings only perpetuates this nefarious myth. When we wonder if Tiwanaku was built by Atlanteans or by Aliens, those assumptions are based on the same twisted logic that drove men like Díaz, Posnansky, and Kiss: that Andean peoples could not have built Tiwanaku.

And that’s the greatest myth of all.