Who wouldn’t want to live in someone else’s utopia?

Who wouldn’t want to live in someone else’s utopia?

How the Space Age Imagined 2014: Asimov’s Predictions, Revisited

Earlier this year, you may have come across a dispatch from the New York World’s Fair that Isaac Asimov wrote in 1964 but which went viral fifty years later, appearing on NPR, Slate, and countless Facebook pages in the days following New Year’s Eve. With the launch of our seventh issue, “Futures of the Past,” it seemed like a good time to revisit Asimov’s remarkable essay, which you can read in full here. After all, our issue’s cover hails from the very displays that Asimov gazed at with rapt attention in the summer of ’64. It shows a General Motors diorama of an advanced colony of climate scientists who monitor the planet’s weather from their station in Antarctica. To modern eyes, it looks a bit like Devo conducting a space launch:

But for Asimov and the hundreds of thousands of visitors who thronged to these displays, they weren’t retro curiosities: they were harbingers of a future that seemed very real. It’s one that we’re still waiting for.

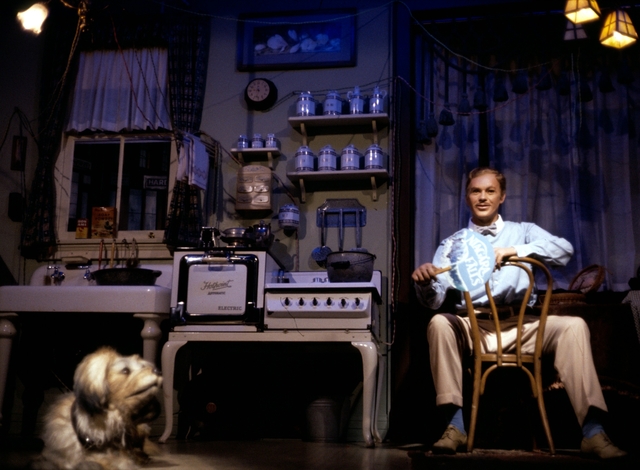

Isaac Asimov was especially thrilled by the General Electric pavilion, with its “cheerful, lifelike dummies” inhabiting model homes filled with twenty-first century conveniences. Asimov professed admiration for the historical dioramas that opened the display—“the scenes set in 1900, 1920, 1940 and 1960 [which] show the advances of electrical appliances and the changes they are bringing to living.” Altered versions of these dioramas still exist at Disney World, and they offer an interesting glimpse into how the World’s Fair cast its glance backwards as well as forwards. (They’re also super creepy in an uncanny valley sort of way).

A revised version of the 1920 scene from the General Electric “Carousel of Progress,” which was readapted for display at Disney World in 1972. Wikimedia Commons

Why not carry the “Carousel of Progress” into the future, Asimov wondered? “What will the World’s Fair of 2014 be like?” he asked in his August 16 New York Times op-ed, and proceeded to answer his own question with a series of surprisingly thoughtful predictions:

One thought that occurs to me is that men will continue to withdraw from nature in order to create an environment that will suit them better. By 2014, electroluminescent panels will be in common use. Ceilings and walls will glow softly, and in a variety of colors that will change at the touch of a push button.

Asimov’s fixation on home technology has a distinctly contemporary ring to it, given recent announcements by Apple and Google signaling their entry into the so-called “smart home” market. (Matt Novak of the excellent blog Paleofuture walked his readers through Asimov’s “shockingly conservative” predictions on this score.)

Windows need be no more than an archaic touch, and even when present will be polarized to block out the harsh sunlight. The degree of opacity of the glass may even be made to alter automatically in accordance with the intensity of the light falling upon it. There is an underground house at the fair which is a sign of the future. If its windows are not polarized, they can nevertheless alter the “scenery” by changes in lighting.

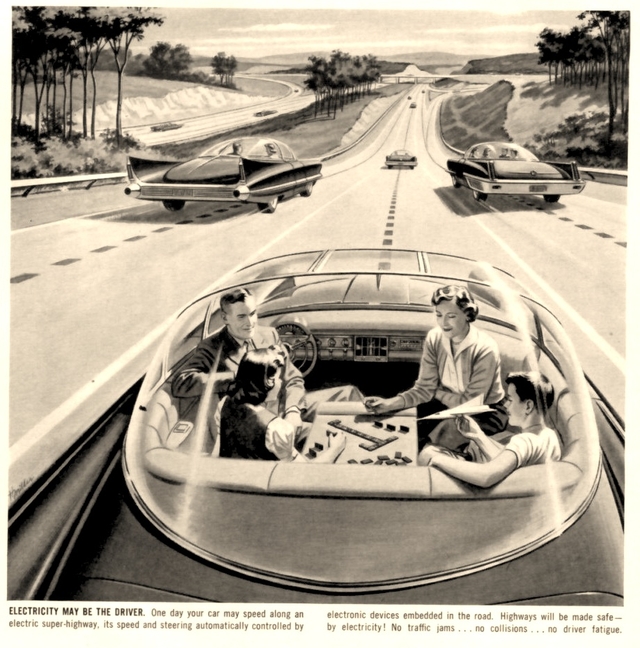

Asimov believed that “robots will neither be common nor very good in 2014,” but that gadgets will have proliferated: food replicators that can be pre-programmed to serve up coffee and toast on demand, wireless appliances powered by nuclear batteries, self-driving cars with what Asimov calls “robot brains,” moving sidewalks, and the like.

“As for television, wall screens will have replaced the ordinary set,” Asimov wrote, anticipating both LED flat screens and emerging glasses-free 3-D technology, “but transparent cubes will be making their appearance in which three-dimensional viewing will be possible.” And his predictions about space turn out to be accurately pessimistic (aside from the assumption of a lunar colony): “by 2014, only unmanned ships will have landed on Mars, though a manned expedition will be in the works.”

The futuristic architectural stylings of the Kodak Pavilion, with the GE pavilion visible in the distance. Randy Treadway, Worldsfaircommunity.org

Asimov even anticipates the rise of vegan favorites like Tofurkey: “the 2014 fair will feature an Algae Bar at which ‘mock turkey’ and ‘pseudosteak’ will be served. It won’t be bad at all (if you can dig up those premium prices).”

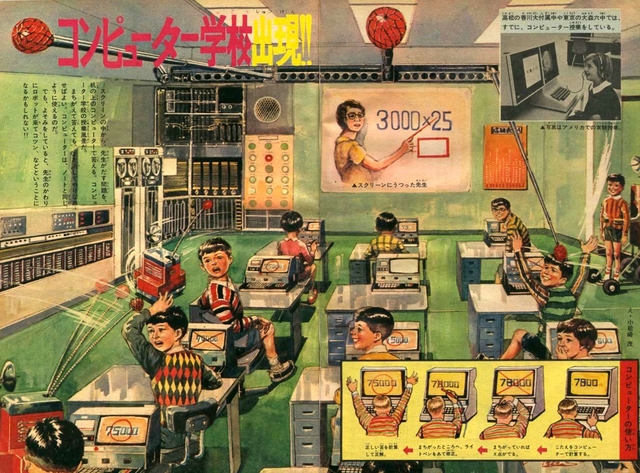

The only point at which Asimov’s predictive skills really fail him, crucially, is in predicting the future of labor. By 2014, he believes, the human race will “have become largely a race of machine tenders,” living lives of “enforced leisure” as machines take care of virtually all mechanical tasks. Granted, there’s something to this—Asimov’s prediction of a future classroom oriented around machine learning rather than live human instruction is the flipped classroom, avant la lettre.

The “watchful robots” of a future classroom envisioned by Japan’s Shonen Sunday newspaper in 1969 may not have been quite what Asimov (or contemporary proponents of e-learning) had in mind. Dark Roasted Blend

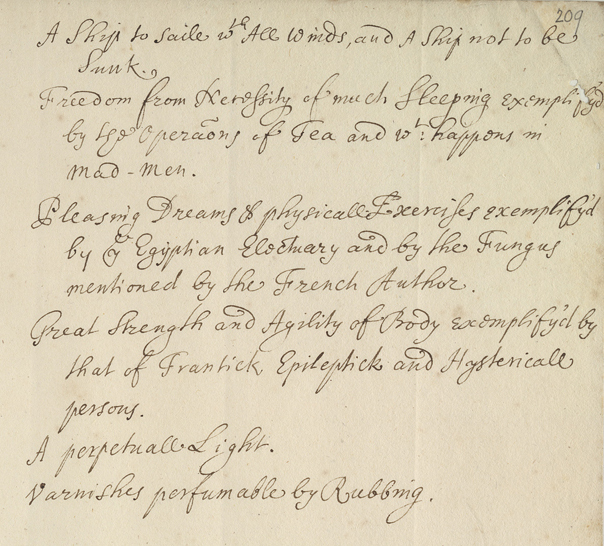

Yet as we point out in our editorial letter, thinking about the future can often lead us into restrictive binaries: we’ll live in either a utopia or a dystopia, a work-free wonderland of gadgets or a post-apocalyptic, nuked-out hellscape. The articles in “Futures of the Past” engage with both of these imagined futures, from Rebecca Onion writing about how 1980s kids grappled with fears of nuclear annihilation to Anna Marie Roos on the optimistic predictions of the 17th century scientist Robert Boyle, who hoped for everything from new drugs and scratch ’n sniff technology (“Varnishes perfumable by Rubbing”) to “A perpetuall Light.”

As Brian Merchant, writing for Motherboard, has pointed out, it’s fun to pick and choose the bits of predictions that end up being unexpectedly right (Asimov’s inspired guess that world population would be 6.5 billion in 2014, or his anticipation of smartphones) or wildly wrong (the life of robot-enforced leisure stuff). I agree with Merchant that

picking apart Asimov’s predictions and tallying up the wrongs and the rights is missing the point. To treat Asimov’s essay as a spate of Nostradamus-style prophecies is to misunderstand its aim; as with most good sci-fi, the important part is how it reflects on the present in which it was written.

But it’s also worth pausing to think about how these predictions reflect the present in which they’re read. Dreams of the future are always reshaped to fit what their readers demand of them. Asimov went viral not just because he seemed to predict Google Cars and LED lights, but because his utopian dreams of these gadgets validated our own yearning for them.

After all, who wouldn’t want to live in someone else’s utopia?

Yet as we point out in our editorial letter, “predictions are always political acts.” We pick and choose from retro curiosities and nostalgic futures to find the bits that make us feel okay about the trajectory of the past and the future that we’re hurtling into. But sometimes confronting those pasts and imagined futures can bring some uncomfortable realities to the fore.

Just the other day, my mother forwarded me a chain email called “Old Memories…” that her octagenarian friend had sent her. It started out with the typical scenes of Space Age nostalgia, seas of smiling faces wearing 3D glasses, an X-Ray beauty pageant from 1956, and the like. And then I hit this picture:

It was a harsh reminder of the dangers of historical nostalgia, and of seeing both the past and future alike through rosy spectacles. Did the dioramas and futuristic sets that Asimov saw that day in August include similar scenes of segregation? I’ve looked through dozens of photos from the Futurama II exhibits and have yet to see anything but a sea of white faces. As Yale PhD candidate Erin Pineda reminds us in her upcoming Appendix article about how the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality attempted to block the opening of the 1964 World’s Fair, sometimes dreams of a utopian future can obscure harsh present-day realities.

At its core, the World’s Fair was entertainment, and entertaining it was. But there is always a cost that comes along with creating and selling a pristine version of past, present, and future; there is a cost that comes with being seduced by it, believing we can simply buy a better future or trust in technological innovation to invent one for us, in spite of the evidence of the troubled present and the wreckage of the past.

Today we can look back at Asimov’s predictions with the 20/20 vision of hindsight. But with predictions of miraculous technological advances growing more confident with every passing year, is it possible that we’re falling into the same trap?