Perchance to Dream: Science and the Future

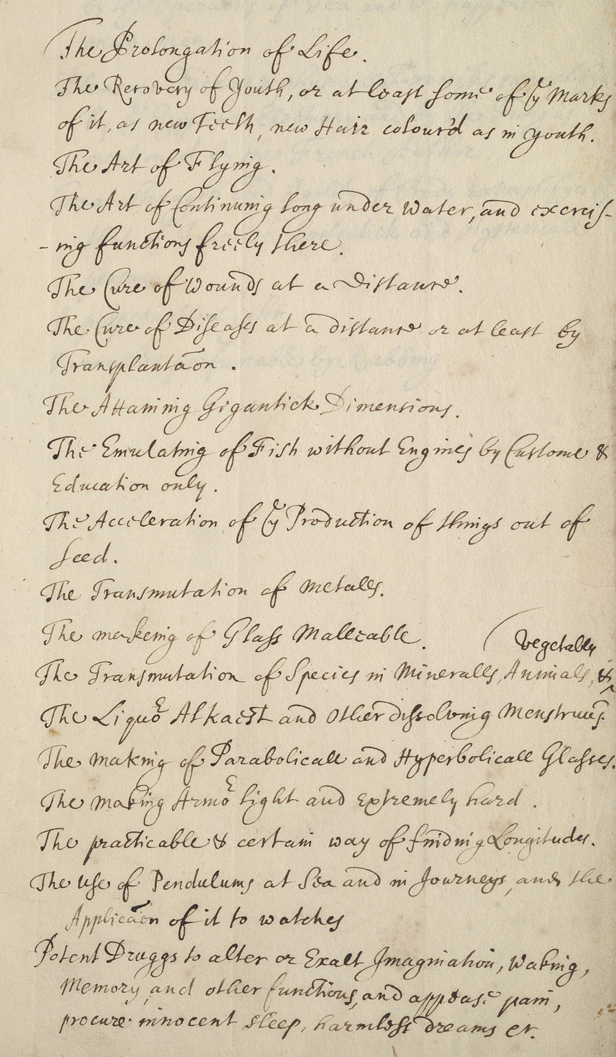

Robert Boyle’s remarkable to-do list for future scientists ranged from “the Art of Flying” to “Potent Druggs to alter or Exalt Imagination.”

Robert Boyle, the seventeenth-century polymath, chemist, and fellow of the Royal Society, left in his papers a twenty-four-item list of predictions of the future. Though he discovered the famous law of gaseous pressure and volume that bears his name, Boyle was not just blowing hot air. The Royal Society was the first government-sponsored scientific society in the world. As part of a charter granted by King Charles II, the Society charged itself, in that delightfully immodest manner characteristic of the Restoration, to “extend not only the boundaries of the Empire, but also the very arts and sciences.”

So, the list Boyle left us was all about boundary breaking, and a successful list it was. Many of the items, such as “the art of flying,” “the art of continuing long under water, and exercising functions freely there,” and even “Varnishes perfumable by Rubbing” have been achieved in the form of airplanes, scuba diving, and scratch-and-sniff. A designer even recently created minty scratch-and-sniff jeans, the smell lasting through ten washes.

Boyle’s list reminds us that science has always been bound together with novelty and entertainment. The early Royal Society’s meetings were in fact characterized as “entertainments” for wealthy and interested gentlemen, and Boyle himself demonstrated a trick of writing with a finger dipped into luminescent phosphorus, the “icy noctiluca” as he termed it, making enchanting displays.

Boyle’s “Desiderata,” transcribed:

The Prolongation of Life.

The Recovery of Youth, or at least some of the Marks of it, as new Teeth, new Hair colour’d as in youth.

The Art of Flying.

The Art of Continuing long under water, and exercising functions freely there.

The Cure of Wounds at a Distance.

The Cure of Diseases at a distance or at least by Transplantation.

The Attaining Gigantick Dimensions.

The Emulating of Fish without Engines by Custome and Education only.

The Acceleration of the Production of things out of Seed.

The Transmutation of Metalls.

The makeing of Glass Malleable.

The Transmutation of Species in Mineralls, Animals, and Vegetables.

The Liquid Alkaest and Other dissolving Menstruums.

The making of Parabolicall and Hyperbolicall Glasses.

The making Armor light and extremely hard.

The practicable and certain way of finding Longitudes.

The use of Pendulums at Sea and in Journeys, and the Application of it to watches.

Potent Druggs to alter or Exalt Imagination, Waking, Memory, and other functions, and appease pain, procure innocent sleep, harmless dreams, etc.

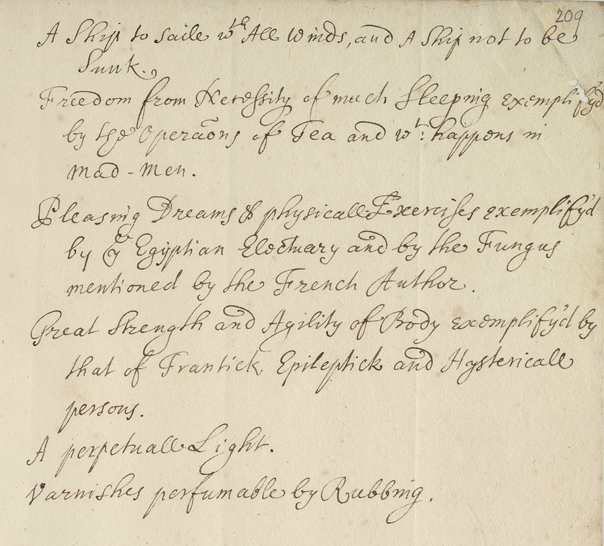

A Ship to saile with All Winds, and A Ship not to be Sunk.

Freedom from Necessity of much Sleeping exemplify’d by the Operations of Tea and what happens in Mad-Men.

Pleasing Dreams and physicall Exercises exemplify’d by the Egyptian Electuary and by the Fungus mentioned by the French Author.

Great Strength and Agility of Body exemplify’d by that of Frantick Epileptick and Hystericall persons.

A perpetuall Light.Varnishes perfumable by Rubbing.

These wish lists of future predictions derived in part from the natural philosophical projects of Francis Bacon (1561-1626), whose scientific method of empirical observation and induction were revered by the Royal Society. As the historian Vera Keller has demonstrated, invention—whether ancient, modern, or not-yet-discovered—was a major preoccupation of early modern thinkers. Bacon, in particular, formulated the idea of the desiderata or wish list, or inventions that were seen as particularly desirable. Keller writes that these lists served as “markers for what humankind might achieve together… serving to expand the horizon of possibility.” Some of his motivation for making such lists was purely political, economic and practical, as Bacon called them, “experiments of fruit,” whereas other investigations were to advance knowledge, or for “experiments of light.” Wish lists appeared as part of political projects before they appeared as scientific projects; desiderata about improvements in navigation, for example, were written with the aim of extending England’s empire.

By surpassing the bounds of empire, nature, and knowledge via experimentation, Bacon argued that humankind could restore itself to its perfect pre-lapsarian state before the fall in the Garden of Eden. Humans could use knowledge of the natural world to have dominion over nature, not just for material benefit but also for charitable purposes, to improve “man’s estate.” Because of this important aim, Bacon also argued that it was a crucial job of the historian to keep old technologies from being lost to the mists of time, as well as to open up new lines of future enquiry.

As an historian of science, I thought I’d follow Bacon’s advice about listing and writing about past and future inventions. I decided to see what the contemporary Royal Society thought about its visions for the future. My first point of call was the Society’s blog of advice to science policy makers. Much of the advice is dedicated to inventing technologies not only to control nature as Bacon advised, but also to mitigate the effects of human intervention on the planet. Reducing sources or enhancing the sinks of greenhouse gases, promoting sustainable development, and using science to reduce the impact of natural disasters are common themes, but so is geo-engineering, or as the blog describes, a “suite of techniques to reduce global warming by intervening in the Earth’s climate system. It can involve removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, or reflecting a small proportion of sunlight back into space.” Bacon himself in The New Atlantis envisioned a mysterious island nation whose citizens had “great and spacious houses, where we imitate and demonstrate meteors—as snow, hail, rain, some artificial rains of bodies and not of water, thunders, lightnings.” Scientists have always dreamed of controlling the weather.

The Society’s blog is entitled In Verba, a rather geeky pun on its motto Nullius in verba (Take nobody’s word for it, find out for yourself). I therefore decided to ask a few Fellows of the Royal Society this question: If you were making a 21st century wish list of scientific discoveries or future innovations, what would you include?

Here are my results.

I’d like someone to solve one of the greatest mysteries of sexual selection—why the females of most species are promiscuous.

I would also like to wish for fewer restrictions on research funding; less bureaucracy; more blue skies research; more honesty in publishing; and the greater representation of women in science.

—Professor Tim R. Birkhead, FRS, University of Sheffield. Ornithologist and best-selling author who specializes in the mechanism of sexual selection in birds.

Diagnostic kit with behavioral/neurological measures for neuro-developmental disorders such as autism, dyslexia and dyspraxia.

Knowing the reasons why their child is not developing in the normal way would prevent a lot of misery and unnecessary self-blame for affected families. Educational interventions could be put in place early before the failure to meet unrealistic expectations becomes a deeply frustrating everyday experience.

Personalized education based on individual preferences and abilities.

The processes underlying learning, attention and motivation need to be fully understood so that they can be used to design educational programmes for everybody, and at any age to adapt to a continuously changing cultural environment.

—Professor Uta Frith, DBE FBA FRS FMedSci, University College London. Psychologist. Professor Uta Frith is best known for her research on autism spectrum disorders, and is one of the initiators of the study of Asperger’s Syndrome in the UK. Her work on reading development, spelling and dyslexia has been highly influential.

To understand how and why the brain generates sleep.

We spend approximately 36% of our lives asleep. This makes sleep the single most important behaviour we experience yet as individuals and as a society we disregard it. We already know that sleep is not the simple suspension of activity but a state that is associated with critical brain functions such as memory consolidation and information processing, whilst in the rest of the body tissue repair, toxin clearance and the rebuilding of energy reserves all occur during sleep. We also know that disrupted sleep is associated with multiple health problems including cognitive impairment, impulsive behaviur, mental illness, metabolic abnormalities including diabetes II, immune suppression, increased risk of cancer, cardiovascular problems and ultimately death. Our waking experience and health depends upon “good sleep”, but what is good sleep; how does the brain generate sleep; why is our health so dependent upon sleep; and could we develop drugs to fully mimic sleep?

This wish is fairly similar to Boyle’s: “Potent Druggs to alter or Exalt Imagination, Waking, Memory, and other functions, and appease pain, procure innocent sleep, harmless dreams, etc”

—Professor Russell G. Foster FRS FMedSci, Head, Nuffield Laboratory of Ophthalmology. Director, Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute Fellow, Brasenose College, University of Oxford. His research interests span both visual and circadian neurobiology with the main focus on the mechanisms whereby light regulates vertebrate circadian rhythms.

Designing molecules to produce particular effects.

—Professor Martyn Poliakoff, CBE FRS, is the Foreign Secretary and Vice-president of the Royal Society. He is also a green chemist, working on gaining insights into fundamental chemistry and on developing environmentally acceptable chemical processes and materials.

The evolution of multi-cellular life on land was a major event in Earth history. I would like us to be able to link genetics to geochemistry to understand how plants left the water and established complex terrestrial ecosystems on the dry continental surfaces approximately 500 million years ago.

I would also like us to discover if there is extraterrestrial life and find out how similar or different it is to life on Earth. This knowledge could be of great benefit to avoid human extinction.

—Professor Liam Dolan, FRS, is the Sherardian Professor of Botany, University of Oxford. His research is aimed at understanding general principles of cell development and evolution using specialized rooting cells such as rhizoids and root hairs as models. In particular, he is interested in the role of root hairs in enhancing nutrient uptake in crops.

To discover some early fossil land plants and to find the technology that would allow identification of their affinities.

—Professor Dianne Edwards, CBE ScD FRSE FLSW FRS, is a Distinguished Research Professor at Cardiff University. A paleobotanist, Professor Edwards is distinguished for her investigations into the nature of the earliest land plant fossils. By skillful application of scanning electron microscopy, and the painstaking use of such techniques as the preparation of polished surfaces of pyritised plant tissue, she has elucidated the anatomy and morphology of numerous late Silurian and early Devonian plants and thrown new light on the evolutionary events surrounding the first colonization of the land. Professor Edwards is President of the Linnean Society of London.

I would like to thank the Fellows of the Royal Society, Jo McManus, and Mr. Keith Moore, Head of Library and Information Services at the Royal Society, for their assistance with this article.