Honey, You’re Scaring the Kids

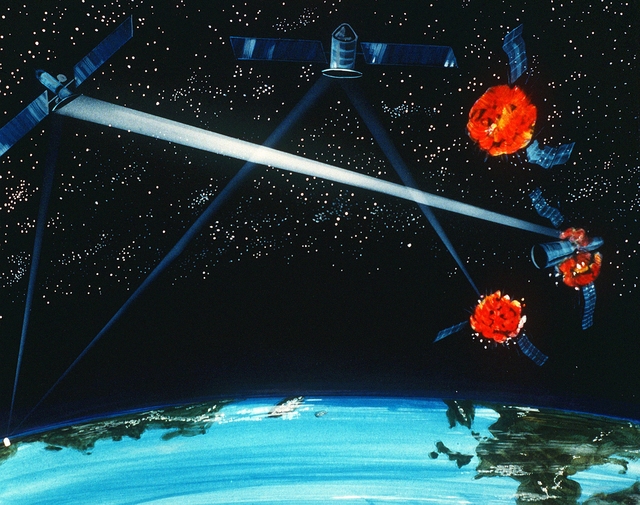

How 1980s childhoods changed the way America thought about the Bomb. A US government artist’s depiction of an anti-nuclear missile laser weapon, 1984. (Wikimedia Commons)

In the fall of 1983, a TV movie ruined Alexander Zaitchik’s ninth birthday party. He wasn’t supposed to see The Day After, a two-hour film set in Lawrence, Kansas that follows a cast of everyday American characters into and through a nuclear strike, but he lingered at the top of the stairs as his family watched, catching snatches of the images and sounds.

Recalling the event years later, Zaitchik remembered his eight-year-old self anxiously playing through the circumstances of a nuclear attack:

If it happens in the afternoon, do we run toward home, or away from the city and the blast? If it happens at night, do we let our parents huddle over us in the basement, or do we stand on the rooftop, chests forward, praying the first shock wave dematerializes our family without pain?

Preoccupied, Zaitchik wrote, he barely noticed his birthday celebration. “It was the first birthday party I felt no excitement over. The ice cream cake was tasteless. The Return of the Jedi action figures I unwrapped were pieces of plastic, destined to burn up with everything else.”

Zaitchik’s memories of November, 1983 have the special hyperbolic flavor of juxtaposition: the sweet cultural hallmarks of an 80s childhood, ice cream cake and Return of the Jedi, mashed up with the darkness of nightmares. He’s not the only 80s child with strong memories of this movie. Anecdotal evidence of its impact abounds. Writer Steven Church’s 2010 memoir The Day After The Day After: My Atomic Angst uses the broadcast as an anchoring point to explore all of the anxieties of childhood. The director of the film, Nicholas Meyer, still receives correspondence from kid viewers, now grown up, who were deeply affected.

The broadcast and its attendant hype has become a touchstone in any academic history of American film and television in the nuclear age. An estimated 100 million people watched The Day After. The broadcast came along with intense media coverage, government commentary, and psychological advice.

Discussions of the movie’s impact revealed sharp lines between conservative voices who preferred to steer clear of what they termed emotional reactions (or, as William F. Buckley, Jr. would put it, “junk thought”) in policy discussions, and activists who found a bloodless conversation about the issues to be dangerous and inhuman. In this conversation around the emotions that the movie might provoke, the motif of younger children’s fears, and older children’s cynicism, emerged again and again.

This was something new to the 1980s. While political discourse early in the Cold War invoked childhood, it did so to strengthen nationalist consensus, as anthropologist Sharon Stephens has argued. A finger pointed to the family’s needs justified containment culture. Child psychologists of the early Cold War did worry about kids’ thoughts about the bomb, with groups like the Committee for the Study of War Tensions in Children analyzing possible effects of constant public nuclear talk on kids’ psyches. But the concern didn’t translate to political action.

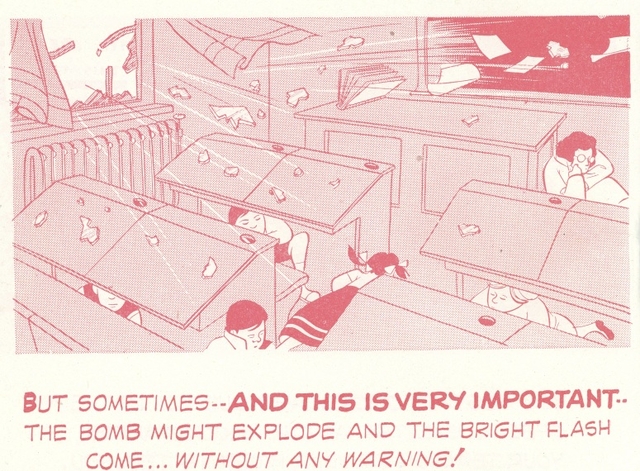

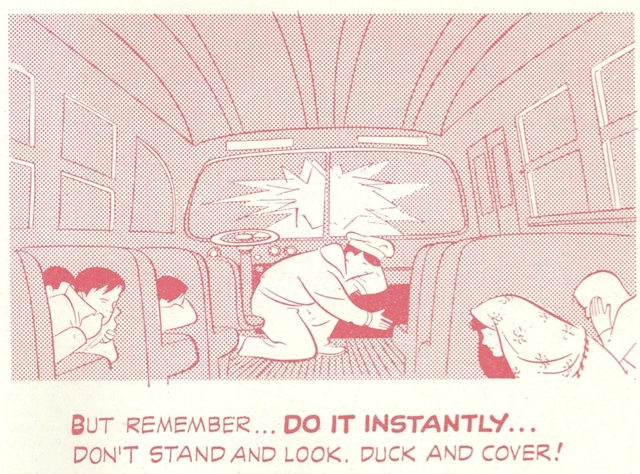

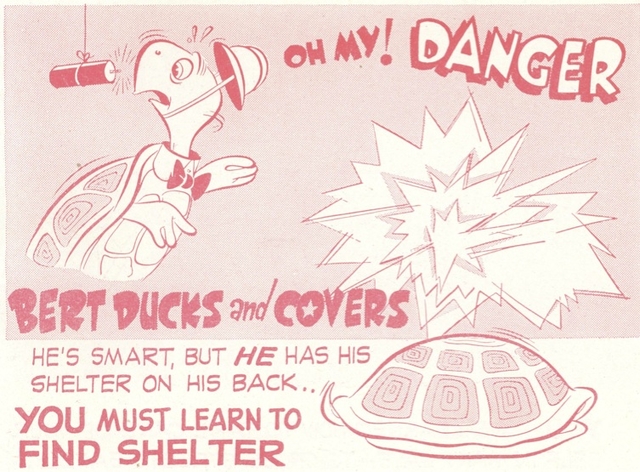

Kid fears of the 1950s were met with what now looks like condescending, palliative civil-defense culture. Cartoons that are now the object of our historical scorn (Duck and Cover primary among them) explained the possible consequences of nuclear war, recommended putting your head under a picnic blanket if the bomb were to come while you were in the park, and compared radiation burns to sunburn.

From 1951 comic-book version of “Bert the Turtle,” published by the US Federal Civil Defense Administration and Archer Productions. Government Comics Collection

I’m not going to argue that no children were afraid of nuclear war before the early 1980s. Indeed, historian Spencer Weart, in his book about nuclear fear, remembers sitting in front of the television in April, 1954, watching the filmed Operation Ivy test of a hydrogen bomb in “dread fascination.” Rather, it was the public acknowledgement and politicization of children’s fears that was something remarkable and new.

In the thirty-year gap between Duck and Cover and The Day After, children’s nuclear fears came to be seen as admonishments. In a pre-Day After column, the Washington Post’s Ellen Goodman argued that the difference between her generation’s experience and the present day’s was in leadership. “Most of us have grown up under the threat of extinction,” she wrote. “In the past we behaved much like children who entrust their anxieties to powerful adults in the belief that responsible grown-ups will take care of them. We entrusted nuclear anxiety to our leaders.” Adults and children alike had become afraid, she wrote, because those in charge were clearly “not careful enough.”

Writing about fear and childhood between 1850 and 1950, historians Peter Stearns and Timothy Haggerty point to a transition in expectations when it comes to parental duties to prevent and allay kids’ fears. Victorian parents, they argue, were counseled to see fear as a productive obstacle, and to help children move past anxiety into adulthood. Kid fears didn’t receive much credence.

Around the turn of the century, advice to parents began to recognize specific fears as endemic to childhood: animals, the dark. “Fear and its management became far more problematic than they had been in nineteenth-century culture,” Stearns and Haggerty write. “Avoiding fear began to make much more sense to many prescribers than accepting its challenge as part of building moral character.”

The nuclear kid fears of the early 1980s were not just personal and domestic. They were public fears, writ small. In the discourse over nuclear fear, dismay over the distress of children became wrapped up with the guilt that a parent must feel at a child’s affliction, and amplified by the parent’s own apprehensions. Unlike the boogeyman, nuclear annihilation was real, and adults made it.

Contemporary analysts studied fears as a barometer of underlying social trauma. Ethicist Roger L. Shinn, writing about public awareness of nuclear threat in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, saw children as the true indicator of whether or not the public was even thinking about nuclear war: “There are some signs that the public seems largely unaware of the issue,” he wrote in 1984. “But other signs, sometimes in the inadvertent remarks of children, reveal a deep awareness that we live in a fragile civilization that could go up in a mushroom cloud.”

When The Day After was broadcast, things looked dark. In its first term, the Reagan administration took little action on arms control, and sometimes appeared openly hostile to the issue, preferring to invest in an enhanced arsenal and to plan for blue-sky defense systems. As historian Lawrence Badash points out, in the early 80s anti-nuclear activists shifted focus from nuclear power to disarmament: “Half of the American organizations that focused on peace, disarmament, defense, nuclear war, and weapons were founded during Reagan’s first term.” The 1982 publication of Jonathan Schell’s book The Fate of the Earth galvanized the anti-nuclear movement still further with its dire warnings of the consequences of nuclear bombs. In the fall of 1983, Carl Sagan had just published an article in Parade Magazine on the possible long-term effects of nuclear winter. And the USSR and NATO had escalated their nuclear presences in Europe, with NATO placing Pershing and cruise missiles on European soil.

Anti-nuclear demonstrators in Berkshire, UK, at the Greenham Common airbase, protest the arrival of 96 American cruise missiles in 1983. The Greenham demonstrators were mostly women, who leveraged gender and their status as mothers in their arguments. Daily Telegraph

In this context, The Day After seemed poised to catalyze simmering anxieties. Critic Tom Shales, writing in the Washington Post with his tongue slightly in cheek, explicitly compared the film itself to a bomb: “One can imagine an ABC engineer quivering slightly as he presses the button on Sunday night that will send the film into millions and millions of American homes.”

The National Education Association issued a parental advisory for the film—its first. A starkly worded memo circulated in the New York City school system summed up the dilemma posed by the film, which was seen as both learning opportunity and dangerous agent:

ABC’s intention in presenting it is to educate the public about nuclear war. However, the scenes of terrible destruction, people being vaporized, mass graves, and death from radiation sickness may not be helpful or educational for children and young people. This is not ‘just one more horror film.’ Adults can confidently tell youngsters that ghosts and vampires don’t exist. But the threat of nuclear war is real.

By 1983, researchers had been looking at the effects of television on young people for two decades, asking how time in front of the television affected learning, social relationships, and responses to advertising. Since the early 1960s, concerns over television violence and its possible impact on children’s behavior had particularly preoccupied researchers and the public.

Comments offered to media outlets before The Day After reflected this history of concern. Dorothy Singer, co-director of the Family Television Research and Consultation Center at Yale, gave the New York Times a very graphic depiction of the potential dangers for young children who saw the film without warning: “I think ABC can do a lot more to alert parents and kids to the fact that this is not just another made-for-television movie … I’m worried about the baby sitter who’s heard about the show and turns it on, and then the 4-year-old crawls into her lap to watch it with her.” Singer’s scenario pictures the truthfulness of the film as a deeply damaging shockwave, exploding into young people’s consciousness without warning and wreaking havoc.

Many psychiatrists interviewed by the media before the movie aired took their cues from Robert Jay Lifton’s theory of “psychic numbing,” arrived at in his work on the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing. In 1982, Lifton argued that nuclear fears had the potential to create a dangerous apathy. Experts warning about The Day After’s effects on older children were intent upon warding away “cynicism” or “numbness.” Dr. Kenneth Porter, family therapist and assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and co-chair of the NY chapter of Physicians for Social Responsibility, told the Times: “It’s extremely important for people to talk about ‘The Day After’ themselves and not let television do the talking and feeling for them. If they do that, they’ll lock feelings of despair and fatalism inside them.”

In keeping with this therapeutic intent, ABC drew up a viewers’ guide and distributed half a million copies of the viewers’ guide to schools and community groups, inviting prospective viewers to write in for a free copy. The guide (you can see a full PDF here, thanks to the blog CONELRAD) assumes fear as a default stance. It features an epigraph by Camus: “The seventeenth century was the century of mathematics, the eighteenth that of the physical sciences and the nineteenth that of biology. Our twentieth century is the century of fear.” Before viewing, audiences, young and old, should talk to one other about their anticipated reactions:

“Complete this sentence: Whenever I try to talk about my feelings on nuclear war, what usually happens is __.”

“Some people say that Americans worry about too many things which may never come to pass. Do you agree or disagree? Discuss.”

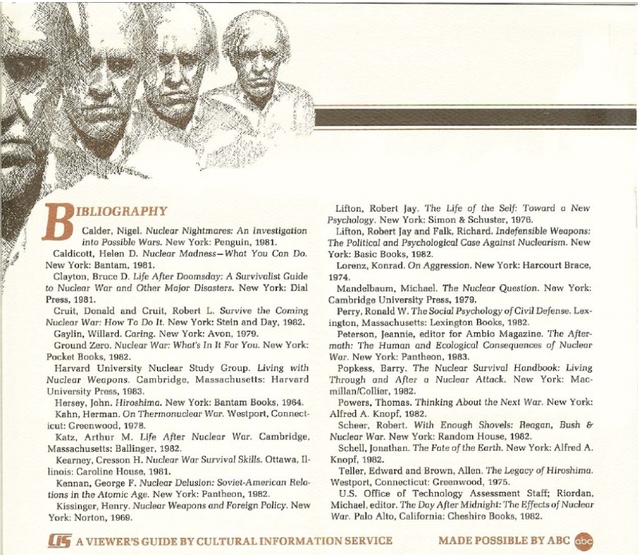

The bibliography included with the ABC viewers’ guide suggested a combination of reflective and survivalist literature. The Day After’s Jason Robards, in various stages of radiation sickness, appears at the top of the page.

The anxious lead-up to the movie’s premiere offered fodder for conservatives looking to discredit nuclear fears as, essentially, unmanly. In the National Review, William F. Buckley, Jr. mockingly answered Question #8 in the discussion guide (“My greatest fear about the Nuclear Age is—”) by deploying the gender-loaded H-word: “That we will become so hysterical we will cease to see that the only way to avoid nuclear war is to cherish our nuclear arsenal.” Buckley had his own fears—that America would fall under the thumb of the repressive Communists. These, of course, he saw as rational.

Other conservatives, agreeing with Buckley, made some concrete attempts to undermine the movie’s success. Phyllis Schlafly protested the movie (“a two-hour political editorial”) by writing to ABC affiliates. Douglas O. Lee, chairman of Americans for Nuclear Energy, Inc., sent a letter to execs of Fortune 500 companies, calling The Day After “highly emotional propaganda for the antinuclear movement in this nation,” and asking the executives to avoid advertising on ABC during the broadcast.

The movie itself is—forgive me!—boring. Much more terrifying and unrelenting televisual apocalyptic narratives have been available before and since. A viewing is enough to convince me that The Day After’s potency was in its ubiquity.

The opening credit sequence, whose soundtrack and point of view was inspired by Pare Lorenz’s 1938 documentary The River, sweeps over the Kansas landscape, taking in baseball diamonds, harvesters, trains, and a beautiful frolicking horse. Children figure prominently: in school, with their families, riding bikes.

Credit sequence from The Day After.

The first half introduces characters living in and around Lawrence, Kansas, whose days march on in a fog of routine represented as typical American life. College students, surgeons, nurses, kids, parents, soldiers are all oblivious to the impending doom.

The film is split in two by the bombing sequence, which uses X-ray effects to show the destruction wrought on individual humans. “ABC trimmed back the destruction scenes during the final edit of the film late last summer,” Glenn Collins reported in the Times. “Originally there were more shots of people being vaporized during the initial blast, including a mother and her baby standing by a window in the child’s room … Network executives were petrified in the final days before broadcast.”

Bombing sequence from The Day After

The movie was originally supposed to be twice as long, with three-fourths of it taking place after the bombs drop, depicting the violence, disease, and hunger of a post-nuclear landscape. (That was much the shape of the documentary-style BBC series Threads, a much grimmer narrative aired in 1984.)

In the “aftermath” portion of the film, although there are paralyzing scenes of hospitals full of casualties, there are also moments of human connection: a soldier helps a mute refugee; the doctors at the hospital work until they drop; a baby is born. In this clip, Steve Guttenberg (then credited as “Steven Guttenberg”), playing a college student, reconnects with a girl he met after the blast. Their mutual baldness and sickness becomes a point of sympathy, bringing them together despite the awful situation.

Effects of radiation from The Day After.

In the end, despite reaching such an astronomical percentage of American households, the program made surprisingly little money for ABC. The 30-second ads sold during the broadcast went for cheaper than usual, because of the whiff of controversy, and the network purposely didn’t try to sell any commercial time during the 90-minute-long “Viewpoint” discussion that followed the movie. Revenues from foreign broadcasts (the film was shown in Germany, Japan, Switzerland, the UK) bumped up the network’s profits.

The “Viewpoint” discussion, anchored by Ted Koppel and conducted in front of a live studio audience, revealed a strict division between the conservative and government voices (Buckley, Jr., Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, Brent Scowcroft, and Robert McNamara) and the representatives of liberal humanism (Carl Sagan and Elie Wiesel).

Sagan spoke of the unknown dangers of nuclear winter, and Wiesel eloquently reminded the audience of the danger of concentrating such crushing power in the hands of a few (“I am afraid of madness,” he said). But whenever Koppel, or an audience member, brought up the issue of fear or emotion, the first group turned to dry policy discussions, or denied the very idea of an emotional reaction.

Kissinger, for one, dismissed the movie as “indulging in an orgy” of provocative depictions. He said: “We can’t scare ourselves to death. If the Soviet Union gets the idea that the US has psychologically disarmed itself, the precise consequences we describe here will happen.”

Kid fears came up more than once. A teacher in the audience asked the panel about how to talk to his students about their worries, saying (with echoes of Lifton’s theory of psychic numbing) that he worried that they were irretrievably cynical. Robert McNamara replied, in a seeming fit of pique, calling for confidence in speaking with young people:

McNamara’s reply on “Viewpoint”.

McNamara’s reaction seemed to blame scared parents and teachers for children’s fears, seeing the dynamic as the product of poor communication on the part of quavering adults, not as a result of the nuclear geopolitics.

What were the actual effects of The Day After, and of the nuclear fears of the early ‘80s, on kids? The media gathered anecdotes (“My opinion now is that the movie was just a flop in our school,” said 12- year-old Matt Goldman, a seventh grader in Evanston, Ill. “A few days afterwards, no one really talked about it again. We dropped it”) and the scientific and medical communities carried out selected studies.

Dr. Thomas Boll, who surveyed health facilities looking for referrals related to the film, told the New York Times that they found no effect. “The cautions were gratuitous and over-exaggerated,” he said. Yale’s Dorothy Singer, who had publicly warned of the effects of the movie, pled an interference effect: “I had a sense that if we’d done nothing, if we hadn’t warned parents, then there would have been many more problems than we had. We know that many parents forbade their kids to watch, or watched with them.”

Surveys conducted among students who had seen the film found that effects were variable, and not necessarily tending toward activism. Psychologist Richard L. Zweigenhaft, who interviewed high school students and college freshmen in 1982 and 1984, wrote of his findings in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: “A year after ‘The Day After,’ students were more likely to know certain things about nuclear weapons than they were two years earlier but showed no evidence of knowing more about the political context in which nuclear weapons exist; in fact, they showed some evidence of knowing less.”

Zweigenhaft saw these consequences as drastic, and negative:

The combination of greater knowledge about the destructiveness of nuclear weapons and woefully inadequate knowledge about the historical and political context in which they exist indicates that students now are receptive to emotional rather than rational approaches to this issue. These students are particularly likely to accept uncritically such dreamy concepts as Reagan’s “Star Wars” proposal. Perhaps this helps explain why the nation’s youngest voters voted overwhelmingly for Reagan.

And Robert Coles, interviewing children for his books The Moral Lives of Children and The Political Lives of Children, found very little nuclear fear at all. Coles critiqued much of the existing research, arguing that samples had been skewed toward the wealthy and those whose parents were already involved with anti-nuclear activism.

The controversy within the psychiatric community provided fodder for conservatives looking to discredit the use of kids’ fears as political capital. Writing in Commentary in 1985, Joseph Adelson and Chester E. Finn, Jr. leaned on Coles’ findings heavily. Adelson and Finn accused psychiatrists (including Lifton) who brought children in to testify to Congress of turning kids into “hostages to ideology,” and of greatly exaggerating the incidence of their fears.

More than that, though, the two simply didn’t believe that adults should look to children’s feelings in making policy decisions. “That we can attain truth more easily through innocence than through intelligence,” they write, “is a notion too sentimental to withstand scrutiny … To accept the childlike as testimony or as argument requires a suspension of disbelief.”

Today, activists working on the issue of climate change often invoke children: their futures, their fears. Part of the problem with discussions of climate science is scale: change is occurring over a span of time and space that’s hard to connect with, intellectually and emotionally. Children, as many activists point out, will be alive to bear the brunt of the changes, which they did not cause. Kids’ emotions about this fact are now political. The connection between the historical fears of nuclear bombing and the present-day anxiety over climate is often explicitly drawn (a Washington Post reporter working on a 2007 story about climate change anxieties interviewed a therapist who said “Kids used to have fears of war and nuclear annihilation. That’s dissipated and been replaced by global warming”).

Conservative opposition to the presence of these fears in public discourse has also carried over into the climate debate. The concepts of captivity, indoctrination, and impressionability that Finn and Adelson identify are now forefront in conservative criticisms of activist climate change curricula. Bjorn Lomborg complained in The Guardian that “the continuous presentation of scary stories about global warming in the popular media makes us unnecessarily frightened. Even worse, it terrifies our kids.” Recounting a conversation that he had with “a group of Danish teenagers,” Lomborg claimed that one “worried that global warming would cause the planet to ‘explode.’” Lomborg emphasized that “this scare was intended,” arguing, much like Finn and Adelson had, that adults were purposefully, and unnecessarily, terrifying children.

In 2013, the National Research Council, National Science Teachers Association, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science released a new set of non-binding standards that advanced the importance of climate change education to elementary school, and advocated for interdisciplinary approaches to teaching the subject. Blogger The Lonely Conservative, a mom named Karen (identified only by her first name), warned, “The climate alarmists are going to have a new captive audience.” Confrontations between parent and the child would be forthcoming, Karen advised: “Add Climate Depot [a denialist site] to your browser bookmarks so you can be armed with the truth when your children come home and tell you what they learned in school about climate change.”

Denier “JS,” who pseudonymously blogs for the site Climate Lessons, has compiled a massive list of international examples, as reported in the media, of children’s climate fears. In JS’s cosmology, innocent children’s mental states are threatened by climate “alarmists’” overreach, and long-suffering parents are left to pick up the pieces.

There seems to be a fundamental disconnect between conservative and liberal-activist beliefs about the place of childhood in the public sphere. While activists present children’s feelings as crushing, final evidence of the awfulness of a problem, conservatives raise several levels of doubt: first, that the phenomenon prompting these fears is as bad as claimed; second, that kids even feel as badly as activists say they do; third, that such feelings are “natural,” rather than stoked up by liberal agitation in the form of media and curricula. This idea that children are the truth-tellers, closer to the marrow of human experience, is part of a sentimental Romanticism that conservative onlookers decry, arguing that we can’t conduct national policy based on the anxieties of children.

For both sides, children’s fears stand in as a proxy for all of our emotional responses around issues of apocalyptic risk: our “hysterias,” nightmares, and forebodings. The idea that conservative ideology is free from such responses is part of a self-presentation deeply rooted in ideals of rational masculinity. Kids are afraid; moms are afraid; therapists make soothing noises; men know the truth of the risks, see the real possible futures, and act accordingly.